The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given the Tactical Notebook permission to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. Other parts of this books may be found with the help of the following guides:

In 1919, while all these legislative maneuverings were in progress, the War Department asked General Pershing to examine the records of the AEF and to draw whatever lessons might be appropriate for the future. To perform the necessary studies and at the suggestion of his staff, Pershing appointed a number of review boards, all presided over by a “Superior Board” which would render the final report. In addition to charging the Superior Board with carrying out the War Department’s request, Pershing also ordered it to explore the tactical and structural implications of the AEF’s experience.

The Superior Board was very harsh in judging the Army’s wartime performance. Special criticism was leveled at the performance of the combat arms and, in particular, at the disastrous policy of filling the infantry with ill trained and marginally intelligent recruits. However, apart from these matters and a War Department request that it review its own functions, the Superior Board focused most of its efforts on how to organize the postwar infantry division.[1]

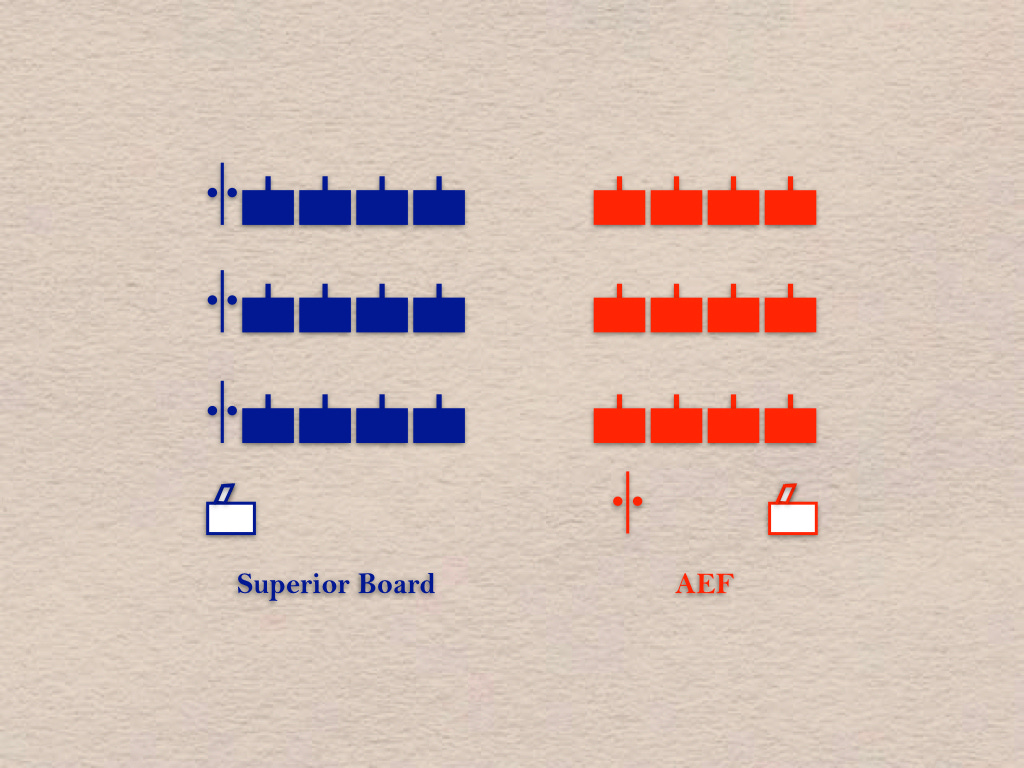

Of the eight officers composing the Superior Board, four had commanded AEF divisions or larger units, one had been a United States observer of the German Army until April 1915, and most had held important staff positions. All had been heavily involved in organizational issues. For its evaluation of infantry organization an Infantry Board and a Machinegun Board assisted the Superior board. The sum of their efforts was a recommendation that the post-war infantry division have the same basic “square” structure as the AEF’s 28,077-man 1918 division. At 29,200 officers and men the Superior Board’s division was even larger.

The Superior Board retained most components of the AEF division in substantially their original form but it did recast the infantry. The Infantry Board had recommended retaining the old organization of four rifle companies per battalion plus a machinegun company per regiment and a machinegun battalion per brigade but the Superior Board overruled it. Instead, the Superior Boarded opted to add a fifth (machinegun) company to each infantry battalion and to eliminate the brigade machinegun battalions and regimental machinegun companies. The motorized divisional machinegun battalion would remain.

In lieu of its machine gun company, each infantry regiment would get a howitzer company. This unit was a combination of the old sapper-bomber and one-pounder gun platoons of the AEF infantry regimental headquarters company. Each of its three platoons would have one M1916 37mm infantry gun (the U.S. version of the French Puteaux gun) and two 3-inch Stokes mortars. One platoon could be attached to each infantry battalion, if required. Each platoon’s task was to fire high explosive shells against enemy strongpoints that the artillery had missed. The gun would attack vertically faced targets (such as redoubts or pillboxes) while the mortars attacked horizontal targets (like entrenchments or foxholes). The Superior Board was satisfied with the 37mm gun but considered the mortar’s range and accuracy to be very inadequate and recommended that it be replaced as soon as possible. Ideally, its replacement should be a small howitzer that was readily portable and might, if its flat trajectory performance were good enough, replace the gun as well as the mortar. The howitzer company was so named in anticipation of the procurement of this weapon.[2]

The Board’s other major changes mainly affected the staffs controlling infantry units. The Board concluded that while most AEF staffs suffered from a lack of experienced officers, those at division level and above were generally adequate in terms of their size but lower level staffs, especially those controlling regiments or battalions, were entirely too small. The reader will recall, that a major, assisted by a lieutenant (serving as adjutant), commanded an AEF battalion. The battalion’s parent regiment would supply a sergeant major, a mail clerk, and a total of ten messengers and signalers from its headquarters company and would also furnish sections from its medical detachment and supply company. The signal battalion from the parent division would provide a telephone detail. By August 1918, each battalion also had a lieutenant to serve as intelligence officer and would get another lieutenant from its parent regimental supply company to serve as supply officer.

By French or German standards all of these attached personnel provided ample staffing. In a French infantry battalion a major (or captain) was in charge. His only staff officers were two lieutenants, who acted as adjutant and intelligence officer, respectively, and there was also a surgeon. Enlisted support came from a battalion headquarters platoon under a senior sergeant. Most of the battalion’s service support, as in the AEF, came from a regimental supply company. A German battalion headquarters had a captain or major (often a lieutenant) as battalion commander, assisted by an adjutant, a paymaster (a warrant officer equivalent clerk), and a surgeon. Sometimes there was an extra lieutenant to act as supply officer.

By contrast, the command element of a British battalion was at least three times larger. A lieutenant colonel was in command and he had a major as his executive officer plus eight other officers and an attached chaplain. [3]Enlisted support came from a company-sized “headquarters wing” of about 150 men who operated staff, administration, transportation, signal, and medical sections.[4]

The AEF staffs had failed not because they were too small but because they lacked competent officers. Failure would have been most obvious at the battalion level where the staffs were smallest and where the skills required were those for which they were least likely to have been trained. For most of the junior AEF infantry officers, training had focused on making them acceptable platoon leaders who might eventually become passable company commanders. It was an operating assumption that either they would be dead or disabled or the war would be over before they could rise much higher. Hence, further growth potential was not contemplated.

By contrast, the German and French systems usually started out with men who already had a year’s enlisted experience or who had been officer cadets and were already familiar with basic soldier skills and even with squad/platoon tactics. Though they would only graduate as lieutenants, their training began in earnest with a study of the battalion and then worked upward and downward. This method produced officers who were not only well qualified for platoon or company command but also could assume higher responsibilities.

The French and Germans needed fewer officers because they had proficient ones. Because they needed fewer officers, more care could be taken over the training and selection of the officers they had, thus making them better still. The NCO corps got stronger as well because fewer officers competed with it for responsibilities. Skillful officers also meant smaller staffs since each officer could be more efficient. Smaller staffs enjoyed a significant tactical advantage in their ability to operate faster than large ones.[5]

Despite the obvious advantages of the Franco-German system of selecting and training officers, the Superior Board concluded that such a model was not appropriate to an American style citizen army. (This was despite the high content of reservists in both the French and German officer corps.) Instead, the Board made an exception to the usual American practice of imitating the French and opted for the British practice of commissioning more officers with (individually) fewer skills. However, the Superior Board strongly endorsed a new French-designed staff system. The AEF had already adopted it at army level and above and, by the end of the war, was extending it to corps and divisions.

Originally, the new system divided the staff into five sections of which the first was the adjutant’s section for personnel administration, the second was for intelligence, the third was for plans and operations, the fourth was for logistics, and the fifth was for training. Each section was (at least in theory) equal to the others and had direct access to the commander through the chief of staff. In 1918-19, the training and the plans and operations sections were combined, thus reducing the total number of sections to four. The Superior Board recommended the extension of this system to the regimental and battalion levels even though the French considered it far too unwieldy for use below the division level. However, the War Department ultimately adopted the Superior Board’s recommendation and U.S. military staffs at all levels have retained this basic structure ever since.

Editor’s Note: The format of the many appendices to this work fit poorly with Substack. For that reason, I have placed them on a PDF file that can be found at Military Learning Library, a website that I maintain.

For Further Reading:

[1] John B. Wilson, “Mobility Versus Firepower, The Post World War I Infantry Division” Parameters September 1983 p. 47; “Extracts from the Report of the Infantry Board, AEF, On Organization and Tactics” (one of 160 copies of an unpublished manuscript reprinted for the General Staff College 1919-20).

[2] “Extracts from the Infantry Board” op cit pp. 9-12, 20, & 23-25; “Infantry Organization” staff article from Infantry Journal, June 1920 (Washington DC, US Infantry Association) pp. 1029-33; and Maj A. W. Lane, General Staff “Tables of Organization” pp. 486-487.

[3] These other officers included an adjutant and a medical officer (usually captains), as well as a transport officer, a machinegun officer, a quartermaster, a signals officer, and two liaison officers (all lieutenants). Typically, only about seven or eight of these officers were actually present with the battalion at any one time. The signals and liaison officers were most likely to be absent.

[4] A good review of the composition of a typical British battalion headquarters can be found in Rudyard Kipling, The Irish Guards in the Great War, the First Battalion (reprinted New York, Sarpedon Publishers 1997; originally published 1923); see also M. A. Ramsay, Command and Cohesion, op cit. German organization comes from a personal interview with Mr. Bruce Gudmundsson; see also Inventaire Sommaire des Archives de la Guerre, Série N 1872-1919 Introduction: Organisation de L’Armee Française op cit.

[5] Personal interview with Bruce Gudmundsson op cit.