“At some time in the future it is probable that all division artillery will be motorized. The result of such change in the prime mover would be to remove the present restriction as to weight of gun and carriage. The board senses a demand in the near future for a light field gun having a maximum range of approximately 15,000 yards [13,700 meters]; such range may be achieved by increasing the muzzle velocity and, perhaps, the weight of the projectile, although change in the form of projectiles will give some improvement over the present ranges.”

Report of the Westervelt Board (11 January 1919)1

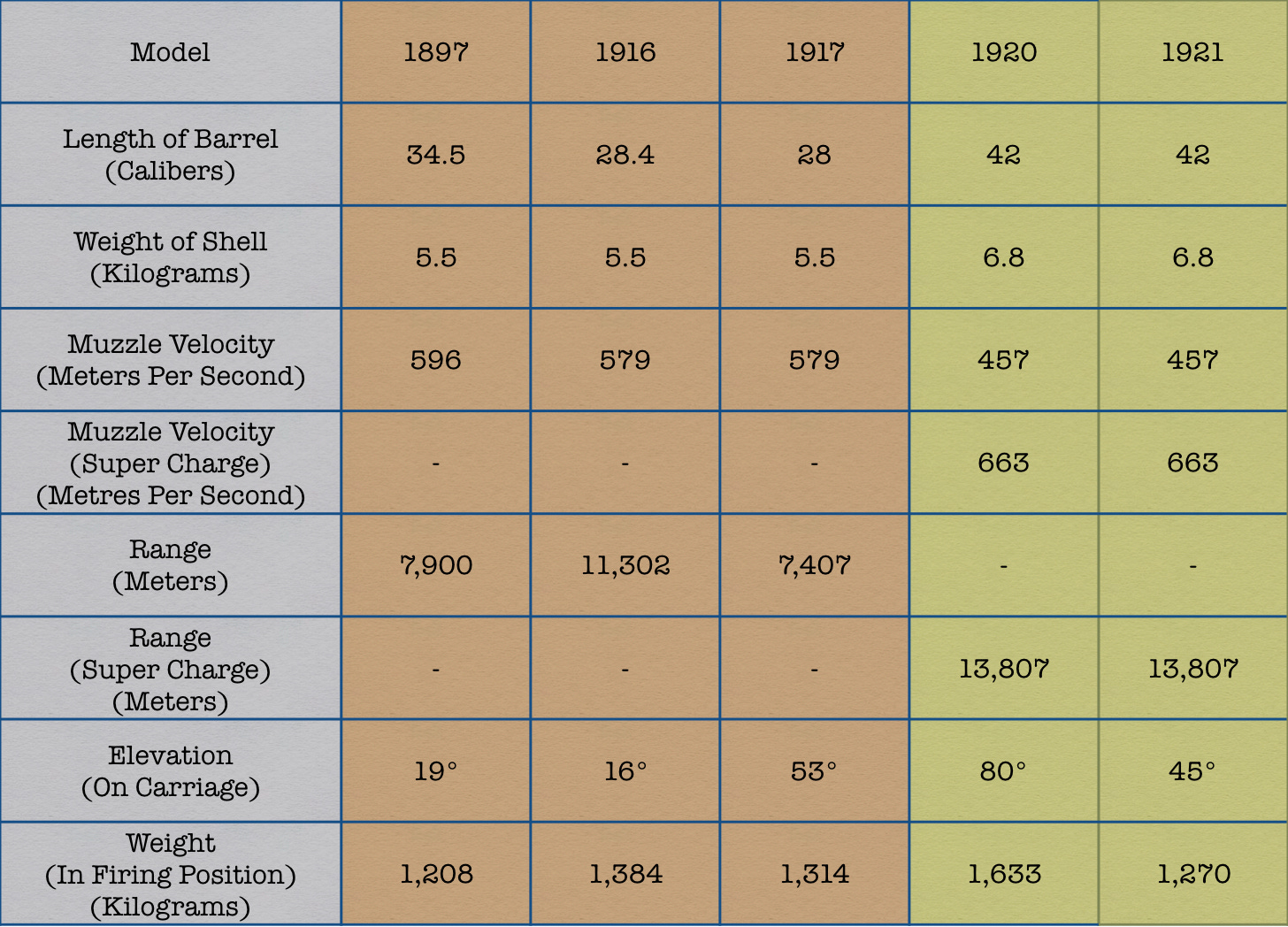

In 1919, as some officers of the Ordnance Department worked on the selection of a standard 75mm field gun for the peacetime US Army, others devoted their attention to the design of an alternative to those weapons, all of which had been designed to be pulled by teams of horses. The latter field piece, known as the 75mm field gun (Model 1920), used a barrel that was much longer than those of hippomobile field guns to permit the use of larger propellant charges, thereby bestowing greater speed upon somewhat larger shells.2

All other things being equal, the combination of larger charges, bigger shells, and greater speed translated to greater range. Further increase in the distance a shell fired from a Model 1920 field gun resulted from the ability of its carriage to raise its barrel to an angle of 45 degrees. (The carriage permitted elevations up to 80 degrees. However, the greatest ranges were achieved when the barrel was raised to 45 degrees.)

The designers of the Model 1920 field piece assumed that only ten percent or so of the targets it fired upon would be located at extreme ranges. They therefore provided the gun with two types of charges: an ordinary charge for shooting at targets within 11,000 meters or so and a “super’ charge for long-distance work. In doing this, they provided the piece with the capability to reach distant targets while reducing the expenditure of propellant, wear-and-tear on the barrel, and stress on the recoil system.

The ability of the Model 1920 field gun to fire at angles between 46 degrees and 80 degrees allowed the weapon to be used against balloons. It also permitted the “dropping” of shells on top of targets in the manner of a mortar. These benefits, however, came at the cost of a great deal of weight.

The next 75mm cannon to emerge from the workshops of the Ordnance Department solved this problem by mounting the barrel of the Model 1920 upon a much lighter carriage. The resulting weapon, called the Model 1921, gave up the ability to raise its barrel above 45 degrees in order to achieve a weight reduction of 363 kilograms (800 pounds.)

As they were meant to be towed by motor vehicles, both the Model 1920 and Model 1921 field guns sported steel wheels, reinforced axles, and rubber tires

A typescript copy of report of the Westervelt Board can be found at the Morris Swett Library at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The complete report of the Westervelt Board can be found at the Morris Swett Library at Fort Sill, Oklahoma and (under the title of Study of the Armament and Types of Artillery Matériel to be Assigned to a Field Army) in the issue of Field Artillery Journal for July-August 1919.

At 42 calibers, the barrel of the Model 1920 field gun was nearly a quarter longer than that of the Model 1897 (“French 75”) and half again as long as the barrel of the Model 1917 (“British 75.”)

“hippomobile” that is a new one 😁