A Division in the Defense (Part II)

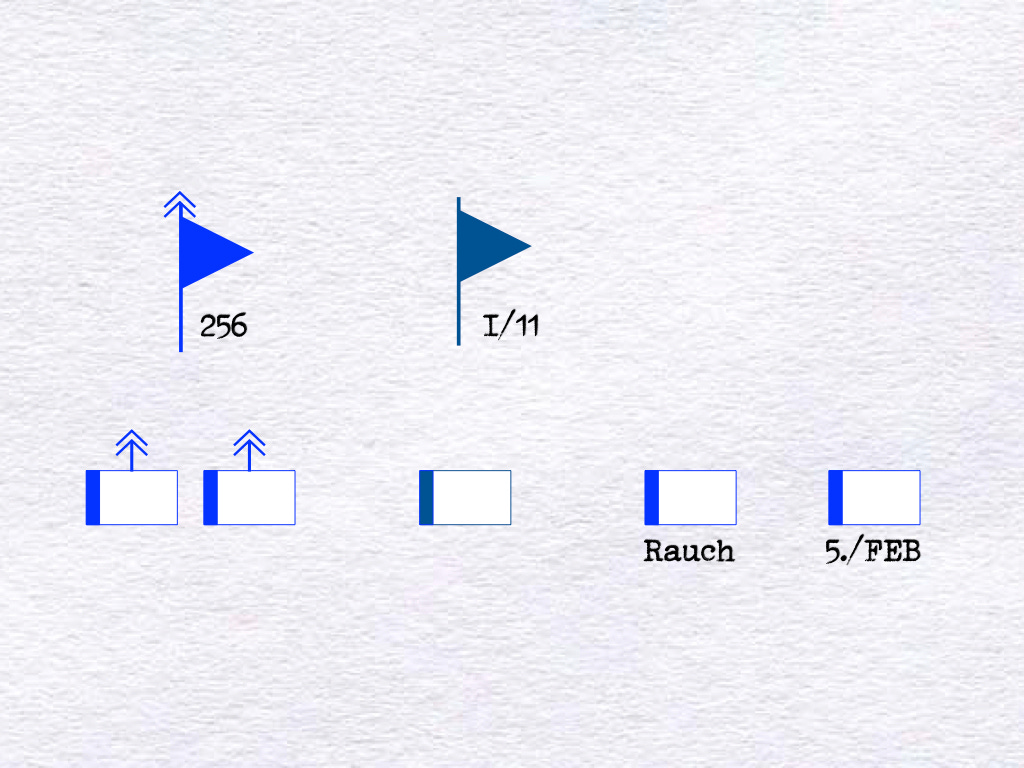

Depicted with tactical symbols, the reserve under the direct control of the commanding general of the 256th Infantry Division looks weak enough. However, it is only when heads and weapons are counted, however, the true weakness of this tiny force can be seen.

With two line companies and the remnants of a battalion headquarters, the divisional pionier (combat engineer) battalion could muster a hundred men. (The third company of this battalion had been attached to one of the infantry regiments of the division.) The First Battalion of the 11th Grenadier Regiment (which had been provided by another division) was even weaker. It possessed a grand total of sixty-eight men. Thus, the two battalions of the division reserve had fewer soldiers than a full-strength infantry company.

Partial compensation for the absence of a suitable number of soldiers came in the form of heavy weapons. The two battalions wielded a total of six 81mm mortars, five tripod-mounted machine guns, sixteen light machine guns, and four portable flamethrowers.

If the two understrength battalions of the division reserve provided all of these heavy weapons with crews, there would have been few, if any, men left over to serve as riflemen. Thus, while the division reserve could pour a great deal of fire into a Soviet force making a frontal attack, it was poorly suited to the task of conducting counterattacks. This, in turn, meant that the division reserve served chiefly as a means of filling gaps in the front line.

The fifth company of the division’s training and replacement unit (Feldersatzbataillon) had more men than the First Battalion of the 11th Grenadier Regiment. These seventy-nine men, all of whom were either partially trained or recovering from wounds, wielded six light machine guns.

“Battlegroup Rauch” (Kampfgruppe Rauch) consisted of thirty-five men, none of whom carried anything heavier than a rifle. (The grandiloquent moniker of this tiny task force reflects the same wave of linguistic inflation that turned “assault gun battalions” into “assault gun brigades” and appended the prefix Sturm- to an incredibly wide variety of words.)

As marching from one end to the other of the sector held by the 256th Division was a good day’s work, it is unlikely that the commanding general kept his reserve in one place. Rather, he may have used it to occupy fall-back positions, places where the remnants of shattered front line units might rally. Alternatively, the division commander may have parceled out the elements of his reserve to regiments at the front, with the proviso that they only be employed with his express permission. Finally, the chief task of the division reserve may have had less to do with defensive dispositions of the division than of the need to give units a chance to rest, reconstitute, and recover from the stress of front-line service.

Source: Barbara Selz Das Grüne Regiment. Der Weg der 256. Infanterie-Division aus der Sicht des Regiments 481 (Freiburg im Breisgau: Verlag Otto Kehrer, 1970)

Ukraine is in this situation now and for some time.