18th Artillery Division (III)

Armies of the Second World War

On 13 November 1943, the commanding general of the 18th Artillery Division issued an order specifying that, when choosing positions for their batteries and battalions, leaders should make anti-tank defense their first priority. Thus, even if doing so reduced their ability to employ indirect fire against targets of other sorts, they should locate their guns in ways that optimized their ability to shoot at enemy armored fighting vehicles.

According to the order, effective antitank work depended upon large fields of fire. Thus, artillery pieces should deployed in ways that allowed them to begin engaging hostile tanks with direct fire when the latter came within 800 meters or so. (The order set the minimum depth of anti-tank fields of fire at 500 meters.)

This “start firing when tanks are half-a-mile away” rule differed considerably from the way that soldiers armed with purpose-built anti-tank guns had plied their trade for the past twenty years. Knowing that the effectiveness of the shells that they fired depended upon the speed with which they flew, and that velocity diminished with distance, the full-time tank hunters tried to get as close as they could to their quarry before opening fire.

The shells that the field pieces of the 18th Artillery Division depended chiefly upon explosions to inflict damage upon tanks. (Some of these were explosions of the ordinary kind. Others, produced by special anti-tank shells, were of types designed to burn holes in steel.) Thus, any price paid for the loss of velocity in the course of flight paled in comparison to the advantage of additional opportunities for such things as the engagement of multiple targets, the delivery of coups de grâce to disabled tanks, and the shelling of men on foot, whether tank riders or dismounted crewmen, keeping company with enemy armored fighting vehicles.

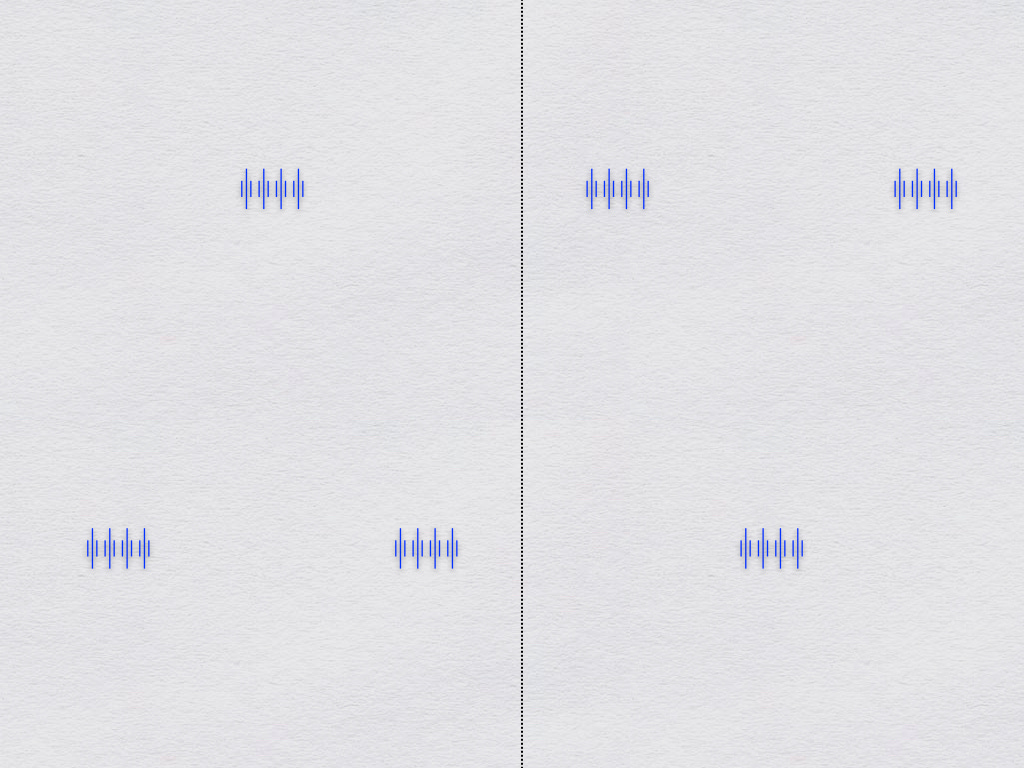

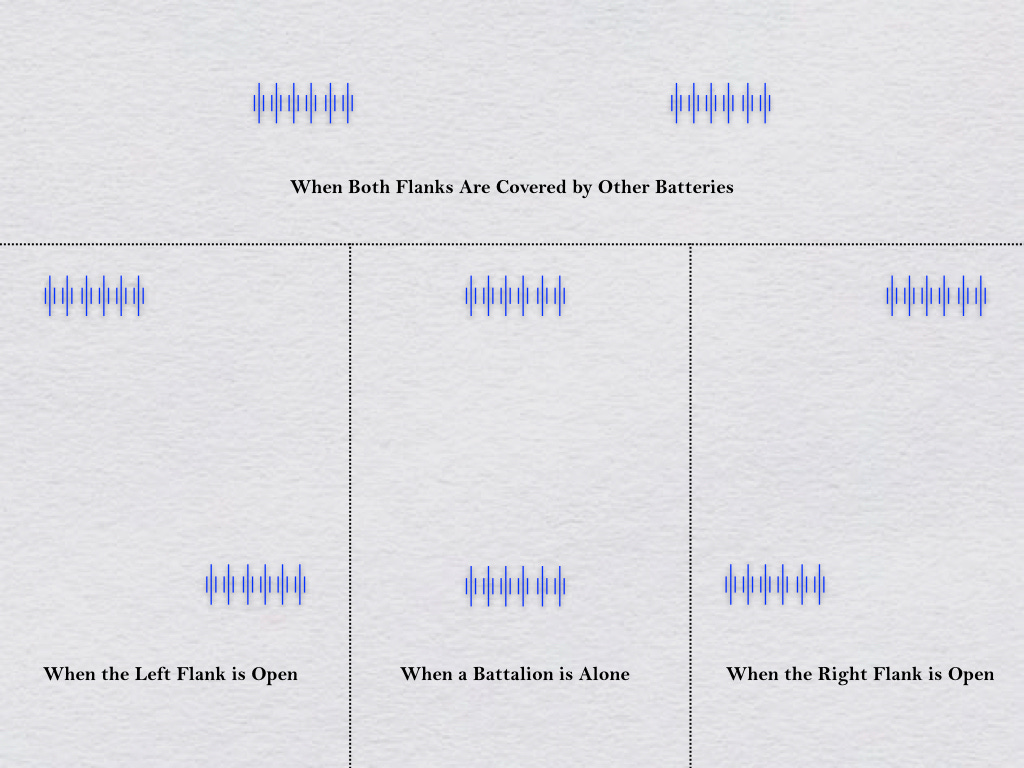

The order that proclaimed the primacy of anti-tank defense also described six options for the deployment of the component batteries of a battalion. Two of these templates placed each of the three four-piece batteries of a triangular battalion at the corner of a wedge. The other four formations arrayed the two six-piece batteries of binary battalions in ways designed to mitigate particular vulnerabilities.

The common element in all of these formations was mutual support at comparatively long ranges. That is to say, an enemy tank unit trying to overrun one battery would find itself subject to fire from another battery 800 to 1,000 meters away. This ensured that the tanks could not start a short range battle (where they enjoyed many advantages) without first fighting a long range battle (where they were at a serious disadvantage).

All formations but one, moreover, ensured that the rear of each battery was covered by the long range fire of another. (The one exception was the formation, depicted in the center of the second diagram, for two-battery battalions that had no neighbors on either side.)

The formations adopted by the battalions of the 18th Artillery Division converted the entire depth of the division position into a trap for any Soviet forces that happened to break through. Because of this, the commanding general ordered battalion and battery commanders to reorient and, in some cases, reposition, their observation posts. In particular, each firing unit had to be able to make use of observation posts that permitted observed fire within the division's position as well as forward of it.

The anti-tank formations for the battalions of the 18th Artillery Division were not without disadvantages. In particular, they made it easier for Soviet intelligence officers who had discovered the location of one battery to predict the likely location of the other battery (or batteries) in the battalion. This was especially true when a German battalion commander placed his batteries in villages.

Sources: Wolfgang Paul, Geschichte der 18. Panzer Division 1940-1943 mit Geschichte der 18. Artillerie-Division 1943-1944, (Reutlingen: Preußischer Militär-Verlag, 1989), pages 288-291 and documents of the 18th Artillery Division on file at the U.S. National Archives, Captured German Records, Microfilm Series T-315, Roll 704