Which Seventy-Five? (Author's Solution)

Ordnance Decision Game

This post provides the author’s solution to a decision game. If you have yet to play this game, please refrain from reading until you have read the post that lays out the problem.

As I have yet to uncover the right sort of memoirs or memoranda, I know little about the details of the decision made by Clarence Charles Williams. I find it hard to imagine that Major General Williams played no role in the decision by Peyton March to designate a particular model of 75mm field gun as the Army’s standard weapon of that type. Nonetheless, I have yet to encounter any evidence that allows me to characterize either his opinion on the matter or his influence with General March. As a result, all but the last paragraph of this solution falls into the category of “informed speculation.”

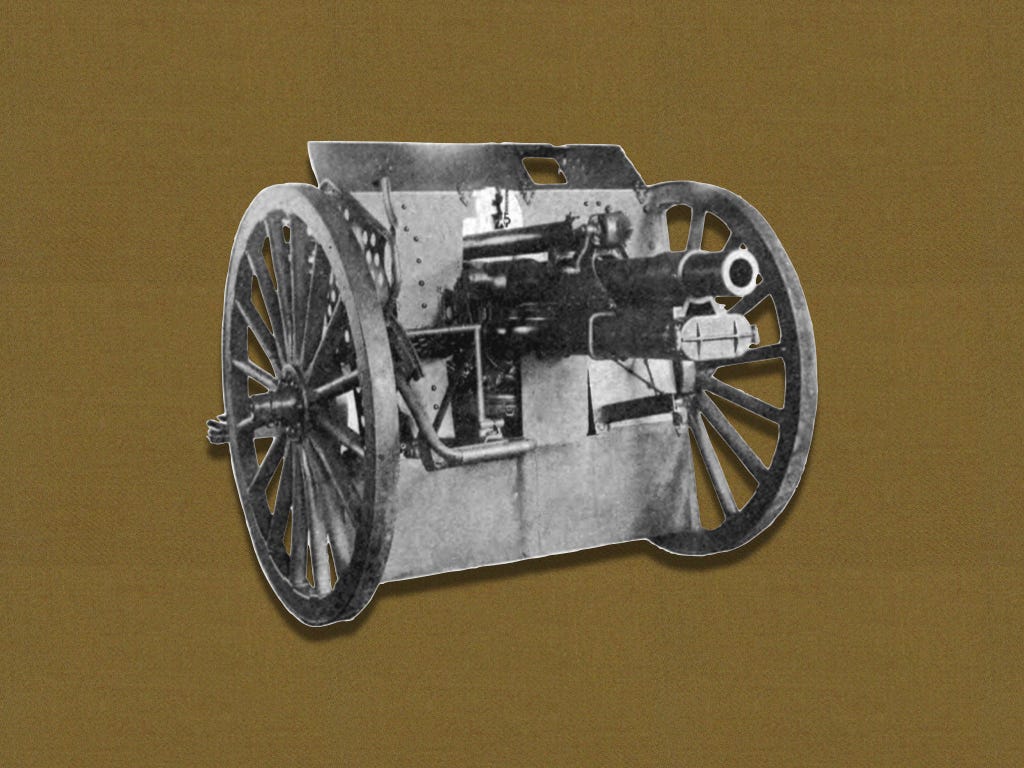

The British seventy-five offered no advantages over either of the other two guns in question. Moreover, it was heavier than a weapon with its capabilities had to be and had been built entirely by a single private company.

The extra weight of the American seventy-five had been the price that its designers paid for the advantages of a split trail. That of the British seventy-five, however, resulted from the use of components that had been designed to support the heavier barrel of the original eighteen-pounder field gun. Indeed, despite the use of somewhat lighter barrel, the British seventy five (1,314 kilograms) weighed almost as much as its immediate ancestor (1,320 kilograms).

In the early twentieth century, American ordnance officers preferred to build weapons in government arsenals, so much so that only resorted to the use of private companies to do such work in emergencies. Thus, the fact that all of the expertise and tooling used to built the British seventy-five belonged to Bethlehem Steel would have deprived that weapon of any residual attraction that it may have possessed.

The American seventy-five enjoyed a number of advantages. Based on the 3-inch field gun of 1916, it was the most modern of the three pieces. (The French seventy-five dated from 1897, the eighteen-pounder from 1903.) It could send its shells much further than projectiles fired by either of its competitors. Moreover, it was a home-grown product that had been made in a variety of workshops, both government and private.

If the problem faced by Major General Williams was entirely a matter of picking the best gun, then he probably would have selected the American seventy-five. The task at hand, however, was only partially a matter of technical characteristics. Both he and General March were obliged to consider the number of each type of weapon in possession of the War Department, as well as such things as stocks of spare parts and accessories.

Neither Williams nor March knew how many field guns would be needed to equip the field batteries of the peacetime military forces of the United States (whether Army, National Guard, or Marine Corps.) Thus, were numbers were concerned, both were inclined to err on the side of caution. Moreover, the experience of the World War had convinced them of the need to keep weapons on hand for any short-fuzed expansion that might take place.

Thus, our protagonist opted for the French seventy-five. Almost immediately, however, he assembled two teams of engineers, one to design a split-trail carriage for the French seventy-five and one to build, from the ground up, the prototype of a second American 75.

Okay, I can see why the French gun was selected. After all, it was only fired once, then left behind when the French forces ran to surrender. (Sorry, couldn't help it...)