Tricky Terms of Art

From the American Civil War

Nearly all the records of all of the parties to to the American Civil War were written in varieties of English that twenty-first century Anglophones find easy to read. Nonetheless, several important terms of art from the American military lexicon of the 1860s bore meanings at odds with their present-day definitions. This was particularly true for words that described the categories, whether administrative or tactical, to which various units belonged.

In both the United States of America and the Confederate States of America, the "militia" was a local military organization composed of part-time soldiers who had enlisted in the service of a particular state. That is to say, the highest official in a militiaman's chain of command was the governor of his state.

Prior to the war, militia units often had a highly social character, with units organized by social class and ethnic group, and as much time devoted to parades and celebrations as actual military training. At the same time, in an era where few local governments had anything that resembled a police department, militia units served as the first-line of defense against civil disorder, whether that be fights between urban gangs, industrial unrest, or slave revolts.

At the start of the Civil War, the federal governments of the United States created a new category of troops known as "United States Volunteers." These were full-time soldiers who belonged to units that, while formed by individual states, were to be paid, supplied, and regulated by the federal government. The central government of the Confederate States did much the same thing, accepting units raised by individual states into the service of the Confederacy as a whole.

There were many instances, in both the North and the South, where militia units transformed themselves into volunteer units, thereby retaining their interior organization, their uniforms, and their strong links to a particular locality. Indeed, the link between prewar militia units and wartime volunteer units was often so strong that the volunteer units preferred to be called by the names of their parent units rather than their official designations.

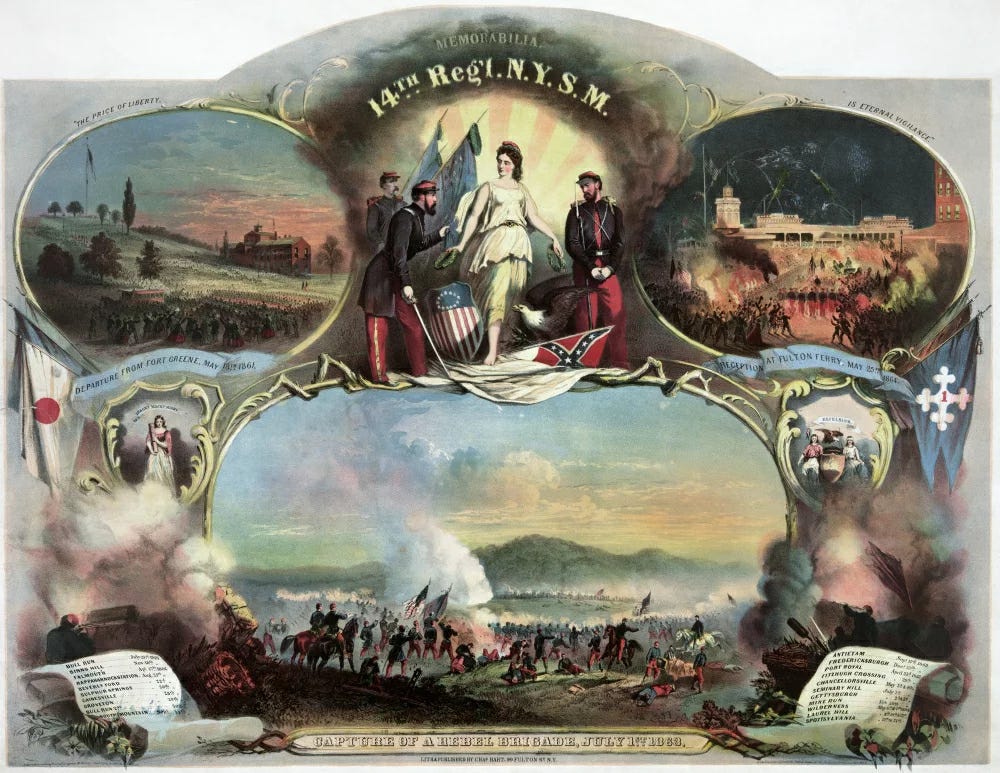

Thus, when the officers and men of the 14th Regiment, New York State Militia, enlisted en masse in the United States Volunteers, the unit became the 84th New York Regiment of the latter organization. As a rule, however, just about every person concerned continued to refer to the outfit as the “14th New York.” Moreover, despite the fact that the provision of clothing to United States Volunteers was a responsibility of the Federal government, the city of Brooklyn continued to pay for the non-standard uniforms worn by men of that outfit.

Other volunteer units, however, had little or no connection to the prewar militia. This was particularly true of units that were formed after 1861, as well as units formed in areas where the prewar militia movement had not been particularly active. Thus, for example, the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry, made famous by its defense of the Little Round Top during the battle of Gettysburg, had been raised ex nihilo in 1862 by enlisting men from all over the state.

As the volunteers marched off to war, the militia units of various states were reformed and revitalized. While still composed of part-time soldiers, these units were often mobilized to deal with local emergencies of various sorts. Indeed, as the war both exacerbated social tensions and made possible frequent outbreaks of lawlessness, wartime militia units were far busier than their antebellum counterparts had been. As a rule, however, militia units only took part in major operations when hostile armies moved through their home territories. Even then, they were often assigned to duties (such as the guarding of lines of communication) that kept them out of the orders-of-battle of armies.

To further complicate matters, some states raised organizations of a third type. Usually (but not invariably) known as "state volunteers", these were units of full-time soldiers that remained under state control. Whether employed in duties related to the war between the two federations of American states or those involving hostile Indian tribes, units of state volunteers were rarely employed beyond the borders of the states that created them. The great exception to this rule is provided by the units of the "Pennsylvania Reserves." While entirely funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, units of this organization served in much the same way as units of US Volunteers.

The term "reserve" usually referred to the place that a unit had in the order of battle of an army. Thus, in the (Union) Army of the Potomac of 1863, the "Reserve Brigade" of the Cavalry Corps was a brigade that, in contrast to all other cavalry brigades of that field army, was not part of a cavalry division. (Strange to say, all but one of the component cavalry regiments of the "Reserve Brigade" were units of the regular United States Army.)

Similarly, the "artillery reserve" was that part of the artillery of a large formation (such as an army or army corps) that had not been assigned to a subordinate formation (such as an army corps or division). In both cases, the term "reserve" indicated the units in question had been left "in reserve" when other units of the same type had been parceled out.

Once again, the exception to the rule is provided by the Pennsylvania Reserves. This organization got its name from the fact that its member units were left behind ("reserved") when the other units raised by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania were accepted into the service of the United States.