The Problem with Prediction

The War in Ukraine (2014-2023)

Recently, a minor mea culpa from Glenn Harlan Reynolds got me thinking about the problem of prediction. In particular, it sparked thoughts about the many predictions made about the ongoing war in Ukraine over the course of the past year or so, and how many turned out to be wrong.

“War,” as oft-quoted Carl once wrote, “is the realm of uncertainty.” Thus, we don’t know how things will turn out until after they have happened, the reports are written, the memoirs are published, and the archives have been opened. Even then, reasonable, well-informed, and well-meaning people may well differ about “how things really were.”

It is, of course, only fair to begin my critique of the prognosticators with the Present Possessor of the Perpendicular Pronoun. In the course of the crisis that preceded the invasion of 24 February 2022, I was sure that the painfully obvious troop movements were part of a purely diplomatic initiative. Mr. Putin, I believed, would be satisfied with the wedge he had begun to hammer into the heartwood of the Atlantic alliance.

Once the battalion tactical groups began to roll, however, I quickly learned my lesson. No more would I attempt to anticipate the actions, let alone uncover the intentions, of people who dwelt in far off lands. Instead, I resolved to do two things. First, I would ponder any mysteries that presented themselves, in the hope that, in reflecting upon things that didn’t seem to make sense I would somehow achieve a better sense of the whole. Second, I would pay more attention to things that change slowly, such as geography and the location of rail lines, waterways, and well-paved roads.

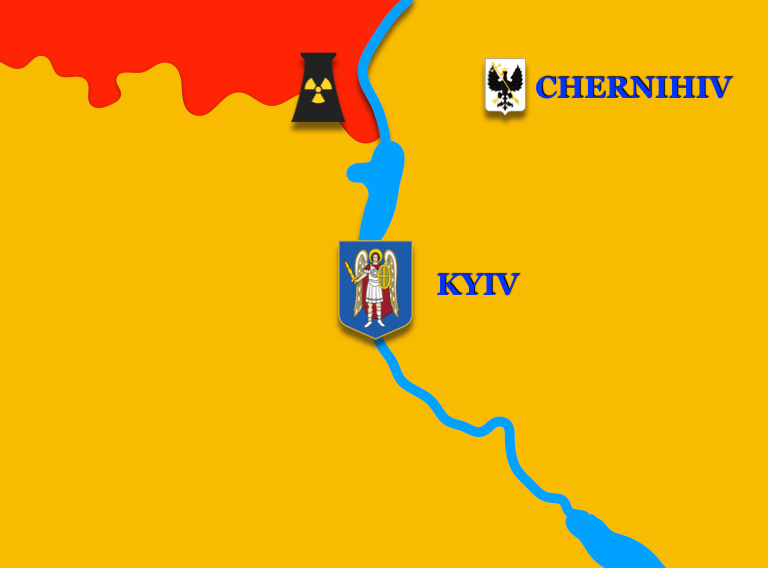

While I pondered the peculiarities of Ukrainian rivers, roads, and railways, the first great mystery presented itself. The Russian armored columns closest to Kyiv were moving along the west side of Dnipro River, south of the site of Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe of 1986. This meant that they would be traveling through terrain that was, at once, richly endowed with swamps and poorly provided with roads. It also meant that they would be separated, by an especially wide body of water, from any friendly forces operating east of Kyiv.

One solution to this conundrum draws upon an easy analogue. If the Russian invasion of Ukraine of 24 February 2023 was an attempt to replicate the German invasion of the Low Countries of 10 May 1940, then the bayou country northwest of Kyiv did for the battalion tactical groups what the Ardennes did for the motorized formations of Reinhardt, Rommel, and Guderian.

Alternatively, the Russians may have been motivated by a more recent analogy, that of the heavily forested slopes of northern Nagorno-Karabakh that sheltered Armenian soldiers from the drones flown by their Azerbaijani foes. History tells us that aircraft, whether manned or unmanned, did little to hinder the movement of Russian armored columns during the first few days of the invasion. Lacking the benefit of hindsight, however, the Russian wielders of grease pencils could not be so sure of the operational impotence of Ukrainian flying machines.

A third possibility concerns the need to link up with (and, as it turned out, rescue) the airborne forces that landed at the Antonov airport in the western suburbs of Kyiv. This, however, strikes me as a classic case of putting the tachanka before the horse. The point of delivering persons of the airborne persuasion to points in the path of armored columns, after all, is not an end in itself. Rather, if done properly, such descents should facilitate the operations of (necessarily more numerous) formations already on the ground.

The title of this piece promised a critique of foresight, and, in particular, of the many pundits who claim to possess it. Instead, Gentle Reader, I treated you to an explanation of my inability to make sense of an event that took place more than a year ago. Therefore, lest you judge me guilty of literary bait-and-switch, I offer a simple defense of the direction taken by this article. If a writer cannot properly predict the direction that his own handiwork will take, how can we expect him to anticipate the actions of men from faraway lands engaged in the most uncertain of human activities?

And other problem is that the Russian regime is opaque. It is likely dominated internally by fear and bureaucratic imperatives more than mission focus and operational rationality. The leaders all up and down the pyramid are probably being lied to by their subordinates, because their subordinates are corrupt and afraid of being caught being corrupt. Putin is a classic solo dictator who is surrounded by yes men who are afraid to tell him the truth. One strength of the old Soviet union was that it was a bureaucratic despotism rather than an individual despotism. As a result the bureaucracies chugged along, and there were numerous power centers, and there were even people with an interest in telling the truth, because they were more afraid to lie, because they were multiple sources generating information, and people who lied would get caught. It is a serious analytic mistake to think of Russia as it is now and the old Soviet Union as being analogous in terms of their internal operations. Different beasts. Further, the senior personnel in the Soviet Union, all the way to the end of the Cold War, were veterans of the Great Patriotic War. They took war seriously. They understood how to plan operations, and they inherited a system that was battle-tested and had proven itself effective. My guess is that not much remains of this old machine. In short, stupid decisions may not have some coherent inner rationale. They may be stupid decisions because the process generating them is significantly less effective than it needs to be.

There are pundits who make predictions to attract attention, but there are also professionals who make predictions because they want to test their models against reality. When I wrote "Plans Are Predictions", my view of prediction shifted from "it's a fool's game" to "this is something we have to do in war so we should try to be good at it." The difference between a pundit and a professional then comes down to intent and accountability. Pundits are unaccountable and will say whatever they want to advance their interests. A professional says "here is what I think will happen, here is why, and if I am wrong then I will update my priors." That is the message I got from this post.