The most remarkable thing about modern weapons is not their destructiveness. Rather, it is the ability of human beings to counter-act their effects. A slight irregularity in the ground will protect a prone man from a burst of .50 caliber machine gun fire that, had he been standing, would literally cut him in half. A bit of overhead cover - a few logs packed with dirt or a heavy door torn from its hinges - will shelter a soldier from the otherwise deadly splinters raining down from a mortar bomb bursting in the air.

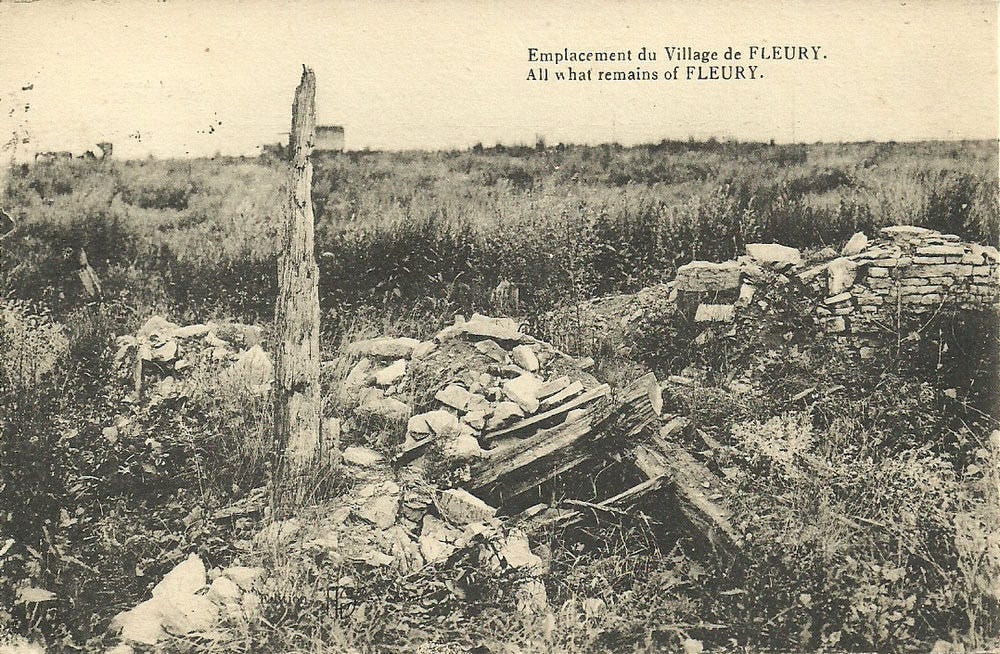

The ability of such simple expedients to deprive weapons of their decisive effect is well illustrated by the experience of Fleury, a tiny French village, which, during the First World War, had the bad luck to be located in the middle of the battlefield of Verdun. On the morning of the 22nd of June, 1916, twenty-six batteries of German heavy artillery reinforced by nine light batteries fired over 100,000 high explosive and poison gas shells on the village, on the “no man’s land” between the objective and the German lines, and on the French batteries supporting the defenders.

Despite the ferocity of the bombardment - an observer described Fleury as “one of the few towns which in the course of the World War was literally pulverized and blown off the face of the earth by long-continued, concentrated artillery fire” - a large number of French machine gunners, sheltering in cellars beneath the ruins of the village, not only survived the bombardment but retained the will to fight. The Germans had to clear the cellars one by one, with hand grenades and flamethrowers, before all resistance ceased in the ruins of Fleury.

What happened in Fleury has happened over and over again in modern history. Huge amounts of firepower poured down on defenders who are well dug-in succeeds in killing a few of them and wounding others. Some defenders are driven insane. All, no doubt, get splitting headaches. In most cases, however, the trenches or cellars are strong enough to allow some the enemy to survive the bombardment and to come out fighting once it stopped. In the words of an American Marine who saw this phenomenon first- hand in Vietnam - “They may have been bleeding from the ears, but they were still shooting at us.”

The phenomenon of men in battle surviving massive bombardments should serve to re- mind us of a key concept of maneuver warfare. The point of tactics is not just to do damage to the enemy - to hurt him a little and hope that he will run away. Rather, the true aim of tactics is to put the enemy into a trap from which there is no escape, a dilemma that he can only solve by giving up his fight against us.

Such a trap or dilemma is very much like a pair of pliers. By itself, each arm of the pliers can only push. This is true no matter how strong each arm is. However, when joined together in the right way, two arms combine to produce a strong grip - an effect that is many times stronger than the effect of many single arms.

Source: Douglas Johnson, Battlefields of the World War. Western and Southern Fronts. A Study in Military Geography (New York: Oxford University Press, 1921) page 366

Other parts of this article:

One of the things that comes to mind here is, as noted, that by leaving your enemies no way to escape or retreat, either physically or psychologically, they are thus encouraged to fight all the harder, even to the last. The battles for Fleury is a stark, but accurate example as were the battles for Stalingrad, etc. Commanders should be wary of pinching too tight unless they really desire annihilation of enemy and possibly friendly forces.