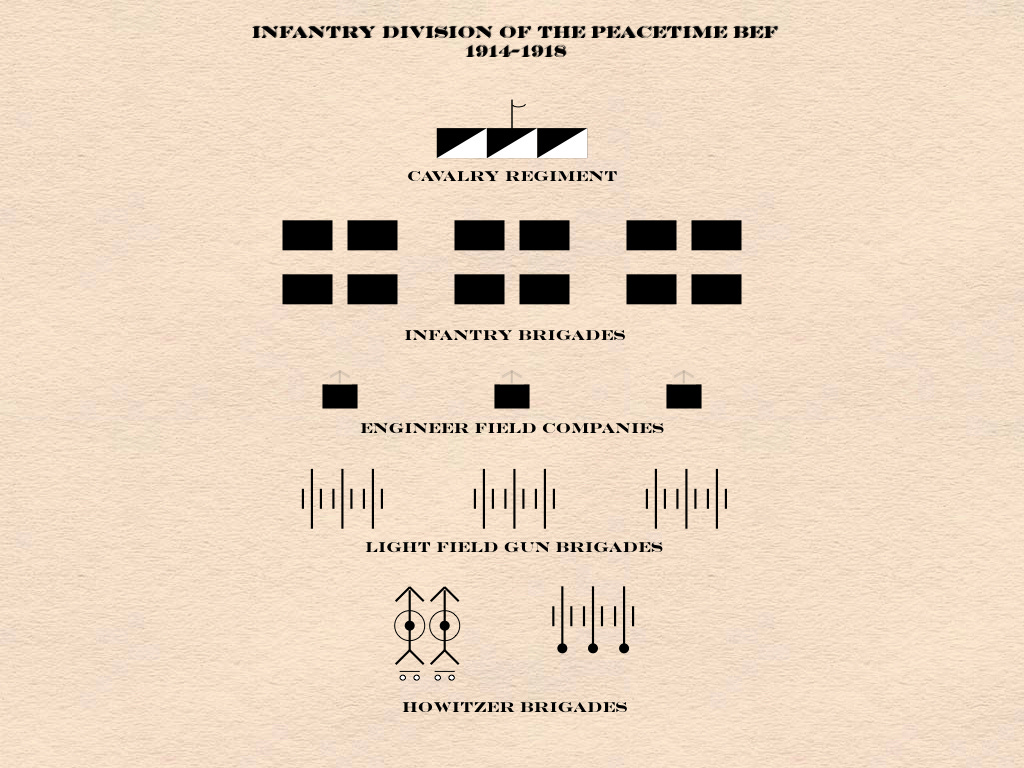

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of 1914 was a rare bird in the world of military establishments: a mature organization equipped with relatively new weapons. Thus, had it not gone to war in August of that year, it would have undergone few changes to either its order of battle or its armament. That said, the First World War broke out at a time when various agencies within the War Office had begun to contemplate a number of interesting reforms. This little essay explores the effect of these reforms upon the structure of the infantry divisions of the BEF in a world in which the Great War failed to take place.

The oldest artillery piece serving with the BEF in 1914 was the 18-pounder field gun. Introduced in 1904, it had been designed by veterans of the recent war in South Africa for service in conditions comparable to the ones that they had experienced. It thus possessed the virtue of being able to fire a shell heavier than that of any other weapon of its class out to distances beyond the reach of any other light field gun of the day. At the same time, it suffered from a recoil system that rarely returned the barrel of the piece to its original point of aim. (To make matters worse, the springs in this spring-based system required frequent replacement, either because they broke or because they lost their tension.)

For these reasons, the Ordnance had begun working on a replacement for the 18-pounder. This would be a lighter piece, with a caliber of 3-inches (7.62mm), a lighter shell, a higher muzzle velocity, and a split trail. (In addition to increasing the range of the piece, a split trail would allow the engagement of low-flying airplanes.)

As the new 3-inch gun was to be a one-for-one replacement for the 18-pounder, its introduction would do nothing to change the structure of the field artillery of the BEF. Each infantry division would thus continue to possess three field gun brigades, each of 18 light field guns, and a howitzer brigade, with 18 field howitzers. (Factory fresh in 1914, the 4.5-inch field howitzer would not need replacement for quite a few years.)

Under the leadership of Sir Stanley B. Von Donop, the Ordnance was also working on a 6-inch heavy field howitzer suitable for service with an infantry division. If Sir Stanley succeeded in this endeavor, a two-battery heavy brigade armed with such weapons might displace the battery of 60-pounder heavy guns that served as the only heavy artillery unit of the infantry division in 1914. (The latter weapon would, in all likelihood, be transferred to the siege train, where its long range would be appreciated and its heavy weight would be less of a handicap.)

If adopted, the new 6-inch heavy field howitzers would be the first artillery pieces in the BEF to be provided with automobile tractors of one sort or another. (Somewhat paradoxically, the next artillery piece to be motorized would probably be the 13-pounder light field piece of the horse artillery brigades of the cavalry division. Thus, by 1918 or so, the heaviest and the lightest artillery pieces in the BEF would be motorized while the pieces of middling weight would continue to depend upon horses.)

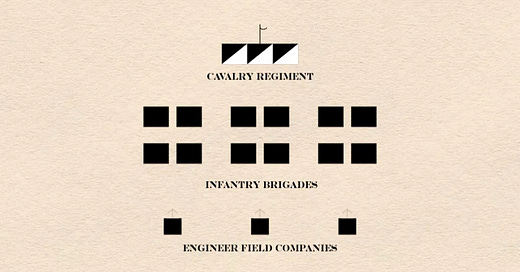

The only other structural change on the horizon in 1914 was the provision of a third engineer field company to each infantry division of the BEF. This reform, which would allow the assignment of such a company to each infantry brigade, would be made possible by the recruitment of “pioneers.” (These would be young men who were allowed to enlist in the Royal Engineers before they passed the “trade test” traditionally required for enlistment as a sapper.)