The Individual Replacement System in 1944

Combat Reports

During the Second World War, the U.S. Army kept its fighting units up to strength by a policy known as “individual replacement. ” Soldiers were given basic and specialist training in the United States, shipped overseas as anonymous “replacement drafts.” Once overseas, the replacements were kept in “replacement depots ” to until they were “requisitioned ” by a unit.

The effect that this had on the effectiveness of infantry units was nothing short of disastrous. Men who spent months as nameless, faceless transients were thrust into combat without even so much as an introduction to the men who were fighting beside them. Most had forgotten what they had learned in basic training. All were strangers to the other men in their squads, platoons, and companies.

These problems were eloquently described by the commanding officer of Company G, the 11th Infantry Regiment, a few months after the Allied landings in Normandy.

Let us consider the life of a replacement from the time he arrives in France. He is shoved from one replacement depot to another, and is made to feel that he is merely added weight. This gives the replacement an inferiority complex before he even starts. He is taken in a group and dealt off like a deck of cards into an organization. The old timers look at the replacements and then go back to their own circle. The old timers will always ignore recruits and this is bad for the replacement who may be fighting within the next day or two.

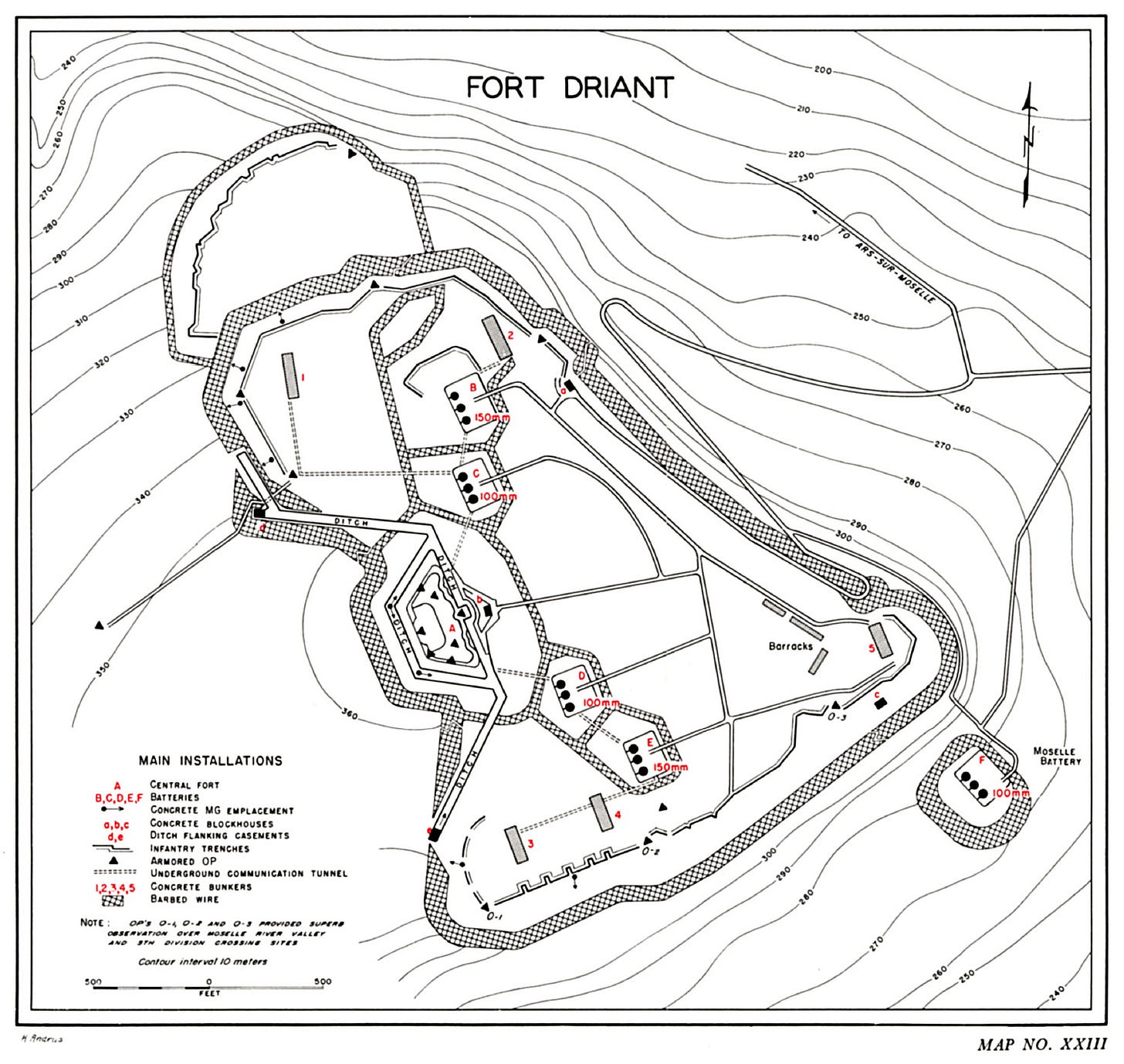

The replacements we received this time were antiaircraft personnel and had never been trained as infantry. I really had a problem on my hands; new officers with no combat experience and a fort to be taken. I took a dim view of trying to take Fort Driant with these men for I knew that they were not trained or hardened. They had little basic training and no assault training. I made a few squad leaders out of the old men that I had left. They were not too good, but they were the best I could get. They had been privates and privates first class in [Northern] Ireland. They had battle experience but lacked the necessary leadership.

We attacked Fort Driant and as I expected we could not take it. After additional planning we tried again. This time we breached the fort. After getting a good look at the fortification we knew that nothing except saturation bombing by block-busters would permit a reduction of the fort without excessive casualties.

In the second attack on the fort we had trouble with replacements. We could not get them to advance and had to drag them up to the fort. The old men were tired and the new men were afraid. During the three days we were in the breach in the fortifications we spent our time keeping the men in line. Most of the leaders were lost exposing themselves to get this done.

The new men seemed to lose all sense of reasoning — they left their rifles, flame throwers, demolitions, and machine guns lying right where they were. If it had not been for preplanned defensive artillery fires the Germans would have pushed us right out of the fort, for the men did not fight as they had been trained or disciplined to battle.

Editor’s Note: In addition to identifying the aforementioned problem of keeping men “in the fight,” the commanding officer of Company “G” identified a number of specific defects common to replacements.

He will say ‘yeah’ instead of ‘yes, Sir”; he is undisciplined.

He jumps at artillery shells.

He won’t shoot. Many have been told to hold their fire in order not to give away their positions.

He is usually in poor physical condition.

He lacks pride.

He is a ‘buncher.’

He won’t move.

He does not take care of his equipment.

He knows nothing about the rifle or the infantry supporting weapons.

He is afraid at night.

He knows nothing of formations.

Many of them evidently thought the war was over — they received a rude awakening.

He has never been battle inoculated.

He has no knowledge of sanitation in the field. Taking care of yourself in the presence of the enemy is a real job that has to be learned.

Editor’s Note: The following report from commanding general of the 29th Infantry Division describes that officer’s attempt to make the best of this system.

General. The 29th Infantry Division found that many replacements who went into action without time for proper orientation and introduction to battle, developed combat exhaustion after only 24 to 48 hours of combat. Of the first 552 combat exhaustion cases 208 were men with less than one week of combat. It was also found that many less serious combat exhaustion cases, which were the result of continuous front line action, could, with proper handling, soon be returned to duty.

Purposes. Accordingly, a training center was set up in the division area designed to serve two purposes:

To receive, quarter, orient, equip, indoctrinate and assign all replacements to the division.

To rehabilitate combat exhaustion cases.

Replacements.

Joining their unit. Replacements are assigned to a battalion but do not join it until the battalion is in a reserve area. This avoids rushing them in to the confusion of battle before they have a chance to become familiar with at least a few men in their squads, platoons, or companies.

Course of training. A minimum of one and a half days training is given to each man. It is designed to get them over the staleness of the long transit period, to refresh their training, and to re-familiarize them with their weapons. The schedule includes orientation on the division history, issue of equipment, assignment to a unit, 1000 inch range firing, close and extended order drill, several tactical demonstrations, and some practical work on small unit tactics.

Officers and noncommissioned officers . Officers and noncommissioned officers (NCOs)are given written examinations on the Soldier ’s Handbook and on supply discipline. Failure calls for additional training and re-examination.

Further training. Replacements whose battalions are not ready to receive them when they complete the orientation course, are given further training in physical drill, extended order drill and small unit tactics.

Non-commissioned officers’ school. To meet a shortage of NCO replacements for the rifle companies, an NCO school has been set up in the training center. One NCO or prospective NCO from each rifle company in the division attends. The course runs 10 hours per day for six days and includes a squad infiltration course, scouting and patrolling, squad and platoon tactics, issuance of orders, field sanitation and first aid, and the organization of a defensive position.

Combat exhaustion cases

Channels of evacuation . All combat exhaustion cases are evacuated from the front through normal medical channels and sent to the training center from the clearing station.

Screening . At the training center the men are screened by the division psychiatrist. Some are retained for rehabilitation, some are immediately returned to duty, and others sent to rear for further treatment or otherwise disposed of as conditions appear to indicate. Men who have broken down twice generally are not considered for return to combat.

Training program . During the training program the men refresh themselves on their weapons and at- tempt to regain the self-confidence necessary for a return to front line duty. The program runs from five to ten days, depending on individual requirements. The men are closely observed by the officers and NCOs conducting the train- ing and those who do not react favor- ably are further checked by the division psychiatrist.

Results . During ten weeks of operation the rehabilitation center in- creased the number of combat exhaustion cases returned to duty from 30% to 56.6%.

Staff.

Training section. The training and indoctrination group, exclusive of the NCO school, includes one major, commanding officer; one lieutenant, S-3 [training and operations officer]; one lieutenant, supply officer; and thirteen NCOs, sergeant or above, selected from wounded replacements with combat experience.

Medical section . The medical group includes the division psychiatrist and fifteen medical assistants.

Present replacements. The commanding officer of the division training center is commenting on the quality of replacements stated that “the replacements that we now get who received infantry training are average or better. Those trained originally for other arms have insufficient infantry training upon arrival. The men need constant disciplinary training. The biggest fault we find upon arrival here is a complete disregard of orders. Obedience to orders has not been sufficiently emphasized.”

Sources: Headquarters, Twelfth Army Group, Immediate Reports Numbers 83 and 87, dated (respectively) 23 October and 25 October, 1944. U.S. National Archives Record Group 337, Entry 47, Box 90.

For more vignettes of this type, see back issues of the Infantry Journal for the years 1946 and 1947. For the classic study of the impersonal personnel replacement system of the US Army of World War II, see Samuel Stouffer, The American Soldier: Combat and its Aftermath. For a shorter treatment that compares the American replacement system with its German counterpart, see Martin Van Creveld Fighting Power.

The individual replacement system is a heartbreaking way to treat people, period. However, it is deeply encouraging that the Commanding General of 29th Infantry Division recognized the problem and took steps to address the problems.

Despite the knowledge gained the Army repeated the mistake in Korea and Vietnam. The ease of the manpower process was more important than the combat needs of operating units. My experience in the USMC was such that we did stabilize units prior to deployment but kept filling those units up to the moment we boarded ships. This insured that the unit had upwards of 10 to 15% filled with Marines who had not fully participated in pre deployment training.