I found this paper, in 1990 or so, on the shelves of the library of what had just become the Marine Corps University. It bore the date of 31 August 1955, but no indication of the name of its author.

A Brief History of the Development of the Fire Team in the Marine Corps

In the Marine Corps the problem of giving its ground troops the maximum degree of fire availability has long been the subject of intensive study and experimentation. Although the term "fire team" is relatively new in the organization of a military group, the basic idea has had an evolutionary growth under various conditions of warfare.

The beginning of the "fire group" can be seen in the informal use (by the Corps) of (small) tactical units and patrols during the period from the Spanish-American War to the formation of the Fleet Marine Force in 1933-1934. For example, in the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Nicaragua, the Marines were faced with terrain and combat situations not covered by conventional tactical formulas. Bush warfare in these countries with the unusually rugged terrain of sand, rock, hills, and jungle features, which caused troops to be trail-bound, forced these Marines to undergo a change in their concept of the use of firepower. The jungle made it impractical for traditional deployment, minimized the use of the time-honored scout formation, and made the old attack formation completely useless. It was under these conditions that the idea of the "fire team" had its earliest practical conception in the Marine Corps.

Early in the Nicaraguan Campaign (1927-1933) it became evident that a small point sent ahead of a Marine patrol to act as an advance group could easily be lost on forking trails. Frequently the enemy separated the point from the patrol by a cleverly-devised ambush and annihilated it. The traditional formation of placing an automatic rifleman in the forefront of a patrol or at the spot in the patrol where the attack was expected, so that his fire could be immediately directed by the patrol leader, resulted almost invariably in an inconclusive fire fight. The first concentrated fire from an ambush usually made a casualty of the automatic rifleman if he was near the front or on an exposed flank.

Consequently, the Marines, in their own units and in the units of the Guardia Nacional which they trained, often ignored the squad formation and divided patrols into more practical units of fire power. Lieutenant Merritt A. Edson employed a formation that became somewhat of a standard in his subsequent patrol actions in Nicaragua. While on patrol, his unit marched in file formation and was divided into three sections of combat groups: (1) the point guard group consisting of three rifle- men and one automatic rifle, advancing in file, staggered on opposite sides of the trail; (2) the main body; and (3) the rear guard group consisting of three riflemen.

Another variation in the formation of a better organized fire group used by the Marines in Nicaragua consisted of the six-man group. Three riflemen led the patrol followed by the automatic rifleman; behind him came the patrol leader with a rifle grenadier acting as rear guard. A larger patrol would be simply a composition of six-man units. This type of patrol approximated the idea of the modern fire teams, but it was, of course, a very informal use of it -- and a use almost entirely limited to patrols.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, military thought on strategy and tactics became the main con- cern of the moment. With the subsequent employment of Marine Corps forces in the Pacific, new tactical developments came into being. As early as January, 1942, the Major General Commandant issued orders that selected personnel be assigned as observers to the British Commandos and to report back to the Marine Corps, information which might be of use in developing similar organizations. Captains Samuel B. Griffith and Wallace M. Greene, one of the observation teams, in their report dated 7 January 1942, gave the details concerning the development, organization, equipment, administration of Commandos.

Another team, consisting of Captains Russell Duncan and First Lieutenant William A. Wood, in their report dated 30 June 1942, presented facts and opinions concerning the history and organization of the Commandos. The substance of these reports were in turn assimilated and implemented by the Marine Corps and put into practice in the newly organized 1st and 2nd Raider Battalions. The effect of this action was given impetus by Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson, who was assigned to command the newly formed 2nd Raider Battalion. He had been a military observer with the Red Army in China in the 1930's and had carefully scrutinized their techniques in guerrilla warfare. He advocated a fire team of three men, though he did not center it on the automatic rifleman.

In the development phases of the Raiders various types of armament were tried. Captain Kimbrill of the British Army, who spent about a week with the newly organized 2nd Raider Battalion, recommended that the battalion be armed with more Thompson sub-machine guns than other weapons, since the range of employment varied be- tween six and sixty yards. He also stressed mobility. Lieutenant Colonel Merritt A. Edson who was assigned to command the newly created 1st Raider Battalion recommended improvements in the organization of the squad, but dealt with the standard rifle squad then in use. After a few experiments, Colonel Carlson decided to use the automatic rifle as the base of fire.

The theory behind the three-man group in guerrilla warfare was essentially quite different from that behind the first development of the fire group in Nicaragua or from the theory and practice finally developed on Guadalcanal and in succeeding operations. Thomas E. Lawrence, of Arabia fame, had laid down the principles upon which guerrilla fighting tactics were based. He tried to formalize the principles of guerrilla warfare in much the same way that principles had been standardized for regular combat.

The most important feature in such fighting, according to Lawrence, was that guerrillas, usually inferior in numbers, had to operate with few casualties in order to keep up both their strength and morale. Under this disadvantage they had to avoid massing troops, or allowing themselves to be drawn into large scale battles. The basic tactic of the guerrilla group was to strike and run, to destroy lines of communication rather than to conquer territory or kill the enemy.

The second main feature of Lawrence's thesis was that, whenever two men were together in guerrilla warfare, there was one too many. This principle, of course, was a subsidiary to the first. Here he over-emphasized his point; what he undoubtedly had in mind was that to make guerrilla warfare successful, the soldier had to depend upon his own resourcefulness and extreme decentralization of mobility of movement and firepower. Yet, in so doing, he had rendered all but impractical the application of his major principle to organized warfare.

Colonel Carlson's fire team of three men, then, was an extension of these principles but with a different objective in mind, namely, the achieving of the maximum effect from small groups of men rather than from individual effort. Carlson visualized the battles of the war as many small fire fights in which the general plan could be laid down by the squad leader who could not control the individual points of battle or the movements of the units after they had opened fire. The three-man fire group was a simple division of a nine-man squad which allowed greater flexibility in the formation of the squad. It was armed with the M-1, the Browning Automatic Rifle [BAR], and the Thompson sub-machine gun.

This tactical organization was used by Colonel Carlson's 2nd Raider Battalion on Guadalcanal in 1942. Since the Raider battalions were the newest type of military organization put into the field by the Corps, it was natural that they were among the first to experiment with and adopt various forms of fire groups. In the heavy action of Lieutenant Colonel Edson's 1st Marine Raider Battalion in the Battle of Edson's Ridge, Guadalcanal, 12-14 September 1942, the three-man fire group was probably used for the first time in a major combat action. In December, 1942, in summing up the results of his actions during his Aola-Point Cruz patrol, Carlson stated:

"The internal organization of the battalion left little to be desired. The squad organization with its three fire groups of three men each, worked beautifully. Worthy of particular note is the fire group, a team of three, armed with the M-1, BAR, and Thompson sub-machine gun, respectively, also developed in this battalion. The team of three was easily controlled when advancing by infiltration, and the group was useful in providing security for bivouacs."

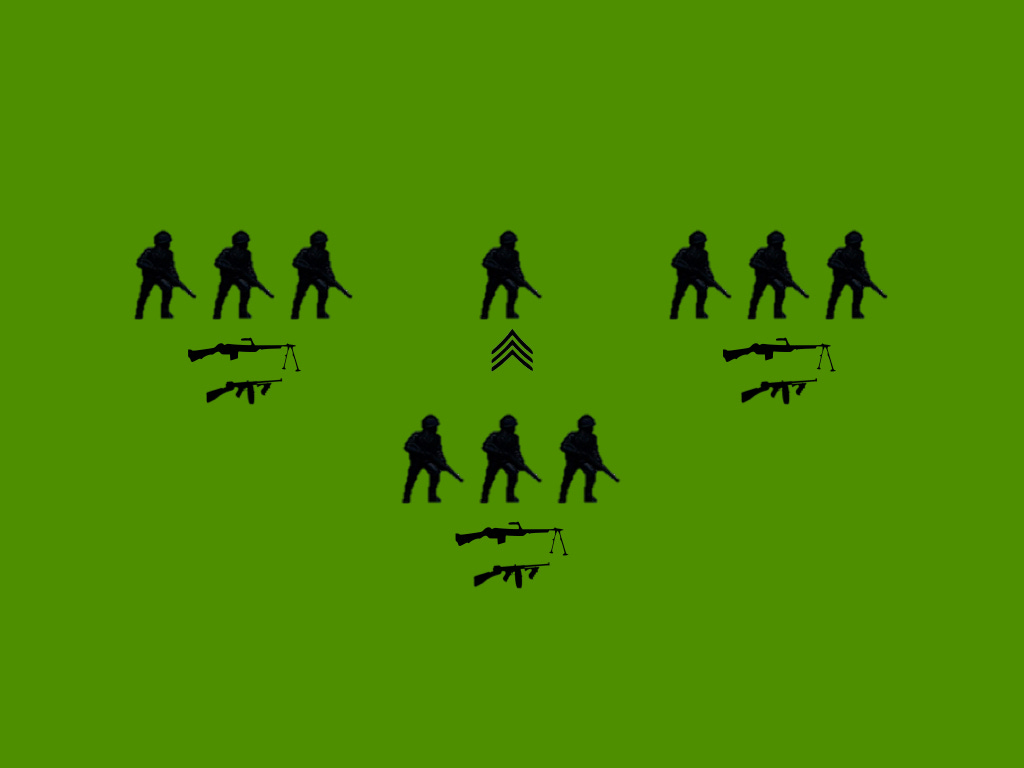

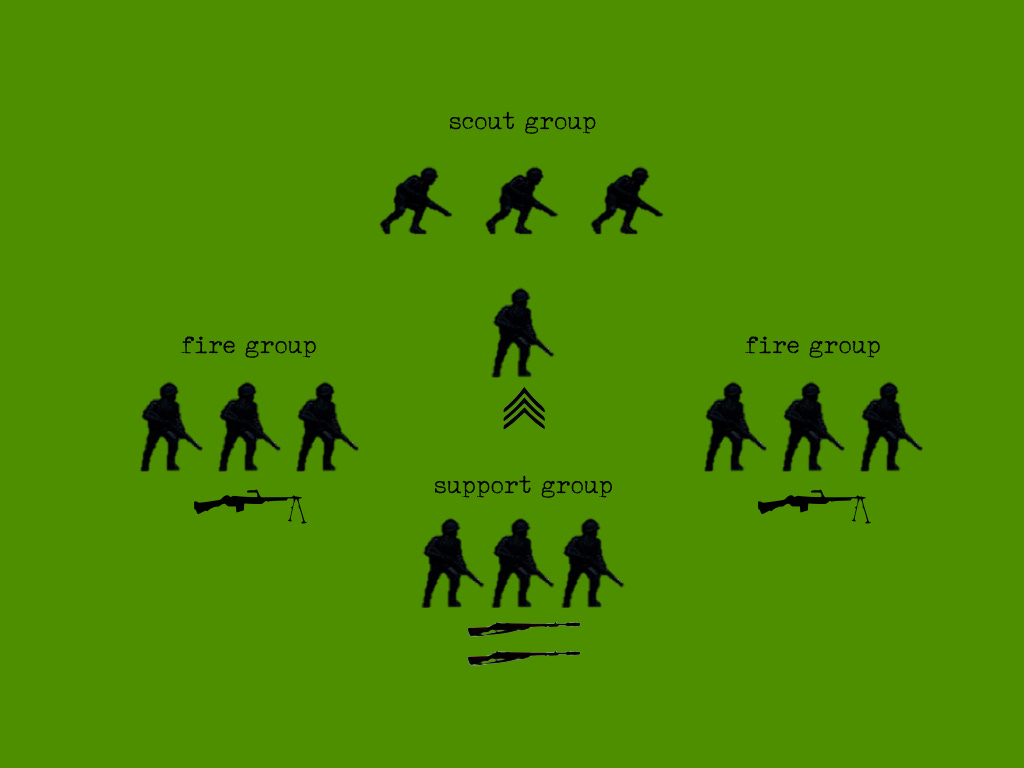

In the summer of 1943, Lieutenant Colonel Homer L. Litzenberg, commanding the 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines, and his staff began intensive experiments for the specific purpose of determining what structural and organic changes were needed to make the squad perform at its maximum efficiency. Prior to this time, most of the experiments in squad improvements were conducted within the framework of the existing tables of organization. Lieutenant Colonel Litzenberg began his experiments at this point but went one step further. With Love Company has his experimental factor, he formed the basic squad as follows: squad leader, a sergeant; scout group, a leader and two scouts; two fire groups, each with a leader and two men, one of whom was armed with an automatic rifle; and one support group, a corporal and a rifle grenadier.

These squads of Love Company were then put through a series of squad exercises, each covering a basic tactical maneuver. The tendency of the exercise to become mechanistic was overcome by using different terrain features, similar to those to be met in future battles. During the entire period of experimentation, the new formation showed up better in all respects than the old, in almost all situations. Within the old squad, individual action produced general confusion with the resultant loss of control by the squad leader. In the experimental squad, three-man groups worked as a well coordinated team, under the leadership of the best man in each group. Adaptations to immediate tactical situations were made quickly and surely with the least amount of confusion.

Application of fire, in the new set-up, was a vast improvement over the old. The first duty of the group leaders was to direct the fire of their men, which resulted in more hits with fewer shots. Other advantages were also apparent: training of subordinate leaders, development of teamwork within the squad, and more direct training in fire and movement. Throughout this experimental period, Colonel Litzenberg kept constant personal watch of the progress. Finally, after a series of demonstrations by one of the squads of Love Company, he adopted the group system for the battalion. On 2 August 1943, he forwarded the results of his experiments to the Commanding officer, 24th Marines, with the recommendation:

"that the rifle companies of the 24th Marines be organized on the group basis for exhaustive tests of this method with a view to its possible adoption by the Marine Corps. Until such time as an additional member of the squad is authorized, the support group in each squad can function with two men instead of three. It is suggested that the thirteenth man should be armed with rifle grenades."

Meanwhile, in the Vangunu operation in the New Georgia Group, 28 June to 12 July 1943, Lieutenant Colonel Michael S. Currin, Commanding Officer of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion, had used his own three-man group system to good effect. He had worked out a series of formations for squad, platoon, and company actions which kept, in all cases, the triangular formation of two units forward and one in reserve. In his September, 1943, summary he reported that the "organization of three man fire groups, three group squad, and three squad platoons has proven completely satisfactory ... The Thompson sub is no weapon for a man on the front lines."

In October, 1943, during the Choiseul diversion, the 1st Parachute Regiment, under the command of Colonel Victor H. Krulak, also used the three-man fire group with very good results. In his operation report of 4 January 1944, Colonel Krulak stated that the three-man fire group system provided:

"three cohesive jungle fighting teams, each built around a powerful automatic weapon. Arming one member of the group with a carbine is a practical means for providing a maximum of ammunition for the automatic rifle without materially reducing the fire- power of the group ... Inclusion of one antitank grenadier in each squad brings a powerful high explosive weapon directly to the front line, providing an effective counter for the knee mortar and a powerful adjunct in reduction of fixed defenses."

The special action report of the 3rd Marine Division for the Bougainville operation (1 November to 28 December 1943), submitted to the Commandant of the Marine Corps on 21 March 1944, contains as Enclosure F, the special action report of the 3rd Marine Regiment, which reads:

"The basis of all small patrols was generally the 'Four Man Fire Team' (three riflemen and one automatic rifleman) in either the wedge of the box formation. For example, a reconnaissance patrol might form a wedge or a box of wedges of four men each, with the leader of each team in the center. In combat, when contact was made by one of these teams with the enemy, the idea was that the automatic rifleman would cover the target, one rifleman would cover the automatic rifleman and the other two move in immediately to flank the target; the speed of reaction of the team generally measured the degree of success of the attack. Another important feature of the at- tack which was carefully observed was that the pair of flankers moved inboard of their formations so that their line of fire would be away from other fire teams in the formation."

As these reports on experiments with squad reorganizations came in from the field, they were channelled to Headquarters, Marine Corps. Upon receipt of a letter, dated 23 September 1943, from the Commanding General, 4th Marine Division, concerning the reorganization suggestions of the 24th Marines, the Commandant of the Marine Corps on 14 October 1943 directed the Commandant, Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Virginia, to take up the matter.

In December, 1943, a board of officers consisting of Lieutenant Colonel Samuel B. Griffith II, Major Lyman C. Spurlock, and Major Thomas J. Myers was appointed to study the various reports on squad reorganization and submit its findings at the earliest possible date. Each of these board members had led troops in jungle operations, and each had experimented with various types of squad organizations. They set as their main goal to find, through analysis and discussion, the type of unit which best combined maximum fire power and efficient integrated control.

From the first, the basic question was whether there should be three or four men in the fire team. Both systems could be used in the nine or twelve man squad. After many discussions, compromises, and criticisms, the four-man team was finally decided upon as the superior fire unit because it provided a little more flexibility. In the three-man team, if one man became a casualty, the offensive action of the team was seriously endangered and the BAR man was inadequately supplied with ammunition. Also, the three-man team provided no equal division of forces. Either the BAR man had to stay behind and allow the other two men to make the flanking movement, or he had to hold one man back with him as assistant ammunition bearer in case he himself became a casualty.

The question of armament also received a great deal of attention. It was early agreed that the BAR was necessary as a base of fire. It was also decided to arm the assistant automatic rifleman with an M-1 rifle. Thus, all members of the team could use the same ammunition, with the result that there would be a common pool and confusion would be cut to the mini- mum. However, when the board's recommendation reached the Division of Plans and Policies, discussion centered around this point -- what was the best arm for the assistant automatic rifleman? Two reasons were given against the use of the M-1: (1) with all men armed with M-1's, the BAR man might be left without an ammunition bearer in a fire fight and (2) the carbine was much lighter than the M-1 and the am- munition bearer could carry just that much more ammunition for the BAR. Thus, the Division of Plans and Policies recommended that the assistant BAR man be armed with a carbine.

On 7 January 1944, the board re- ported its findings to the Commandant, Marine Corps Schools. On 11 January, the Director, Division of Plans and Policies, issued a memorandum to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, in which he stated that from the many sources in the Corps, constructive criticisms had been gathered which would lead to a better and more efficient use of men and material. In Paragraph 2 of this memorandum he outlined the proposed change in the rifle squad.

Six days later, the change was incorporated into tentative Tables of Organization (T/ O's). These tentative T/O's in turn were sent out to Fleet Marine Force units in the field for comment. After return of the proposed changes, with notes, comments, concurrences, and non-concurrences, the subject was again discussed at Headquarters level. Finally, by the middle of March 1944, with the fine points ironed out from all angles the new T/O's were promulgated.

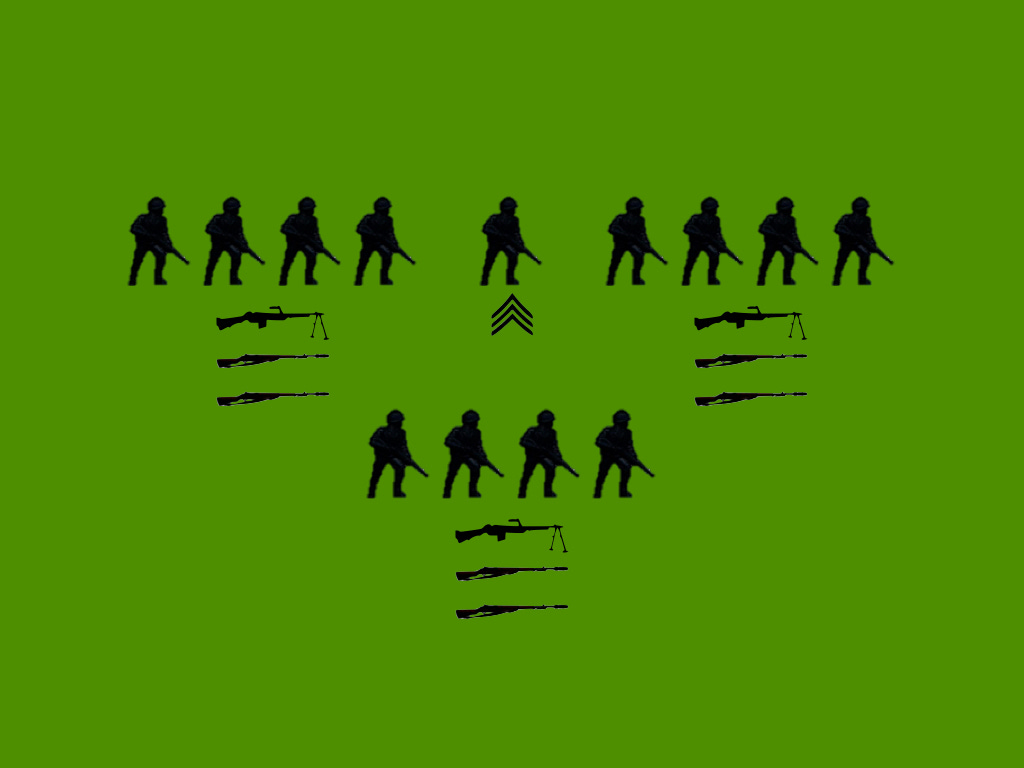

The Table of Organization for the rifle company was approved 27 March 1944. It was followed by Marine Corps Training Bulletins, Numbers 101 and 102, which described in more detail the breakdown of the fire team formation. The significant feature of the rifle company T/O was the fact that it broke down into squad sub-groups, thus dis- placing it as the smallest integral unit of combat. The primary innovation was the shift from the 12-man to the 13-man squad and the division of the squad into three fire teams of four men each.

One sergeant, the squad leader, was armed with a carbine. A corporal, armed with an M-1 rifle, bayonet, and grenade launcher, was put in charge of each fire team and designated the fire team leader. The other members of the fire team consisted of one rifleman armed with the M-1, bayonet, and launcher; one BAR man; and one assistant BAR man armed with a carbine. The new change left intact the triangular formation of three squads to a platoon and three platoons to a company.

In a large measure also, the new T/ O caused other radical changes which affected the entire infantry battalion. The BAR squad of the platoon was abolished (Editor's Note: This had actually been done almost a year earlier), along with the weapons platoon of the company and the weapons company of the battalion. The new T/O forged more efficient combat teams, each complete in itself, and gave the squad and the platoon more maneuverability and a considerable increase in fire power. Each company was given as part of its organic structure six heavy and six light machine guns and three mortars. In the company weapons pool each squad had available one flame thrower, one bazooka and one demolition kit. An anti-tank rocket launcher, M-1, (bazooka) was also included in the company weapons pool.

Although the new "F" Tables of Organization was officially established 27 March 1944, the wheels of the actual organizational change began to turn with the transmittal of the Commandant's letter of 17 January 1944 to all units in the field, enclosing proposed Tables of Organization, with the statement that the enclosed "change in organization of the Marine Division has been approved and will be accomplished when directed by this Headquarters."

After the Roi-Namur phase of the Marshalls operation, in February, 1944, the 4th Marine Division arrived at Maui, Hawaii, where it settled down for a well deserved rest preparatory for future operations. On 26 February, the Commanding General, 4th Marine Division, put into action the first stages of organizational machinery, acting upon the tentative changes as suggested by the Commandant's order of 17 January 1944. On 1 March, he issued orders to his regimental commanders to "proceed with the reorganization of their regiments immediately." A month later, 5 April 1944, the Commanding General, V Amphibious Corps, in his report to the Commandant of the Marine Corps, stated that the 4th Marine Division had finished its reorganization.

At about this time the 2nd Marine Division had also begun the task of reorganization. After its conquest of Tarawa, Gilbert Islands, the Division settled down on the island of Hawaii, T. H., for a period of rest and rehabilitation. From February to May 1944, the changes in organizational set-up took place. Doctrinally, then, as the invasion date of Saipan approached, the 2nd and 4th Divisions were ready to put the results of their organizational changes to the acid test of battle.

In summarizing their actions of Saipan, Divisional reports stated that the use of the fire team had definitely met and surpassed all expectations. Thus, from its official date of establishment to the present time, the four-man fire team, with the exception of a few changes in armament, proved beyond a doubt its place as an important unit in the Marine rifle squad. In all the battles since its establishment, this Marine fire team formation had functioned smoothly and efficiently.