Platoon (Background)

Decision-Forcing Case

Your name is Charles Victor André Laffargue.

You were born, on 24 September 1892, in the tiny village of Ligardes, in the south of France. (A census conducted the previous year counted 470 inhabitants.) Your father, who practiced veterinary medicine, was sufficiently prosperous to be able to send you to the preparatory school in the town of Agen, some 40 kilometers away.

As an adolescent, you devoted your leisure hours to the study of the obsolete military manuals and the memoirs of military officers that you found in the local flea market. Of these, your favorite is Lessons of the Russo-Japanese War, Impressions of a Company Commander. Published in 1906, this little book, described both the murderous effect of Japanese rifle and artillery fire upon the author’s regiment and the enthusiasm with which the Siberian riflemen of the company in question employed their bayonets.

In the autumn of 1911, having achieved high marks in the competitive examination for admission to Saint Cyr, you began a three year program designed to prepare you for a career as an infantry officer. (This program began with a year in the ranks of an ordinary infantry regiment and ended with two years of formal study at Saint Cyr.) In January of 1914, with your diploma in hand and the braid of a second lieutenant upon your sleeves, you reported for duty with the 153rd Infantry Regiment.

The commanding officer of the 153rd Infantry Regiment is Louis de Grandmaison. Well known for his writings about military history and theory, Colonel de Grandmaison advocates what he calls the “attack to excess.” Aggressive tactics, operations, and strategy, he argues, are not only well-suited to the temperament of French soldiers, but also the best way to win battles, campaigns, and wars in the shortest possible time, and thus at the lowest possible cost in human life.

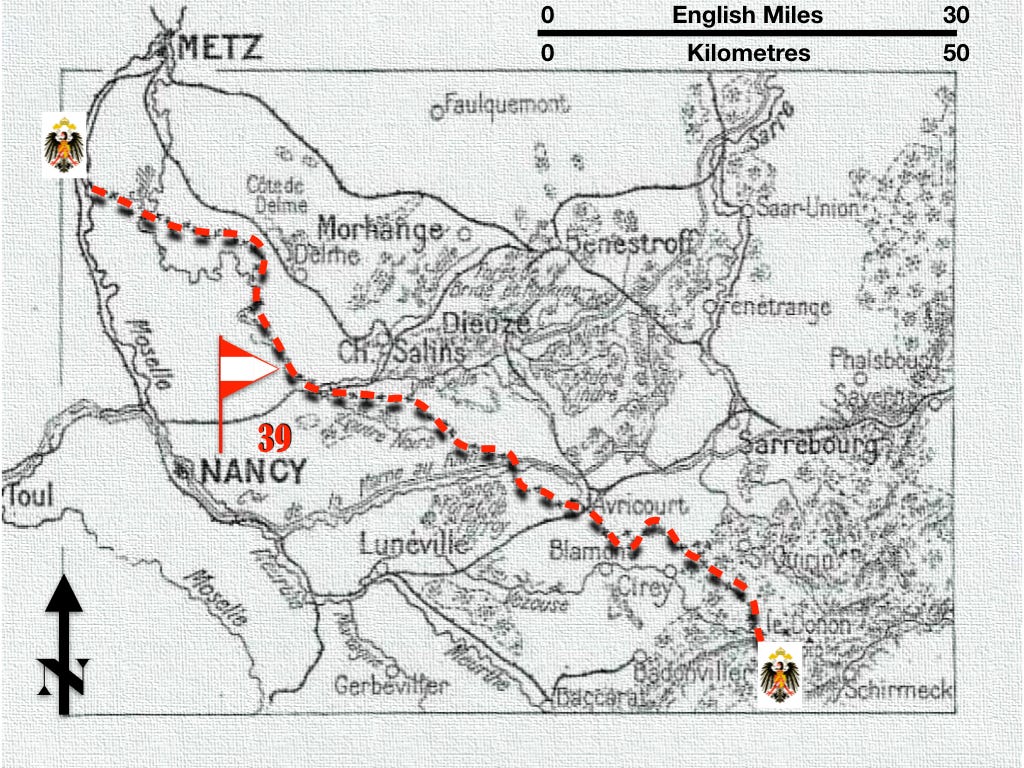

Located in the fortress city of Toul, near the border with Germany, the 153rd Infantry Regiment is one of the four infantry regiments the 39th Infantry Division. Informally known as the “Iron Division,” the 39th Infantry Division, is one of the handful of formations charged with guarding frontier regions while the rest of the French Army mobilizes for war.

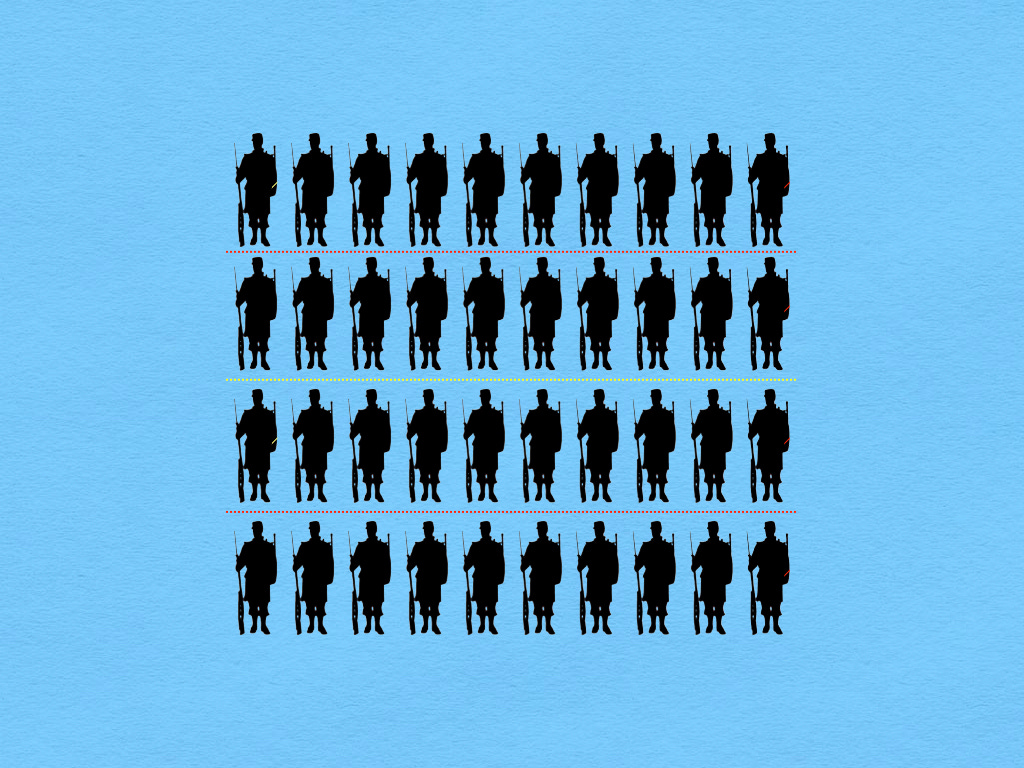

You command a platoon with a peacetime strength of two sergeants, four corporals, and thirty-four privates. Each of your sergeants leads a half-platoon of two corporals and seventeen men. Each of your corporals leads a squad of eight or nine men.

Some of your men, about a third of the total, have served with the colors for two years and nine months. Another dozen or so have been in uniform for twenty-one months. The remaining men reported to the barracks in October of 1913.

Towards the end of the month of July of 1914, seven hundred and ninety-three reservists report to your regiment. Of these, fifteen men, all of whom rank as privates, join your platoon.

The reservists, all of whom are men in their middle twenties, have been out of uniform for two or three years. Nonetheless, as most have earned their bread by means of physical labor, they are still reasonably fit.

On 31 July 1914, your division takes up positions between the city of Nancy and the German frontier. While the French Army as a whole has yet to mobilize, both you and your brother officers, as well as most of your men, are convinced that war is all but inevitable.

This series continues with the first problem, which, marvelous to say, is called Platoon (Problem 1).

Sources: André Laffargue, Fantassin de Gascogne, de mon jardin à la Marne et au Danube (Paris: Flammarion, 1962) and 153e Régiment d’Infanterie, Journal des Marches et Operations (31 Juillet 1914-31 Janvier 1915), Archives de Guerre, 26 N 697

Let us now in a step change at least as big as 1914 ~ Escarmouche à l'excès ~ Skirmish to Excess.