In January of 1940, Robert M. Danford, then serving as chief of field artillery of the US Army, asked officers of his branch to fill out a 'questionnaire on field artillery matters’, a substantial survey that, among other things, asked respondents to design an ideal field artillery establishment for a ‘triangular’ infantry division. (Where the infantry of a ‘square’ division consisted of four regiments, that of a ‘triangular’ division was formed into three regiments.)

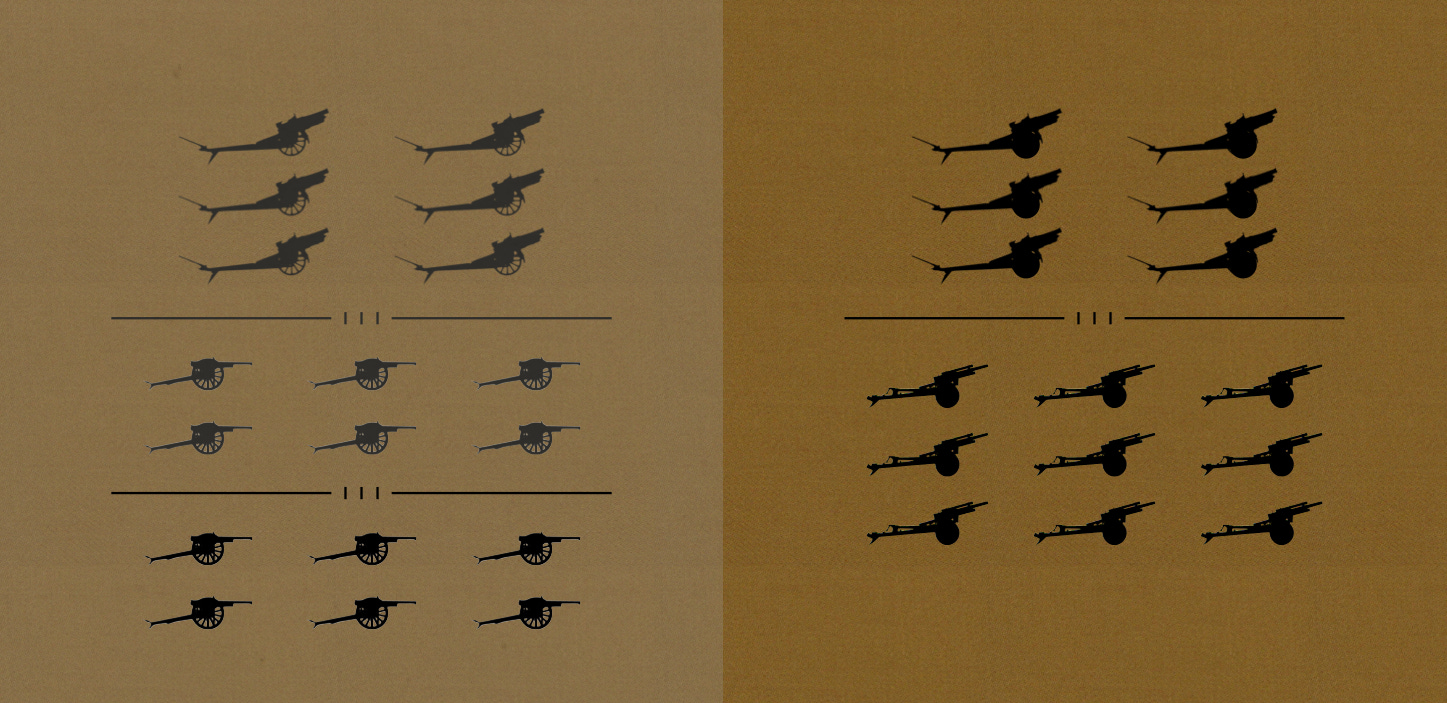

Of the forty-two officers who completed this portion of the assignment, fourteen recommended an organization that echoed that of the field artillery establishments of the infantry divisions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). That is, the members of this plurality argued for the provision of two ‘heavy’ battalions and a number of ‘light’ battalions that corresponded the number of infantry regiments in the formation. Thus, while the heavy battalions would fulfill missions of interest to the division as a whole, each light battalion would work closely with a particular infantry regiment.

The reduction of the number of infantry regiments in each division eliminated the need for one of the light artillery battalions. Thus, rather than possessing two light regiments, each of two battalions, the triangular division would receive, in the form of a three-battalion regiment, a single home for all of its light battalions.

The most popular of the organizational schemes retained the 155mm heavy field howitzers used by the heavy battalions of the AEF. At the same time, it replaced the old (Model 1897) field guns used in the First World War with the 105mm howitzers that were beginning to roll off American assembly lines. (The following diagram presumes that howitzers of both types were fitted with features - the most obvious of which were pneumatic tires - that made it easier for trucks to pull them.)

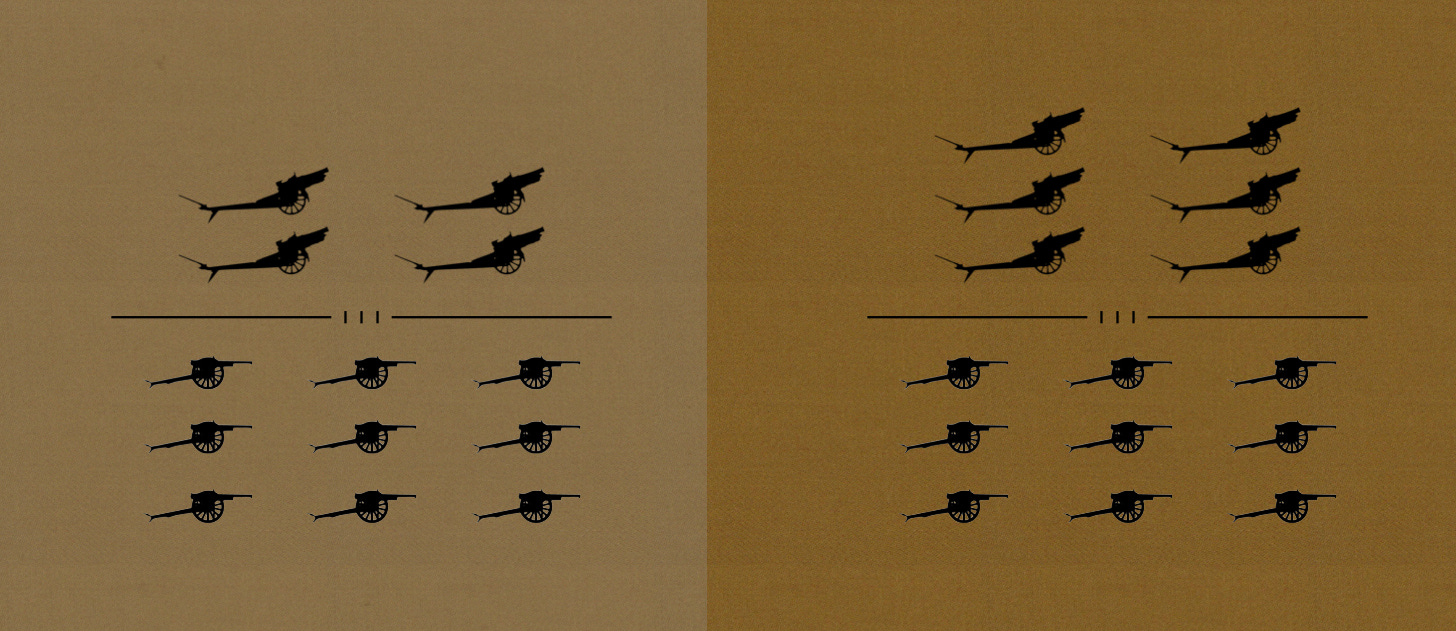

The silver medal, so to speak, went to a proposal to provide each infantry division with a pair of identical field artillery regiments, all of the batteries of which would be armed with 105mm howitzers.

With three champions, the most conservative of the proposals won a distant bronze. This design made but one change to the artillery establishment for infantry divisions adopted in 1939. That is, while the existing table of organization and equipment called for four batteries of 155mm howitzers and nine batteries of 75mm field guns, this scheme increased the number of 155mm howitzer batteries to six.

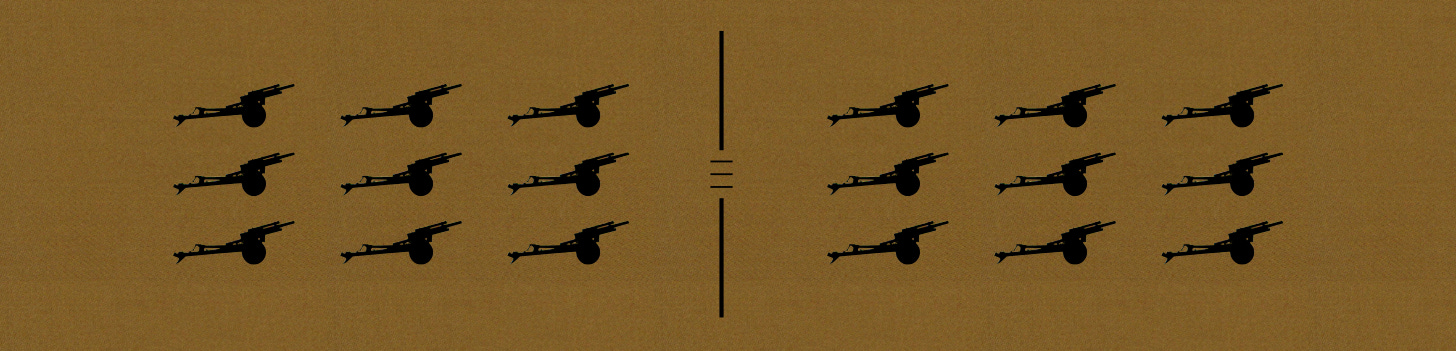

The remaining designs called for combinations of different sorts. Of these, five made use of 75mm pack howitzers, seven employed 75mm field guns, and five a combination of 105mm and 155mm howitzers different from that of the most popular scheme.

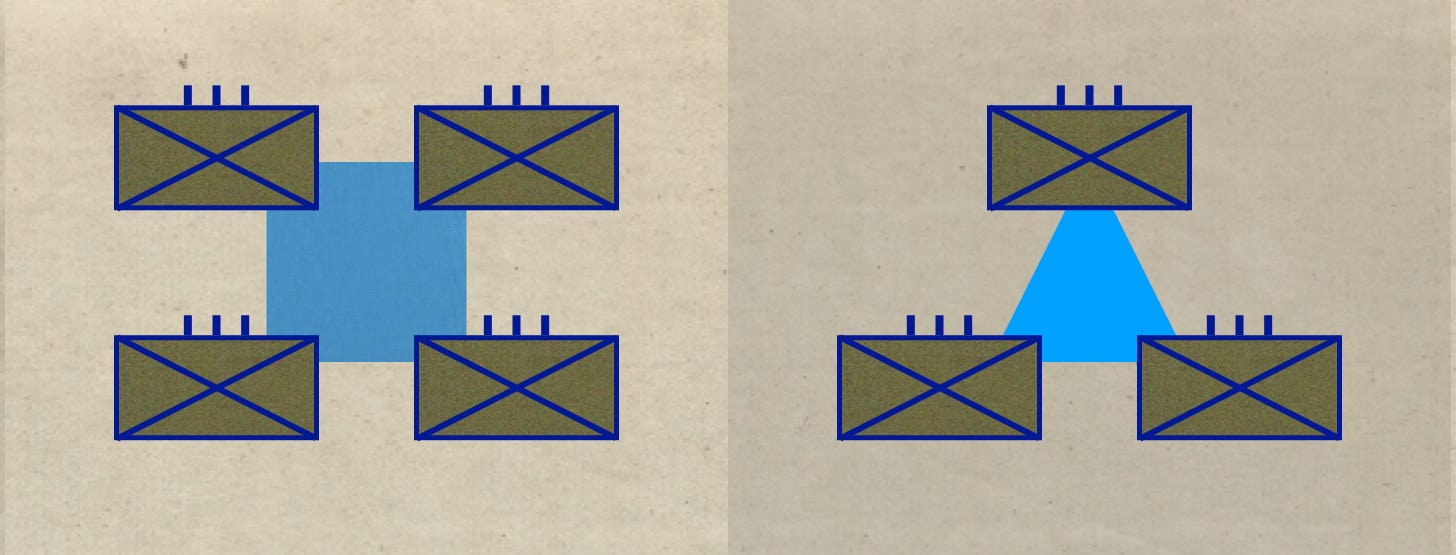

All but two of the designs provided each battery with four guns or howitzers. Of the outliers, one proposed the uniform adoption of six-piece batteries while the other combined six-piece field gun batteries with four-piece howitzer batteries.

In all, the respondents to the questionnaire sent out by Major General Danford provided him with a total of nineteen different designs for the field artillery of an infantry division. Unfortunately, the anonymous author of the document that summarized these schemes failed to provide complete descriptions of sixteen of these.

Sources

The links will take you to pages on the publications catalog of the Center of Military History.

Analysis of Questionnaire on Field Artillery Matters, unsigned, undated document found in Folder 320.2 AA-65, Box 17, Record Group 177 (Records of the Chief of Field Artillery), US National Archives.

Janice E. McKenney The Organizational History of Field Artillery 1775-2003 (Washington: US Army Center of Military History, 2007) page 58

John B. Wilson Maneuver and Firepower: The Evolution of Divisions and Separate Brigades (Washington: US Army Center of Military History, 1998) page 134

For Further Reading

Which is certainly not what the triangular divisions wound up with!