Operational Command in the South Atlantic

In, and around, the Falkland Islands in May and June of 1982 (Part I)

Welcome to the Tactical Notebook, where you will find more than four hundred tales of armies that are, armies that were, and armies that might have been. If you like what you see here, please share this article with your friends. If, however, the Tactical Notebook strikes you as tiresome, supercilious, or just plain wrong, please share it with your enemies.

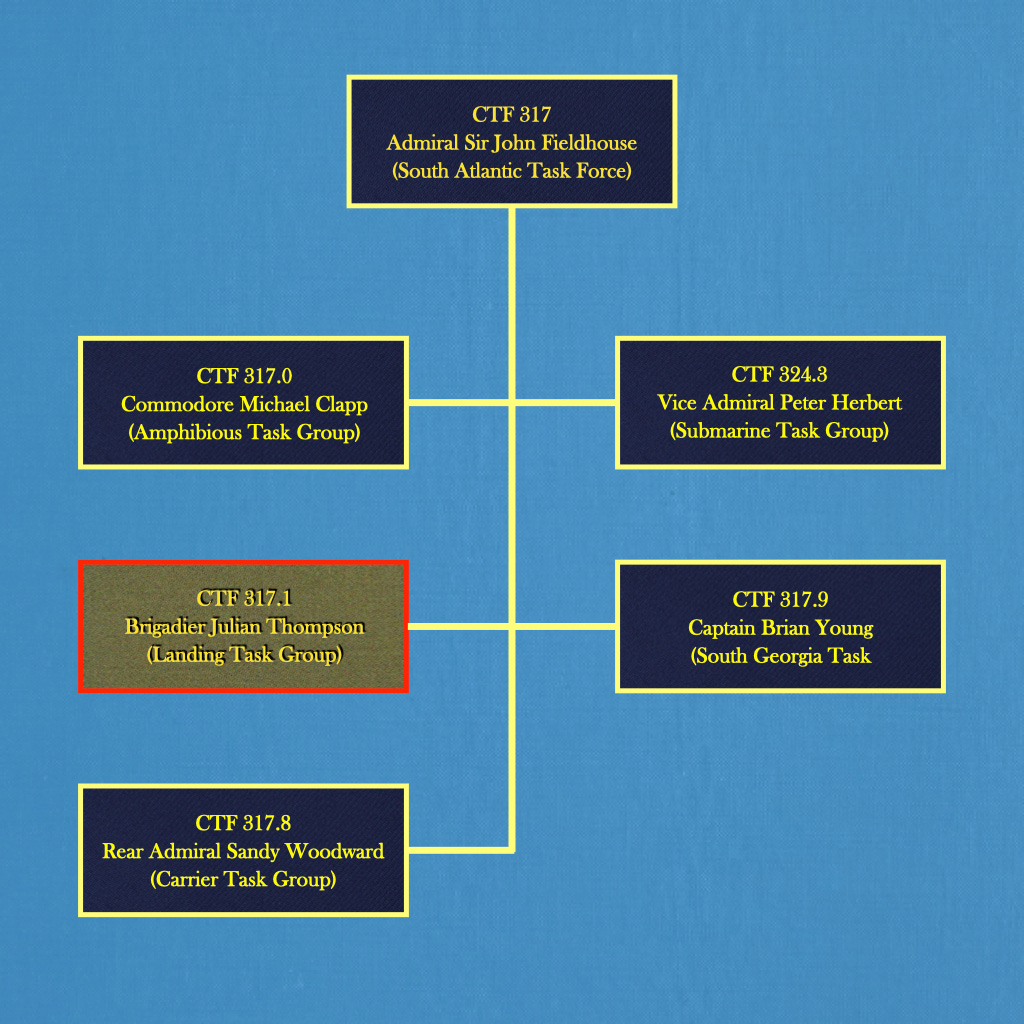

On 9 April 1982, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse organized the British task force en route to the South Atlantic into five task groups. Of these, three were charged with working with each other in order to liberate the Falkland Islands, one consisted entirely of submarines, and one was a separate expeditionary force formed to recapture the island of South Georgia.

The officer commanding each of the task groups reported directed to Admiral Fieldhouse. Thus, regardless of the rank he wore, he enjoyed the same functional status as the commanders of the other four task groups.

In the cases of the two self-contained task groups, those charged with underwater operations and the expedition to the island of (and islands near) South Georgia, this arrangement worked well. Indeed, as each was able to fulfill its mission without making major demands upon the resources of any of the other task groups, opportunities for disagreement rarely, if ever, arose.

Alas, the relationships among the chiefs of the three task groups oriented upon the Falkland Islands did not display the same degree of harmony. To be more precise, while the commanders of the amphibious flotilla and the landing group worked well together, the commander of the carrier task group often found himself at odds with his peers.

This situation stemmed, in part, from the backgrounds of the members of the Falkland Islands troika. The commanders of the amphibious and landing groups had spent many years preparing to fight in places where land and water come together. As a result, each had enjoyed many opportunities to practice the art of making trade-offs among the many competing demands of forces optimized for each environment. The commander of the carrier task group, however, had specialized in service in submarines and aboard surface combatants. Thus, while he had spent much time on the high seas, he had little, if any, experience of working closely with soldiers ashore.

The personalities of the two amphibians, moreover, quickly proved compatible. Both Commodore Clapp, of the Royal Navy, and Brigadier Thompson, of the Royal Marines, practiced of the art of separating the professional from the personal. As a result, they invariably proved able to work through differences of perspective without putting amour propre at risk. The same, however, could not be said for the blue water specialist. Indeed, if we are to believe his memoirs, Rear Admiral Woodward seems to have been the sort of person who rarely ran short of umbrage.1

Worst of all, the definitive problem faced by the commander of the carrier group differed from that of his two colleagues. While the team of Clapp and Thompson dealt with a conventional calculus of victory and defeat, Woodward found himself in the position of Jellicoe at Jutland. That is, while his command could not, by itself, achieve the goals of the war, he faced the very real possibility that the sinking of too many British ships would convince the prime minister to abandon her quest to recover the Falkland Islands.

Fear of losing the war by losing ships also afflicted Admiral Fieldhouse, who commanded all British forces in the South Atlantic from his headquarters at Northwood. Separated from the seat of government by a one-hour car ride, Northwood provided an excellent perch for a commander dealing with matters of strategy and policy. It offered two advantages, however, to an officer conducting a campaign in a place more than twelve thousand kilometers away.

Thanks to his proximity to both the Chiefs of Staff and the War Cabinet, Fieldhouse often found himself transmitting the instructions of service chiefs and politicians. However, rather than taking the form of comprehensive directives that aligned operations with the larger purposes of the war, these imposed specific limitations on the use of particular platforms. Thus, for example, Fieldhouse forbade the sailing of the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2 into waters where it might be attacked and the movement of the amphibious ships Fearless and Intrepid into an inlet (Bluff Cove) close to the location of the main body of the Argentine land forces.

Apart from imposing limitations of the aforementioned sort, Fieldhouse practiced a style of command that historian Martin Samuels describes as “umpiring.” Like those who lead by means of “directive command,” he allowed his subordinates considerable latitude to solve the problems that they encountered. However, while devotees of directive command take great pains to provide a firm framework for such functional freedom, umpires let subordinates work out such arrangements for themselves.2

This approach made possible a situation in which the three task group commanders directly concerned with the Falkland Islands operated from two different locations. That is, while Thompson and Class conducted their campaign on, and around, the islands themselves, Woodward kept himself, and most of the platforms he controlled, in open waters well to the east of the archipelago.

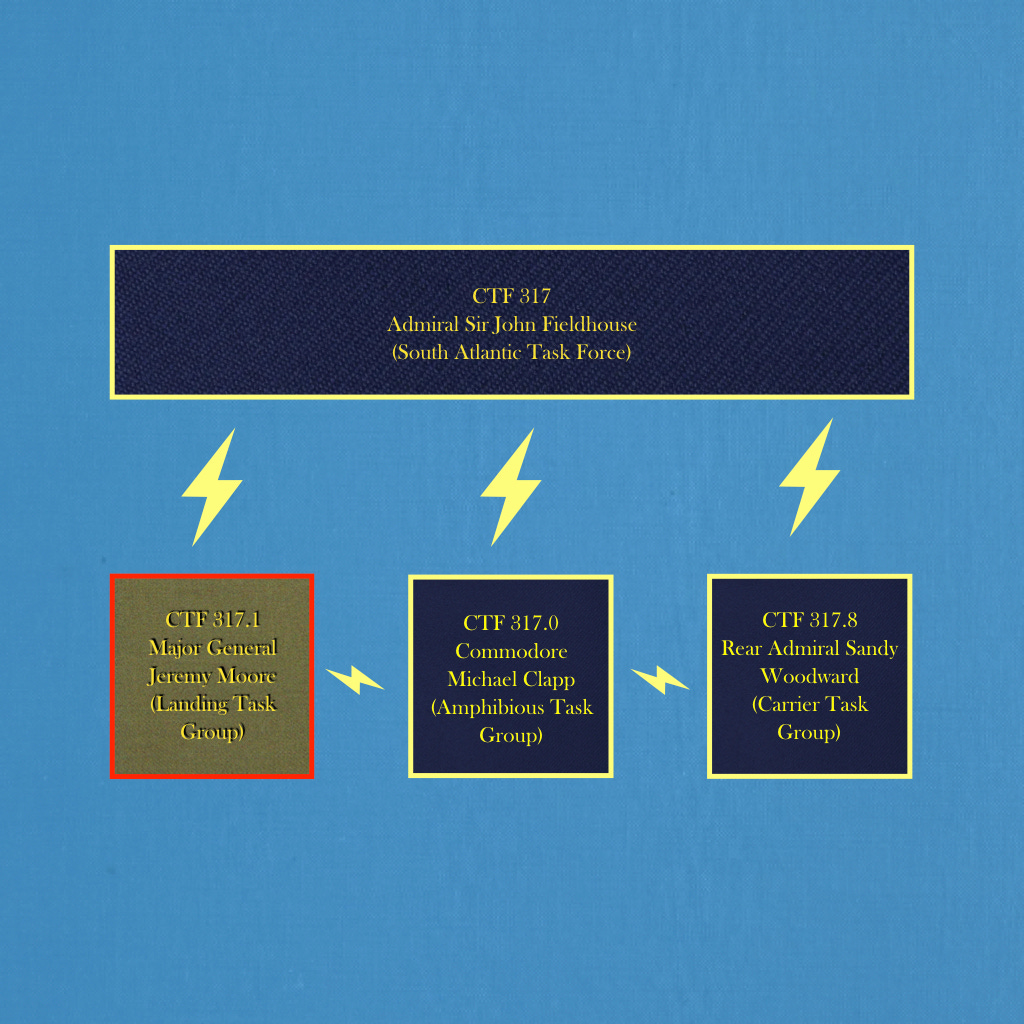

On 2 June 1982, Major General Jeremy Moore replaced Brigadier Thompson as the commander of Task Group 317.1. This change, however, did little to alter the relationships among the three interdependent subordinates of Admiral Woodhouse. Moore and Clapp quickly established a working relationship that proved as harmonious as the one it replaced. At the same time, the fact that Major General Moore wore a rank equal to that of Rear Admiral Woodward did little, if anything, to promote cooperation between them.

The allocation of various radio sets precluded direct calls between General Moore and Admiral Woodward. Thus, if either of the two-star commanders wished to send a message to the other, he had to route it through Admiral Fieldhouse or Commodore Clapp.

As neither Moore nor Woodward wished to involve the commander-in-chief in too many frank discussions between colleagues, most communications between them put Clapp in the awkward position of intermediary. To make matters worse, the radio connection between Clapp and Woodward suffered from technical difficulties. As a result, Clapp would later recall, Woodward’s voice reminded him of that of a Dalek, thereby making it “extremely difficult to hold an easy and relaxed conversation.”3

I have enjoyed many meetings, several long conversations, and extensive correspondence with both Michael Clapp and Julian Thompson. My knowledge of Sandy Woodward, however, rests entirely on words committed to print.

For the taxonomy of command styles developed by Dr. Samuels, see Martin Samuels Piercing the Fog of War: The Theory and Practice of Command in the British and German Armies, 1918-1940 (Warwick: Helion, 2019), pages 10-11. Earlier versions of the same paradigm can be found in Martin Samuels, “Understanding Command Approaches” Military Operations (Winter 2012) and “Friction, Chaos and Order(s): Clausewitz, Boyd and Command Approaches” Journal of Military and Strategic Studies (2014).

Michael Clapp and Ewen Southby-Tailyour Amphibious Assault Falklands: The Battle of San Carlos Water (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2007), page 123. (In the British television series Dr. Who, the Daleks were robot-like aliens who spoke in a stereotypically mechanical manner.)

Daleks...

yah baby

An outstanding job they did down south as well.