Mass

Tactics Made Simple

“Mass” is one of the most common words in the military lexicon. It appears on most lists of “principles of war,” including the one currently approved by the U.S. Army and the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It also pops up frequently in such phrases such as “mass tank attack,” “massed artillery fires,” and “anti-tank missiles are best employed in mass.”

The basic concept is simple - more combat power is generally better than less combat power. Applying the concept, however, requires a bit of elaboration. In particular, commanders who wish to make mass work for them need to answer to fundamental questions. First, how does mass work? Second, how much is enough?

The basic mechanism that makes mass work on the battlefield is redundancy . The more weapons we send into battle, the greater are the chances that some will survive the combined forces of Murphy’s Law and enemy action.

How mass works is nicely illustrated by the massed tank attacks of the Second World War. At all times during that conflict, tanks were very vulnerable to anti-tank guns. A duel between a tank and an anti-tank gun of a corresponding class (a French 25mm anti-tank gun versus a German Mark III tank) would almost always end with a burning tank and unharmed anti-tank gun crew.

There were a number of reasons for this. Tanks were far bigger than anti-tank guns, and thus both harder to hide and easier to hit. Tanks made a lot of noise when they moved, advertising their location, movements, and, to a certain extent, their intentions. Finally, tank commanders were less able to observe, whether by sight or by sound, the many things that were going on in the vicinity of their vehicles. (This was especially true when the tanks in which they were riding were “buttoned up.”)

The advantage of the anti-tank gun in “fair fights” was amply demonstrated in the Spanish Civil War. Tanks sent into battle in proverbial “penny packets” were dispatched with painful regularity by both purpose-built anti-tank guns and field guns pressed into service as anti-tank weapons. Because of this, many observers of that conflict went so far as to claim that the tank was obsolete. The anti-tank gun, they argued, was to the tank was the machine gun was to infantry.

One of the many surprises of the Blitzkrieg campaigns of 1939 and 1940 was the failure of the technical advantage enjoyed by the anti- tank gun to translate into tactical success. One reason for this great disappointment can be found in the way in the German use of motorized infantry, artillery, smoke, and other weapons to destroy, suppress, or blind the crews operating anti-tank guns. Another resulted from the way that the Germans handled their tanks.

When going into battle, the officers commanding German Panzer battalions often deployed their tanks in tightly packed formations. If one of these formations ran into a single anti- tank gun, there was a good chance that, during the first few seconds of the encounter, the gun would be able to disable one, or even two, tanks. While this was going on, however, the remaining tanks in the formation would have become aware of both the presence and the location of the anti-tank gun. They would thus be able to do such things as deluge it with machine gun bullets and high explosive shells, or, better yet, run over it.

Of course, if the fifty or so tanks in mass formation ran up against a similar number of anti-tank guns, the antitank guns stood a good chance of carrying the day. The odds of so many anti-tank guns being in one place at one time, however, were so slim that this was unlikely to happen. The defending commander, after all, would not know exactly where the tanks would attack. Because of that he would have to spread his anti-tank guns throughout his force, thus ensuring that there never would be enough anti-tank guns in any one location.

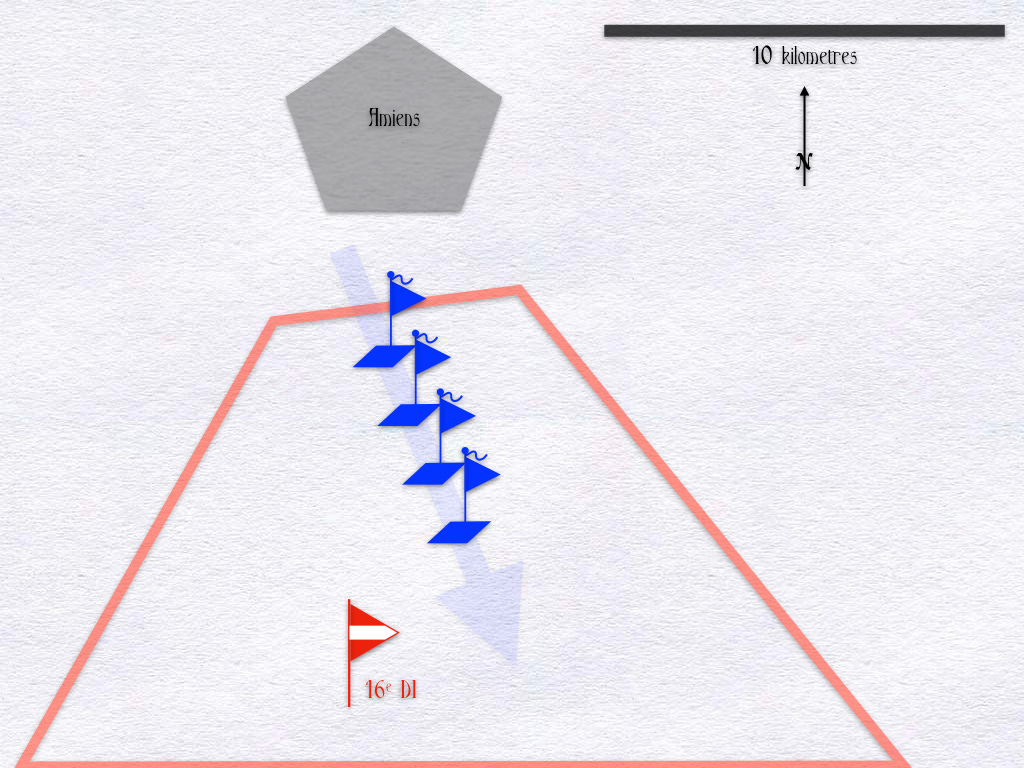

This phenomenon enabled the German 10th Panzer Division to break through the zone defended by the French 16th Infantry Division, then defending the Plateau de Dury just south of the city of Amiens, on the 6th of June, 1940. In this battle, the 10th Panzer Division had about 180 tanks. The 16th Infantry Division had a 130 or so anti-tank guns, each of which was capable of knocking out, with the first or second round, any German tank that it might encounter. However, as the French anti-tank weapons were spread out over an area of some 60 square miles (155 square kilometers) and the German tanks advanced in a column of four massed battalions, the latter never had to deal with more than twelve anti-tank guns at any given time.

The men who served the French anti-tank guns fought with both bravery and skill. Indeed, on average, each anti-tank gun crew that found itself in the path of attacking Panzer battalions was able to render three German tanks hors de combat before suffering its own destruction. Nonetheless, such virtuosity could not overcome the advantage enjoyed by tanks attacking en masse.

For those examples what is the difference between Mass and Concentration?

Plus, the Germans had air superiority. Airpower was crucial to Germany's early victories, as their opponents were largely fielding obsolete aircraft built by pacifists.

In the modern age, massed columns are a lot harder to pull off because massed artillery and tactical nukes can obliterate them.