JFC Fuller and the 90th Light Division

Theory and Practice

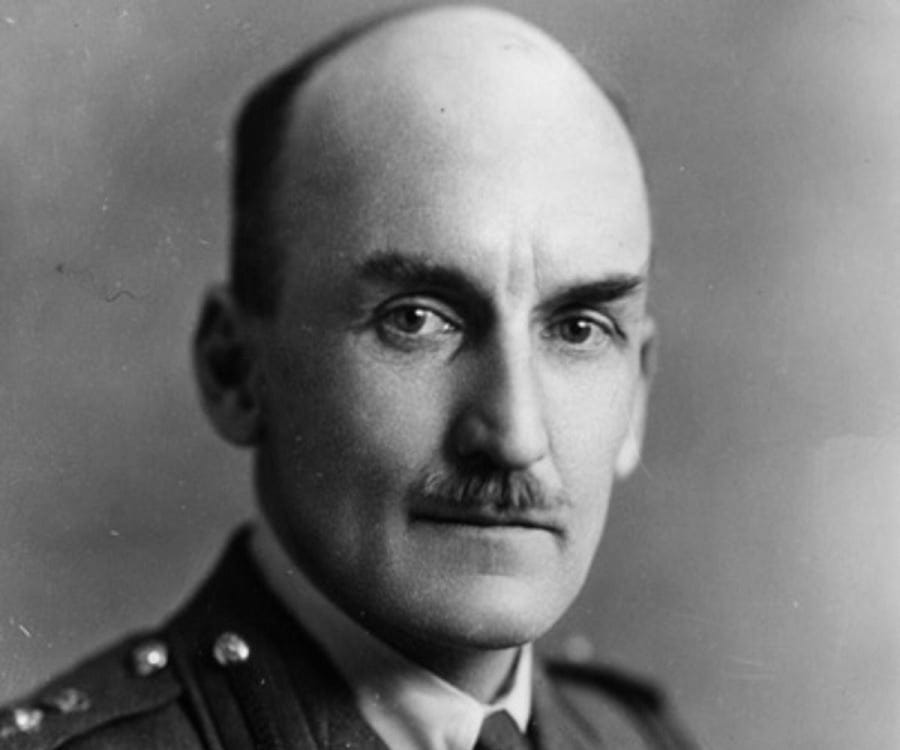

British military theorist JFC Fuller first encountered the tank during the First World War. Fifteen years later, after much thought, he published his mature ideas on the subject of mechanized warfare in a short book called Lectures on FSR III. As the title suggests, this work started out as a series of talks commenting on the field service regulations (“FSR”) that Fuller thought ought to be written on the subject of armored warfare. (At that time, the British field service regulations consisted of only two volumes - FSR I and FSR II.)

Fuller’s theories of armored warfare came closest to realization in the deserts of North Africa. There, for more than a year, Rommel’s mechanized army operated like the battle fleet of a weak but aggressive navy. When opportunities arose, it would sally forth to strike tempting targets. When the main body of its adversary responded, it withdrew to its fortified harbor.

In the spring of 1942 the German expeditionary force in North Africa went even further in its unwitting fulfillment of Fuller’s prophecies, chief of which was the notion that the proliferation of tanks on the battlefield would force infantry battalions and field artillery batteries to convert themselves into anti-tank units. The most extreme case of this metamorphosis is the reform of the seven mobile battalions of the German 90th Light Division in March of 1942. (Four of these were truck-mobile infantry battalions. Two were motorized anti-tank battalions. One was a motorized field artillery battalion.)

The four infantry battalions, described by the commanding general of the 90th Light Division as “entire arsenals,” were expected to serve either as conventional motorized infantry or as anti-tank troops. For the former task they had a full complement of light machine guns, heavy machine guns, mortars, and infantry guns. For the latter duty, each squad was provided with one of the many 7.62cm “divisional” guns captured from the Soviets in 1941.

A direct descendant of the M1902 “Putilov” field gun of World War I, the “divisional” gun enjoyed a high muzzle velocity, a flat trajectory, and a choice of projectiles. Firing an anti-tank shell, it was second only to the famous 88mm dual-purpose gun as a tank-killer. Firing high explosive it served as a first class infantry gun and an only slightly obsolescent field gun. Indeed, it was a good enough anti-tank gun to equip one of the specialized anti-tank battalions of the 90th Light Division and a good enough field piece to arm the single field artillery battalion. (The second anti-tank battalion was provided with 50mm anti-tank guns of German manufacture.) In other words, the principle weapon of six of the seven combatant battalions of the 90th Light Division was a “triple purpose” gun.

Despite making use of the same weapon, the six battalions of the 90th Light Division armed with the 7.62mm gun differed considerably in terms of equipment, training, and internal organization. The infantry battalions were much more capable of close combat than the anti-tank and field artillery battalions. Likewise, the field artillery battalion was the only mobile unit within the 90th Light Division with the skill and special instruments needed to arrange for indirect fire. Ability to make full use of anti-tank guns was also less than uniform. A young infantryman serving in the 90th Light Division in the spring of 1942 recalled that he had received no training on the anti-tank gun that was towed behind his squad’s truck. The first time that he and his comrades fired it was in combat.

The 90th Light Division’s status as the world’s first “anti-tank division” did not last long. When Tobruk fell to Rommel, enough trucks were captured to motorize those parts of the 90th Light Division that had not been able to operate with the seven “anti-tank capable” battalions. These elements - two infantry regiments and a few artillery batteries equipped with captured French weapons - doubled the size of the 90th Light Division. In so diluting the proportion of anti-tank troops, it gave the division a more conventional appearance.

In July of 1942, another blow was struck against both the 90th Light Division and its connection with Fuller’s theories. On the 1st of that month, the four battlegroups of the 90th Light Division ran into the concentrated fire of a division’s worth of South African artillery. So heavy was the fire that panic broke out in all four of the battle groups. And while order was soon reestablished, the 90th Light Division advanced no further that day.

Sources:

The descriptions of German units comes from Ulrich Kleeman, 90. leichte Afrika-Division: April - Sept. 1942: Streiflichter zur Kriegsführung in Nordafrika, D104, Foreign Military Studies. (Unlike many reports in the Foreign Military Studies series, Kleeman’s work has yet to appear in English. Paper copies of the German original can be found at the German military archives in Freiburg; at the US National Archives in College Park, Maryland; and at the US Army Military Heritage and Education Center at Carlisle, Pennsylvania.)

Lectures on FSR III (Operations between Mechanized Forces) made its debut in 1932. During World War II, a second edition, embellished by commentary, appeared under the title of Armoured Warfare.

I describe the proposed reorg here:

https://rommelsriposte.com/2011/06/01/a-hard-lesson-learnt/

It would have applied to all rifle battalions I believe, and came from 15. PD, who seem to have been the intellectuals in Rommel's shop.

Besides the AT guns and heavy AT rifles (28/20 sPzB41), companies would also add 2x HMG (from battalion heavy company) and 3x 81mm mortar (meaning the battalion allocation was doubled), and drop the light mortars. On the whole, both AT and anti-infantry firepower was very substantially enhanced.

All the best

Andreas

All the best

Andreas

IBID

https://tacticalnotebook.substack.com/p/assault-and-battery-background/comment/42101037?r=91o16&utm_medium=ios