Headquarters and Service Companies of the Infantry Regiment (April 1942)

Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry

Welcome to the Tactical Notebook, where you will find five hundred or so tales of armies that are, armies that were, and armies that might have been. If you like what you see here, please share this article with your friends.

The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given permission to the Tactical Notebook to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. The author’s preface, as well as previously posted parts of this book, may be found via the following links:

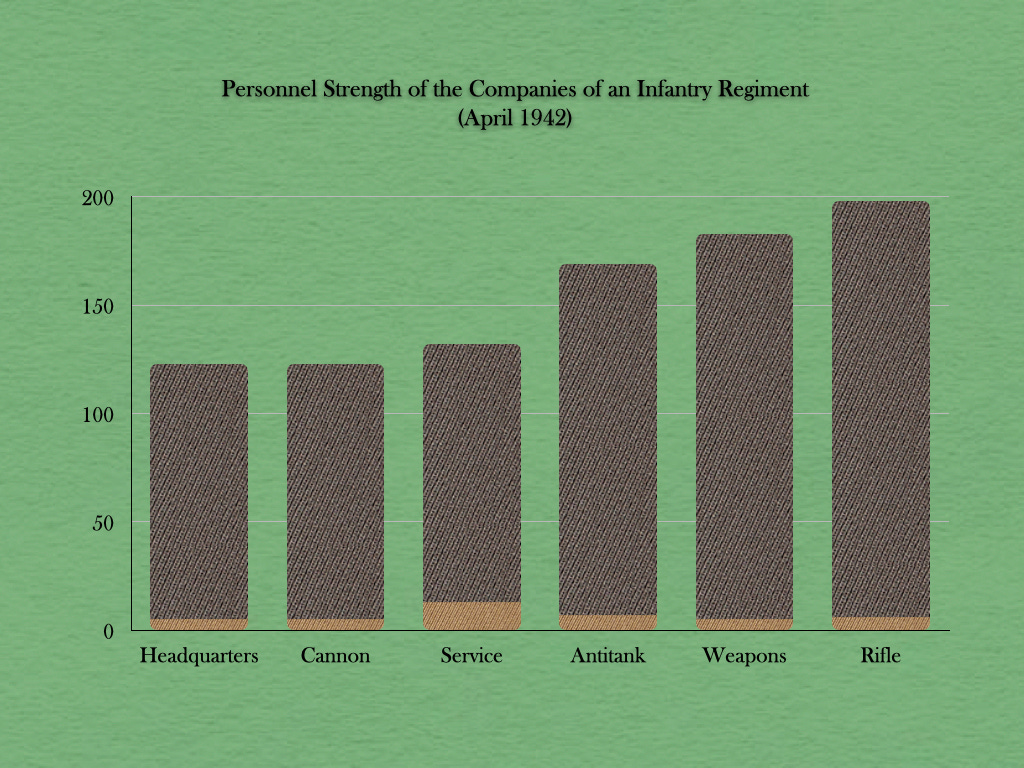

Like their immediate predecessors, the tables of organization adopted in April of 1942 provided the infantry regiment with both a headquarters company and a service company. Composed of a modest company headquarters and two platoons, each of these organizations rated as many soldiers as a cannon company, but far fewer than an anti-tank company, let alone a rifle company.

The larger of the two platoons of the headquarters company provided radio and telephone links to both the regimental headquarters and the service company. To that end, this communication platoon rated fourteen radio sets, sixteen radio operators, and twenty linemen, as well as a six-man message center and four telephone switchboards.

The smaller of the two platoons of the headquarters company assumed the functions of the intelligence platoon authorized in October of 1940. However, as much of its work involved the operation of observation posts and the conduct of patrols, it bore the more accurate designation of intelligence and reconnaissance platoon.

The headquarters of the intelligence and reconnaissance platoon consisted of one first lieutenant (platoon commander), one staff sergeant (platoon sergeant), and six privates. The latter included a driver, a radio operator, a draftsman, and two scout-observers. (The last of the six privates, designated as a “basic private,” received no specialized training.)

Each of the two reconnaissance squads weighed in at eleven men: a sergeant (squad leader), a corporal (assistant squad leader), three drivers, three scout observers, two “basic” privates, and a radio operator.

Each reconnaissance squad possessed three jeeps. As each of these had four seats, each member of each unit of that sort enjoyed the privilege of riding into battle. The platoon headquarters, however, received but one jeep. As a result, displacement required the loan of a truck from another unit, such as the transportation platoon of the service company.

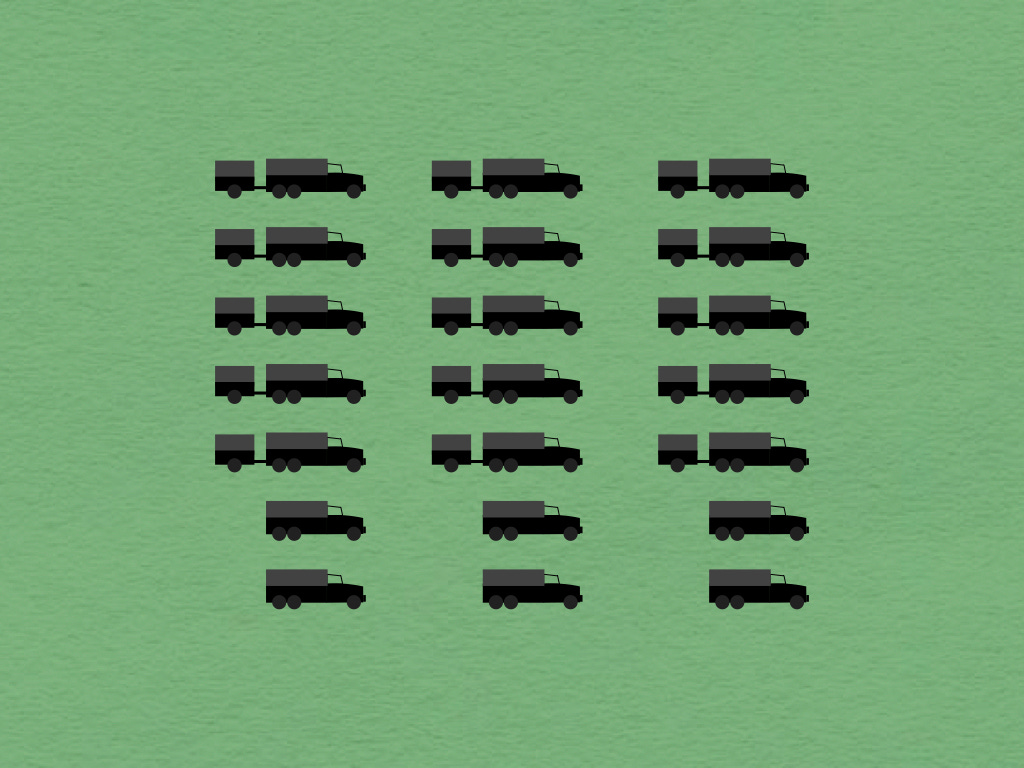

The transportation platoon consisted of a platoon headquarters and seven sections: three large battalion sections, three small company sections, and a maintenance section. The seven 2.5-ton (“deuce-and-a-half”) trucks and five 1-ton trailers of each battalion section augmented the (modest) motor transport fleet of each infantry battalion. The single 2.5-ton truck and lone 1-ton trailer of each one-man company section performed the same service for one of the three independent companies of a regiment. (As a rule, the two 2.5-ton trucks in each battalion section that lacked trailers carried ammunition, which tended to be heavier than most other loads. Those with trailers carried rations and baggage.)

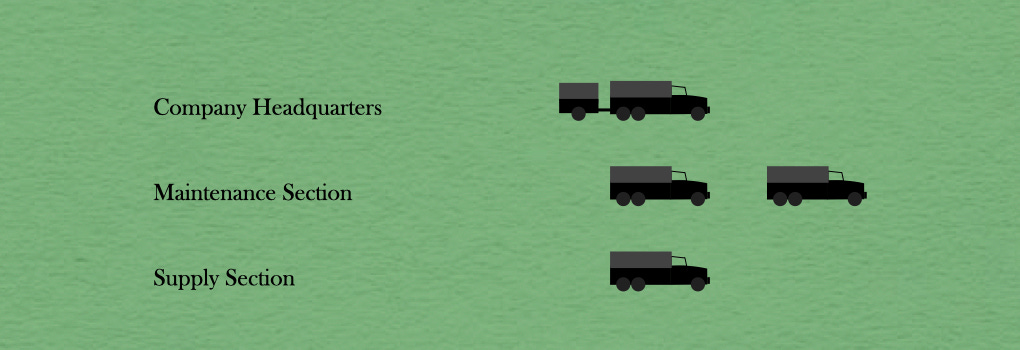

While the 2.5-ton trucks of battalion and company sections transported supplies for combatant units, those of other elements of the service company carried (and, in some cases, pulled) cargo needed for internal purposes. Thus, the trucks and trailer of the company headquarters moved items needed by the company armorer, the company cooks, and the company supply sergeant. The two trucks of the maintenance section transported spare parts, tools, and a welding outfit. The single 2.5-ton truck of the supply section of the headquarters platoon carried the equipment it needed to fulfill its definitive purpose of requesting, receiving, moving, storing, issuing, recovering, and accounting for supplies of various sorts.

In addition to the company headquarters and the supply section, the headquarters platoon possessed an organization known as the staff section. Not to be confused with the staff of the regiment as a whole (which could be found in the regimental headquarters), the staff section dealt with, among other things, matters related to manpower, mail, and morale. In keeping with that purpose, its establishment provided for a personnel officer (with the rank of captain), a special services officer (also ranking as a captain), a regimental sergeant major (in the pay grade of master sergeant), a personnel specialist (technical sergeant), four postal clerks, an athletic instructor, an entertainment director, and three chaplain’s assistants.

The staff section also provided administrative support to the regimental operations officer. This took the form of a dedicated operations sergeant (with the rank of master sergeant) and access to the services of seven secretarial specialists. (The latter, which included a stenographer and six “headquarters clerks,” provided services to the regimental headquarters as a whole.)

Strictly speaking, the commanding officer of the regiment and the eight officers of the regimental staff belonged to a separate (and very small) organization known simply as the headquarters. Thus, the structure of the headquarters company made no provision for them. Similarly, chaplains and medical personnel serving with infantry regiments maintained their membership in other organizations.

Sources:

US Army Adjutant General T/O 7-12 Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Infantry Regiment (1 April 1942)

US Army Adjutant General T/O 7-13 Service Company, Infantry Regiment (1 April 1942).

The Tactical Notebook is very fascinating to read, and it could provide a reliable source for fiction and fantasy writers in building armies.

The staff section dealt with, among other things, matters related to manpower, mail, and morale. In keeping with that purpose, its establishment provided for a personnel officer (with the rank of captain), a special services officer (also ranking as a captain), a regimental sergeant major (in the pay grade of master sergeant), a personnel specialist (technical sergeant), four postal clerks, an athletic instructor, an entertainment director, and three chaplain’s assistants.

I did not know that the personnel section had an Athletic Instructor. I mean, I never imagined that the greatest generation needed an AD in order to stay fit during combat. I figured all the walking to and from combat sights, scouting missions, etc., would have kept them fit as a fiddle.

I didn't realize that they needed postal clerks since out in the fields, I heard all they had to do was write their duty posts on an envelope and send it, but it does make sense, considering that mail was often sent back overseas to loved ones.