February 1917

Diary of a Stosstrupp Leader (Part 18)

This post continues the translation of the diary of a German soldier who fought in the First World War. Readers can find links to other posts in this series in the following guide.

1 February 1917

Catholic soldiers attended mass. From five to eight in the evening, we built barbed wire obstacles in the second line of defense, using metal screw piles. (We could not drive wooden into the frozen ground.)

2 February 1917

Everything is covered with deep snow. I went to Position B to look for Hartmann.

4 February 1917 (Sunday)

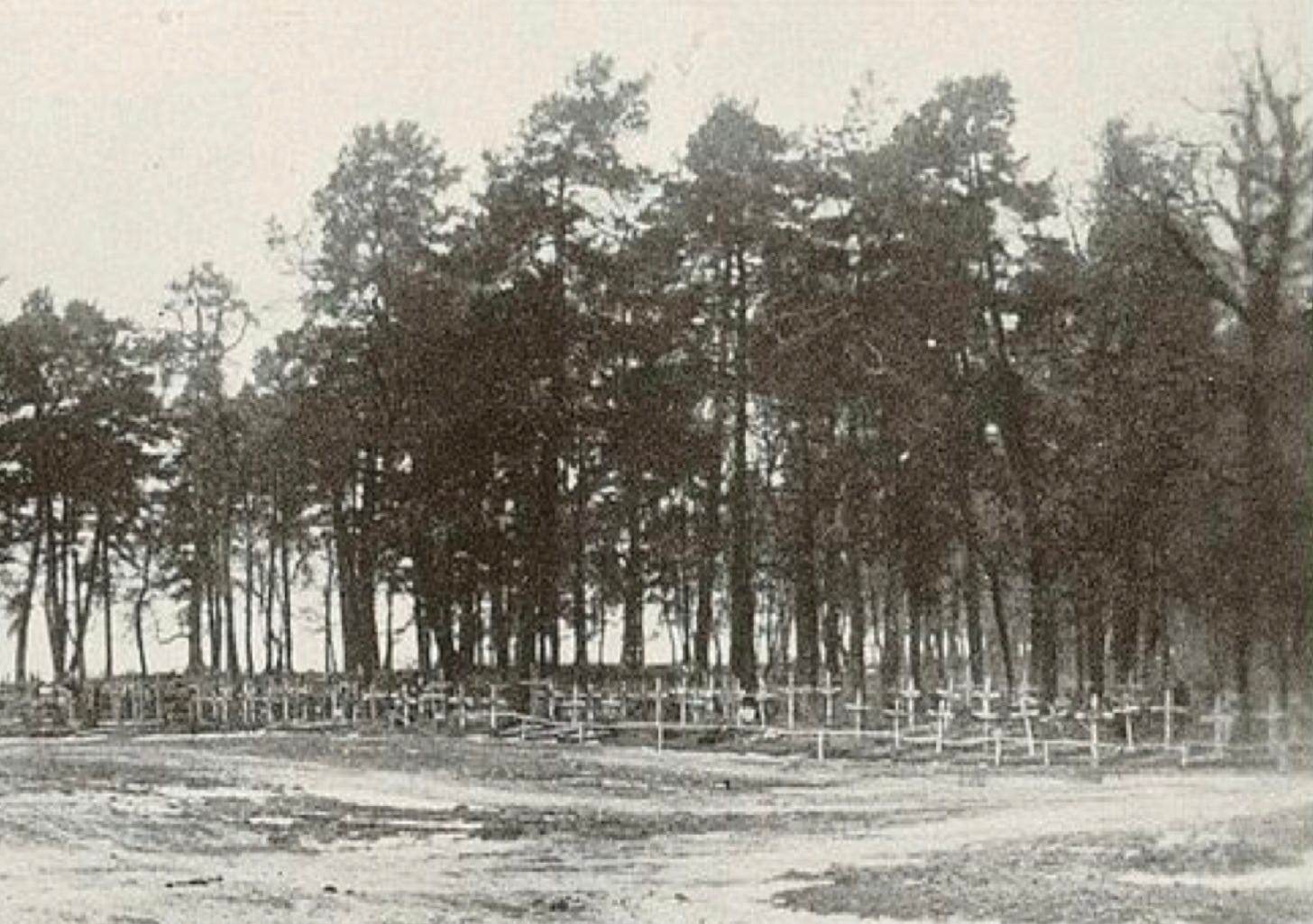

I attended a worship service in the Heroes’ Cemetery (in Zarucka Woods). Privy Councillor Cäsar presided. It was beautiful, but my legs froze.

5 February 1917

We cleaned up the second line position, shoveling great masses of snow.

6 February 1917

Lieutenant Rudloff returned from leave. At the battalion headquarters, we attended a class on gas masks. It was very cold.

8 February 1917

In the afternoon, the 8th Company, which had occupied Position B, was relieved. It was frightfully cold. I stood duty from seven in the evening until eleven at night. Once again, I took up residence in the small platoon commander’s shelter near ‘Marutschka’ the medium trench mortar.

12 February 1917

I got paid 21 marks. I fell ill, with shivering fits and a fever of 39.5 degrees (Celsius = 104 degrees Fahrenheit), which continued to rise. I was obliged to lie on the pallet in my shelter.

13 February 1917

My high fever continued. Heavy Russian artillery fire (fell on our position). The large number of explosions near my shelter suggested that the Russians were searching for Marutschka.

14 February 1917

For the first time in days I was able to stand. My legs, however, remained so weak that I could not stand duty.

15 February 1917

I stood duty from three to six in the afternoon. Then Lieutenant Winter and I went to Radcyn for a course in gas warfare. We walked fifteen kilometers in a ferocious snow storm. On the return trip, we rode in a sled.

16 February 1917

Though I felt both sick and miserable, I stood duty from three in the afternoon to seven in the evening.

17 February 1917

I stood duty from three to seven in the morning. Then I traveled, in one of the sleds of our combat trains, to Radcyn for the gas warfare course. My legs froze.

After I returned to the trenches, I stood duty from eleven in the morning to three in the afternoon.

Sunday, 18 February 1917

I continued to feel unwell.

Last night, Private Schneider shot himself in the left hand and had to be evacuated. It was a self-inflicted wound. He was a thoroughly efficient soldier, who used to sing while standing watch in the trenches.

19 February 1917

Once again a cold, raw wind blew upon us.

Two Russian deserters – big, powerful men – deserted to our side. One spoke a little German. According to him, we had been facing the St. Petersburg Guards. He also told us that our trench mortar, which the Russians had failed to locate, continued to cause them much worry.

21 February 1917

It was somewhat sunny, but still rather cold.

22 February 1917

Offizier-Stellvertreter Wennemann transferred to the 5th Company. I stood four hours of duty at night and two during the day. The temperature dropped to minus 20 degrees (Celsius = minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit).

23 February 1917

I stood duty from twelve to two overnight and from five to nine in the morning. It was hideously cold - minus 30 degrees (Celsius = minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit).

The listening posts wear shirts made of snow. In fields covered with white snow, this is the best camouflage. If, when checking posts, one forgets to call out to announce himself, he runs the risk of being shot, for the men on listening post duty shoot in the direction of sound. Each day, a new password (the name of a senior general or city) is given out. The man on watch calls out the challenge, takes his rifle off safety, and, if he doesn’t hear the password right away, shoots.

24 February 1917

I stood duty for four and a half hours overnight, and two hours. The Wolhynian fever persists. (Known in the English-speaking world as ‘trench fever’ or ‘five-day fever’, Wolhynian fever, a bacterial infection spread by lice, took its name from the province of Wolhynia.)

26 February 1917

Private Fess, one of my best men, died from a shot through the head while on duty at a listening post.

27 February 1917

Affler, Altmeyer and I made a badly-needed visit to the delousing station. The little critters make it very hard to sleep. When we are outside in the cold, they keep still. But when we return to our warm shelters, the rebellion begins anew.

Lieutenant Winter returned from the machine gun course. The quality of rations fell. We were hungry!

28 February 1917

The frightful cold has relented, but fresh snow has fallen. I stood two hours of duty over the night and four hours during the day. It was my eightieth day in the trenches. We hear rumors that the system of regular reliefs will end.

to be continued …

Sources

The text comes from Alwin Lydding Meine Kriegstagbuch (My War Diary), an unpublished manuscript that I found at the Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archive) (Folder N 382/1).

The photo comes from the regimental history of the Reserve Infantry Regiment 265, a unit that, like Infantry Regiment 97 and Infantry Regiment 137, served in the 108th Infantry Division during the last three years of the First World War. W. Walther Das Reserve-Infanterie-Regiment 265 in Angriff und Abwehr 1914-1918 (Reserve Infantry Regiment 265 in Attack and Defense) (Zeulenroda: Bernhard Sporn, 1933)

These snapshots in time. The little peek into a day in the life. These things make you wonder what each of these soldiers were really like. What the liked and disliked. What books they read, and what was family life like. I am humbled when I read the diary entries.

What a miserable war.