Counter-Battery Fire

Tactics Made Simple

The artillery of Europe entered the 20th century under the shadow of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. The chief lesson of that conflict, most gunners in most places seemed to agree, was that the artillery played two roles in battle. Its first job was to knock out the enemy artillery. Once that was accomplished, the artillery would take of the task of combatting enemy infantry.

In 1870, locating enemy batteries was an easy task. Given the relatively short (2,000-4,000 meters) ranges of field pieces and widespread ignorance of indirect fire techniques, batteries almost always fired from exposed positions. That is to say, while the horses might be hidden in a hollow or behind a ridge, the guns themselves were loaded, aimed, and fired in plain view of the enemy.

The duel between the German and French artilleries that preceded the big battles was thus a duel in a very real sense. Without the complication of cover, only two considerations were important. The first was the quality of the weapons. The second was the skill of the crews. In 1870, the Germans won “hands down ” in both departments.

In 1914, during the opening campaigns of a conflict that struck many as the Second Franco-Prussian War, this relationship was reversed. It was now the turn of the French artillery to go to war with superior guns served by superior crews formed into better batteries commanded by more technically proficient officers.

As a result, when French and German batteries faced each other in the open, the French were generally able to get the better of their opponents. Consider, for example, the following description of a contest between a single French 75mm gun and a battery of six German 77mm guns.

“A French piece fires on a hostile battery. The cloud of smoke having passed away, our officers look with a spy-glass on the effects of their fire and discover with astonishment that the enemy artillery servers are fixed at their places. Later they discover that it is the immobility of death. ”

While such events were certainly extraordinary, the power of the French artillery was such that the Germans soon learned the value of hiding their guns behind hills and firing indirectly. French gunners, who had shown great interest in this technique before the war, also began to do the same.

From the point of view of armament, this should have given the advantage to the Germans. It was the Germans, after all, who had entered the war with the most powerful force of light and heavy howitzers in the world. Indeed, a belief that French batteries would resort to indirect fire played a big role in the German decision to acquire its large (and expensive) collection of 105mm and 150mm howitzers.

In a series of experiments conducted before the war, officers of the German heavy artillery branch discovered that a battery of four heavy field (150mm) howitzers firing 80 to 100 rounds at a simulated French field gun battery would easily knock that battery out of action. A target battery located within a rectangle that was about 100 meters wide and 400 meters deep, for example, would lose 30 to 50% of its personnel and 60 to 65% of its guns, carriages, caissons, and other material.

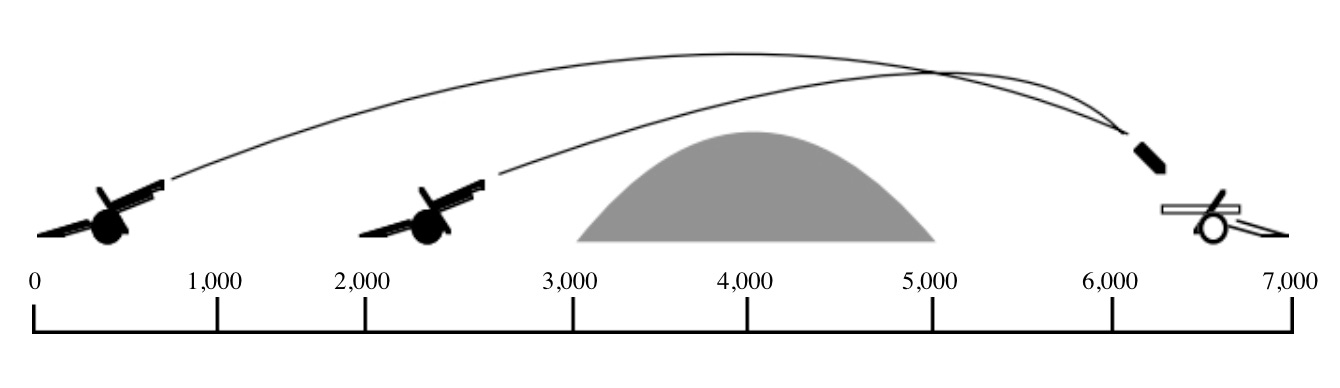

What the experiment did not show, however, was the difficulty that one side would have locating the enemy battery with the necessary degree of precision. Given that field guns could effectively fire at ranges out to 5,000 or even 6,500 meters, a shell passing over a ridge might come from a gun located just behind the ridge, 3,000 meters behind the ridge, or anywhere in between.

Sources:

Frédéric Georges Herr, L’Artillerie, Ce Qu’elle a Été, Ce Qu’elle Est, Ce Qu’elle doit Etre (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1924)

Maurice Duval, “Comparison Between the German ‘77 ’ and the French ‘75’”, The Field Artillery Journal, 1917, pages 425-6