Bombarding Coyotepe

USMC Field Artillery in Nicaragua in 1912

The following account comes from an article published the Field Artillery Journal in 1915. The author, Captain Robert O. Underwood of the US Marine Corps, commanded the field artillery company that served with the American expeditionary force in Nicaragua in 1912.

Comments made by the editor appear within brackets.

Until 1912, the Marine expeditionary forces generally depended upon the rifle and the machine guns as their weapons for use in the field except in one instance in the Philippines one company was at one time in the possession of our obsolete Navy landing guns, and in China in 1900, a company used this type of gun in the engagements around Tientsin, until the entire lot of ammunition was expended, when their further use on this occasion was abandoned.

As a means of transportation for this artillery, the men used drag ropes, and with the twenty-four rounds of ammunition carried on the field piece, it is apparent that it could not have operated at any distance from a railroad, and, therefore, could not have been considered a serious factor.

The assignment of the advance base work to the Marines and the increased importance of the character of expeditionary duty required of them, where on different occasions they have been sent miles into the heart of Central American countries and placed in positions where they were dependent upon their own resources has imposed a new condition upon them. The revolutionary forces, whose actions the Marines at any moment might have had occasion to dispute, had begun to obtain modern artillery and to utilize the services of foreigners to serve it.

These conditions found the Marines in a position where they could no longer depend upon the rifle entirely, and in 1912 when an expedition was sent to Cuba as a consequence of the disturbed conditions in the Province of Oriente, one company was provided with two field pieces of Mark VII landing gun type, which had been recently adopted by the Navy Department. [Designed by the German firm of Rheinmetall, this piece bore a close resemblance to the 3-inch guns adopted by the US Army in 1902, 1904, and 1904.]

The officers and men attached to this company had received very little, if any, instruction and training in the use of artillery, and the guns were never fired during this expedition. It is supposed that the moral effect their presence in the district produced was sufficient to keep the insurrectos at a distance. I was informed by the officer commanding that company that his district was much less frequented by insurrectos than any of the others.

In 1910, the Advance Base School was organized and located at New London, Conn. Its object was to give officers both practical and theoretical instruction in subjects which would enable them to carry on successfully the new work assigned them.

The study of field artillery was embraced in the course, and it included the study of field artillery drill regulations and the handbook on 3-inch gun material. During the first year no practical instruction was possible, as only the books were furnished. The same course was pursued in 1911, with a new class of officers, those of the previous year being assigned to other duty.

The practical work for this year included several map problems, and one or two days in the calculation of firing data. Those students who were found qualified to solve one of these problems were considered quite proficient in artillery. More practical work would have been included in the course had it been possible to have secured the necessary in-instruments and field pieces. The ordinary mind does not retain dry book rules and descriptions of instruments sufficiently long to be of much practical value, as will be seen later on.

In August, 1912, a regiment was hastily assembled at Philadelphia, and embarked for duty in Nicaragua. As I had completed the course in artillery, and had succeeded after much tedious painstaking work in solving a few problems in firing data. I was assigned to the command of the company with the field pieces. Neither of the two junior officers of this company had ever used a field piece, and none of the men had any knowledge of guns. With these inexperienced officers and men, the usual battery instruments, and 200 rounds of ammunition. I found it a difficult problem indeed, to recall a sufficient amount of my book knowledge and in a few days produce a practical fighting unit.

From the date of embarkation on this expedition, 22 August 1912 until 3 October 1912, when the defenses of La Baranca and Coyotepe were bombarded, assaulted and captured, there was scarcely any opportunity offered to train the company to serve modern field pieces efficiently. My hastily organized company was constantly being split up for guard details, and previous to the bombardment, not a single drill was held where each man was taught his individual duty which he might have in action in this machine. No one in the company had ever fired a shrapnel [shell] and were very naturally disappointed to find that their action was not as prescribed in the regulations strictly, and were much at sea for a while what to do when shell after shell was fired and lost.

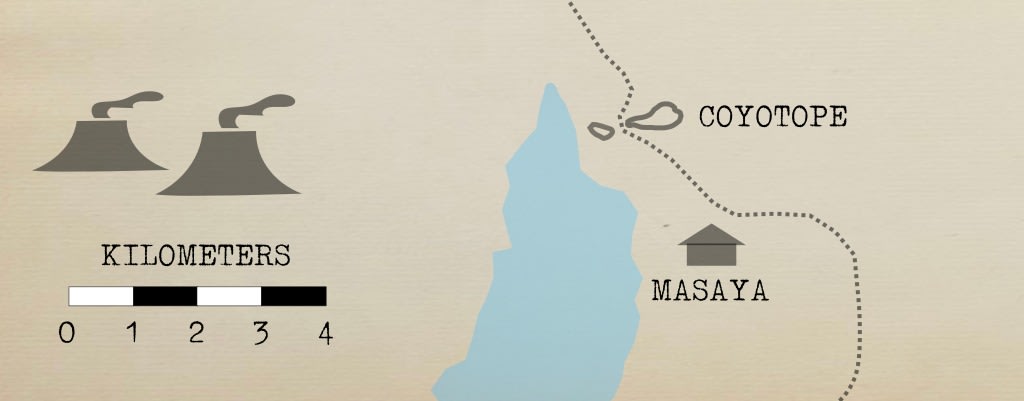

Coyotepe and La Baranca, two positions which commanded the city of Masaya were considered by the Nicaraguenses impregnable, and had never been captured. The railroad from Managua to Granada ran between these two hills, and Masaya lay on the side toward Granada.

General [Benjamin] Zeledón, who commanded all the rebel forces in possession of these hills and the city of Masaya, had his headquarters on Coyotepe. The latter hill was rather precipitous and difficult to climb. Barbed wire entanglements had been provided and the position fairly well intrenched. The character of trench was generally deep and narrow, and partially provided with traverses for protection against flank fire. The top of the hill contained a trench which extended completely around it. The wire entanglements were located below the lower line of trenches.

The upper trench or parapet was occupied by a portion of the infantry, several machine guns, one 3-inch gun with a range of 8,000 meters, and several 1-pounders which were very obsolete.

La Baranca contained two redoubts for infantry, and with two 3-inch field pieces, one redoubt for infantry, and one machine gun, with a series of small rifle pits very poorly constructed for infantry.

A ridge extending from Coyotepe toward La Baranca, also commanding the railroad, was defended by two more 1-pounders, one machine gun and infantry. There were no entanglements in front of this ridge.

The tense situation in Granada, 25 miles south of Masaya, demanded the presence of Marines, so accordingly Major [Smedley Darlington] Butler’s battalion was dispatched there. When his train reached a point about 3,000 yards from Coyotepe, between the Federal and rebel lines, it was fired upon by the artillery from Coyotepe. It was then decided to force a passage. Two more battalions were brought up from Managua, and the company of field artillery [the author’s company] from Leon.

The two guns which had been attached to Major Butler’s battalion were added to my company. All the guns were brought up on the train within two miles of the position selected for the artillery, there disembarked from the train, ox teams hired from the federal forces, and then they were hauled into position about 2,600 yards [2,378 meters] from Coyotepe and 1,800 yards [1,646 meters] from La Baranca.

When all the details for the attack had been completed, word was sent to General Zeledón that his position would be bombarded unless our troops were permitted to pass on to Granada unmolested. After considering our numerical superiority, and after much customary discussion characteristic of all Latin-American people, he finally agreed not to molest the passage of American troops, nor to interfere with the operation of the railroad. Our troops then withdrew.

With respect to the railroad, the agreement was soon broken, and it became necessary to dislodge these rebel forces from the menacing position they were occupying. On the afternoon of 2 October 1912 our forces occupied the same positions they had previously occupied.

The bombardment was ordered to begin at 8 o’clock on the following morning, provided the rebel forces had not in the meantime complied with our demands.

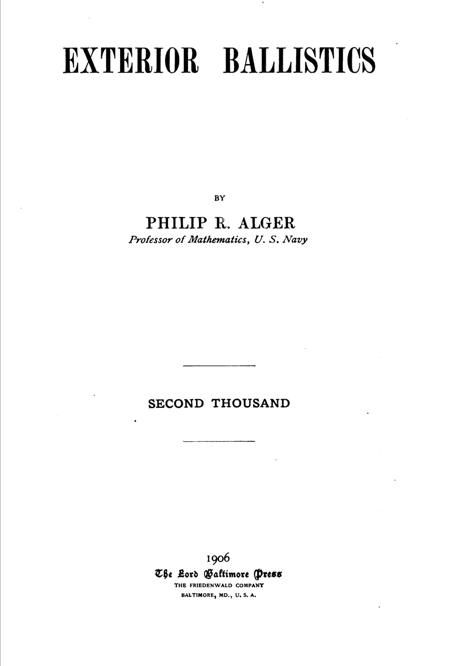

The method of fire employed for adjustment was by piece with timed fire. I was not long in discovering that this method was quite impracticable, with a range table for the time of flight which I had, with the assistance of several officers, worked out from Alger’s Ballistics on the way down on board the transport; with only an improvised fuse punch, which was imperfect in its results; and with only book knowledge to guide me in making observations and applying corrections.

Direction was easily obtained, but the imperfect action of the fuses so completely confused me that this method was very shortly abandoned, and an effort made to adjust by percussion. This method also proved to be a failure as the shots going over the position could not be observed and those falling short were lost in the high grass and bushes in the proximity of the near side of the target.

There was not sufficient ammunition to expend more in these fruitless attempts to adjust the fire on the narrow barren strip of earth on top of Coyotepe where the trenches were located, by this method. Percussion effect of these shells for observation was found to be small, and an examination of the ground after the engagement showed that some of the shells had not functioned on impact, only burying themselves in the ground. At this hour, the sun was directly in our eyes, and the side of the target towards us was very dark, which two features contributed further to the difficulty of adjustment.

La Baranca being a barren hill, observation by percussion was possible. A few shots directed at the defenses here caused the occupants to desert their positions, and it appeared that they never again returned. The field pieces and machine guns were the principal targets, but our shells only tore up their earth-work defenses, and frightened the occupants away.

Coyotepe was again bombarded during the afternoon, and fire adjusted on the trenches by percussion. This was made possible by the target being lighted up by a change of position of the sun and the experience gained during the day. The battery position enabled the fire to enfilade the principal trench and some effect was obtained by percussion fire.

In the forenoon, the rebels moved about their positions quite leisurely without any apparent fear of our fire, but during the afternoon they stuck closely to their trenches, and only moved when compelled to do so by the effect of the fire upon their trenches. There was considerable confusion amongst them on several occasions, in their endeavor to seek cover elsewhere, when their main trench was enfiladed. They were again surprised to find that their new position some 50 yards away from the main trench was quite as dangerous. The majority of the rebels then sought cover on the reverse slope of the hill and it was reported that many of them returned to Masaya.

Both direct and indirect laying were used, but much better results were obtained when using indirect laying even when the target could be seen plainly. The difficulty of pointing out to each gunner the exact point where his aim should rest on the lines of trenches occupied by the rebels, and keeping him on that same point in subsequent firing for close adjustment was realized practically when after firing a number of shots dispersion in both range and direction added to the already long list of difficulties. In some parts of the line for a distance of 50 yards or more, the trenches would present such a sameness of appearance that it was found not only a difficult task, but a waste of considerable time to indicate to the gunners their point of aim.

During the night of the third of October, shots were fired at intervals with previously obtained data at the trenches on Coyotepe, while the infantry was moving into position for the assault on the early morning of the next day. A smothered lantern hung close in rear of the gun, served as an aiming point. The bursting shell illuminates the targets very little at night.

Owing to the faulty ammunition, poor implements for handling it, and the absence of reliable communication between the infantry and the artillery, the infantry received no support from the artillery.

Had it been possible for the artillery to have cooperated with the infantry on this occasion, it is believed that nearly all opposition directed against our forces could have been forestalled by shrapnel used with either time or percussion fire. When the infantry assault began, although it was too dark to distinguish between friend and enemy, I could plainly see the rebels rising from the trenches they had abandoned the previous day, and had again occupied during the night, to fire their rifles and machine guns at our troops as they advanced toward the position. It occurs to me that in such a position as this, it is the artilleryman’s duty to act without orders, but in this particular instance faulty ammunition and the absence of reliable communication would have made it a very hazardous undertaking.

Even in this little engagement where we were only a couple of thousand yards distant from the enemy, an experienced artillery officer near the infantry in direct communication with the artillery would not only have been helpful in aiding observation, but would have been invaluable in keeping the artillery informed of the location of our troops, and informing the artillery when its own fire was becoming dangerous to our troops.

One company advanced up a ravine and they could not possibly have been seen by me until they had arrived within a very few yards of the enemy’s position. It was remarkable the way the occupants of Coyotepe fought to the very end in face of certain death.

During the assault, a small field piece which was concealed in rear of the slope running from Coyotepe to La Baranca was run up into position, and opened up a rapid fire at the hospital train approaching the position it was ordered to take to receive the wounded. At a range of 1,700 yards with previously obtained data, two shots were sufficient to cause its gunners to abandon it. But for this timely action the hospital train might have suffered considerable damage or been destroyed.

At the capture of León [on 6 October 1912], the artillery did not come into the action which resulted upon the occupation of the city. It occupied a position, however, for the purpose of bombarding the fort outside the city, and to watch church towers where it was known snipers were located. No action resulted as the garrison surrendered to our forces the following morning after the city surrendered.

In this campaign, the actions which occurred were on or near railroads, and the artillery was loaded on flat cars for transportation for great distances. When it became necessary to occupy a position too distant from the point of disembarkation from the train to the place to be occupied for the attack for the guns to be hauled into position by man-power, yokes of oxen were procured and the yoke lashed to the limber pole. Two yoke were found to be sufficient to haul our gun and limber weighing 5,500 pounds, but at a very slow pace. If it had ever become necessary to maneuver for any purpose it would have been quite impossible.

This little action taught us its lesson. It showed very clearly that Marines should have mobile and well-trained artillery to accompany them on their expeditionary work; that they must be provided with efficient material; and that its officers and men must be thoroughly trained in its use to obtain its maximum effect.

Source

R.O. Underwood ‘United States Marine Corps Field Artillery’ Field Artillery Journal (April-June 1915) pages 297-305

Related Reading

😲 It is actually amazing that they were able to function as a supporting Artillery unit at all given the handicaps placed on them. And this folks is why the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill, OK is a joint Army and Marine Corps training facility.