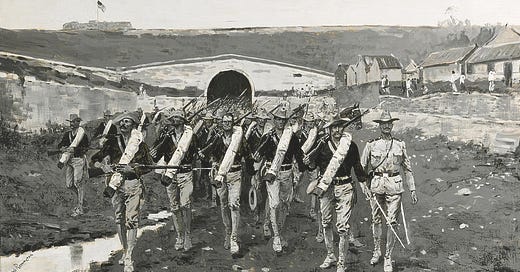

The Organization of the US Army (1898-1905)

Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry

The estate of the late John Sayen has graciously given the Tactical Notebook permission to serialize his study of the organizational evolution of American infantry battalions. Links to other parts of this book can be found with the help of the following guides:

The war with Spain exposed a lot of American shortcomings and logistics ranked high among them. The movement of supplies had been largely entrusted to hired civilians who had proven very unreliable. The loading and unloading of Shafter’s ships had been totally disorganized. Shafter’s men were ravaged by disease after Santiago fell, due in no small degree to poor sanitation and the low priority assigned to medical supplies. Disease also attacked many soldiers who never left the United States. Although the troops had evinced plenty of courage and enthusiasm, their officers were often incompetent and their weapons inferior even to those of a third-rate power like Spain. Cooperation between the Army and Navy was unsatisfactory, as there was no effective joint command.[1]

Nevertheless, Spain’s defeat had created a substantial American colonial empire almost overnight. The United States would occupy Cuba but would annex Puerto Rico, the Hawaiian Islands, and the Philippines. Native Filipinos, however, demanded immediate independence and proceeded to launch a rebellion of a scope and intensity for which even the Army’s recent experiences against the Plains Indians left it unprepared. With all its newfound commitments, the Army soon discovered that it needed more men to keep the peace than to fight the war. However, no sooner had peace with Spain been concluded that the Volunteers began clamoring to go home as loudly as they had previously demanded to be called up. While the Volunteer regiments in the Philippines agreed to stay on long enough for replacements to arrive, Congress was forced to maintain the Regular Army at 65,000 men and to reinforce it with 35,000 Volunteers (all federally recruited this time) who would serve until 1901. These men would form 24 infantry regiments (numbered 26 through 49), plus a cavalry regiment and a regimental-sized signal corps. Ironically, this produced essentially the same 100,000 man Army that the original Hull Bill had called for. In addition, the Army created an unnumbered two-battalion Puerto Rican Regiment in 1899. Unlike the 24 volunteer regiments, however, this would be a permanent addition to the Army. The authorized enlisted strength of a standard three-battalion infantry regiment increased to 1,378. This included the provision of trained cooks for the rifle companies to address complaints about the poorly prepared food being served by company messes.[2]

Unlike later eras in which an easy military victory would be treated as cause for complacency, the Spanish American War spurred the Army to implement numerous reforms concomitant with the 1901 appointment of Elihu Root as Secretary of War. Root was a lawyer with no prior military experience. His immediate predecessors had all been Civil War veterans. He did, however, have a genuine desire to improve the Army and his mind was not burdened by a lot of preconceived ideas. He soon came under the influence of the Uptonians who urged him to form a general staff on the Prussian model, increase the professional education of officers, and to rely on Federally recruited volunteers as a wartime reserve rather than the National Guard.[3]

Meanwhile, in order to replace the 35,000 US Volunteers whose service was to expire in 1901, the National Defense Act of May 1901 authorized five new Regular Army infantry regiments (numbered 25 through 30). In the Philippines, the Army had already discovered the value of native scouts and guides for fighting insurgents. As a result, the Army had actively recruited such men into unofficial companies under American officers, and paid them as civil employees of the Quartermaster Department. The 1901 Act legalized 50 companies of what became known as the Philippine Scouts. Besides augmenting the infantry, the 1901 Act also made substantial increases to the Regular Army’s cavalry, artillery and engineers. It allowed the president to vary the total enlisted strength of the Army between 59,000 and 100,000; or the enlisted strength of a rifle company to between 65 and 150 enlisted; or that of a regiment to between 816 and 1,836 enlisted. About 3,800 officers were also authorized (an increase of 1,300). Although the maximum strength levels were intended for formations stationed in combat zones like the Philippines, casualties and recruitment shortfalls tended to keep such units at close to their minimum strength levels.[4]

The next order of business was the National Guard. Root was enough of a politician to realize that, whether the Uptonians liked it or not, the Guard was there to stay. He believed that the best way to deal with it would be to transform it into something that could actually play the wartime role that its political power had secured for it. An Act passed in 1903 reduced the number of National Guard infantry regiments from 155 to 129 in order to provide much needed increases in its cavalry and artillery. More money for training and equipment would follow.[5]

Apart from incremental improvements to its organization, the Army would make major changes to its weapons and equipment. The Krag-Jörgensen rifle, upon whose acquisition so much time and energy had been lavished, had been tried and found wanting. Yet, in 1900 Root strong-armed the Navy and Marine Corps into replace their Lee rifles with Krags in the interest of standardization. However, Root also directed the Army Ordnance Department to replace the Krags with a Mauser rifle similar to the one the Spaniards had used so effectively. This became the highly successful Springfield M1903. Popular with the troops, it was sturdy and its accuracy made it highly prized in an Army that placed a heavy emphasis on individual marksmanship. Although the Regulars received the new rifle fairly quickly, rearmament of the National Guard dragged on for years. Some Guard regiments could not even get rid of their Springfield “trap doors” until as late as 1905 when they finally received Krags.[6]

Editor’s Note: The format of the many appendices to this work fit poorly with Substack. For that reason, I have placed them on a PDF file that can be found at Military Learning Library, a website that I maintain.

[1] Weigley pp. 307-312; Cosmas pp. 245-294.

[2] Mahon & Danysh p 36; John K. Mahon pp. 29-30; Urwin pp. 143-148; Weigley pp. 307-312. Each infantry regiment strengthened its 12 rifle companies with six men each but dropped its three battalion quartermaster sergeants.

[3] Weigley pp. 314-317.

[4] Mahon & Danysh pp. 36-38; Urwin points out on page 145 that, for example, Company C 9th Infantry when it was destroyed in the infamous “Balangiga Massacre” on 28 September 1901 on Samar had all three of its officers but only 72 of its 150 authorized enlisted men present and fit for duty. On 28 July 1900, the 9th Infantry had sailed from the Philippines for China with a reported strength with 37 officers (four medical) and 1,241 men (Correspondence p 419). A battalion (four companies) of the 15th Infantry embarking for China at San Francisco on 2 August 1900 it reported a total strength of 13 officers and 512 men (Correspondence p 443).

[5] Weigley pp. 317-319; Urwin pp. 148-150; Mahon & Danysh pp. 36-38.

[6] Weigley pp. 318-319 & 324. Smith pp. 64-65; and Heinl op cit p. 150.