On 22 April 2023, Michel Goya posted a piece (“Assault on Zapo”) that described the forces that, in his view, would be involved in a Ukrainian attempt to breakthrough the Russian defenses in Zaporizhzhia. Located east of the last great bend in the Dnipro River and west of the breakaway republics of the Donbas, the Russian position in this region lacks many of the natural advantages enjoyed by its counterparts in other sectors. It thus struck Colonel Goya as “the most likely zone of attack.”

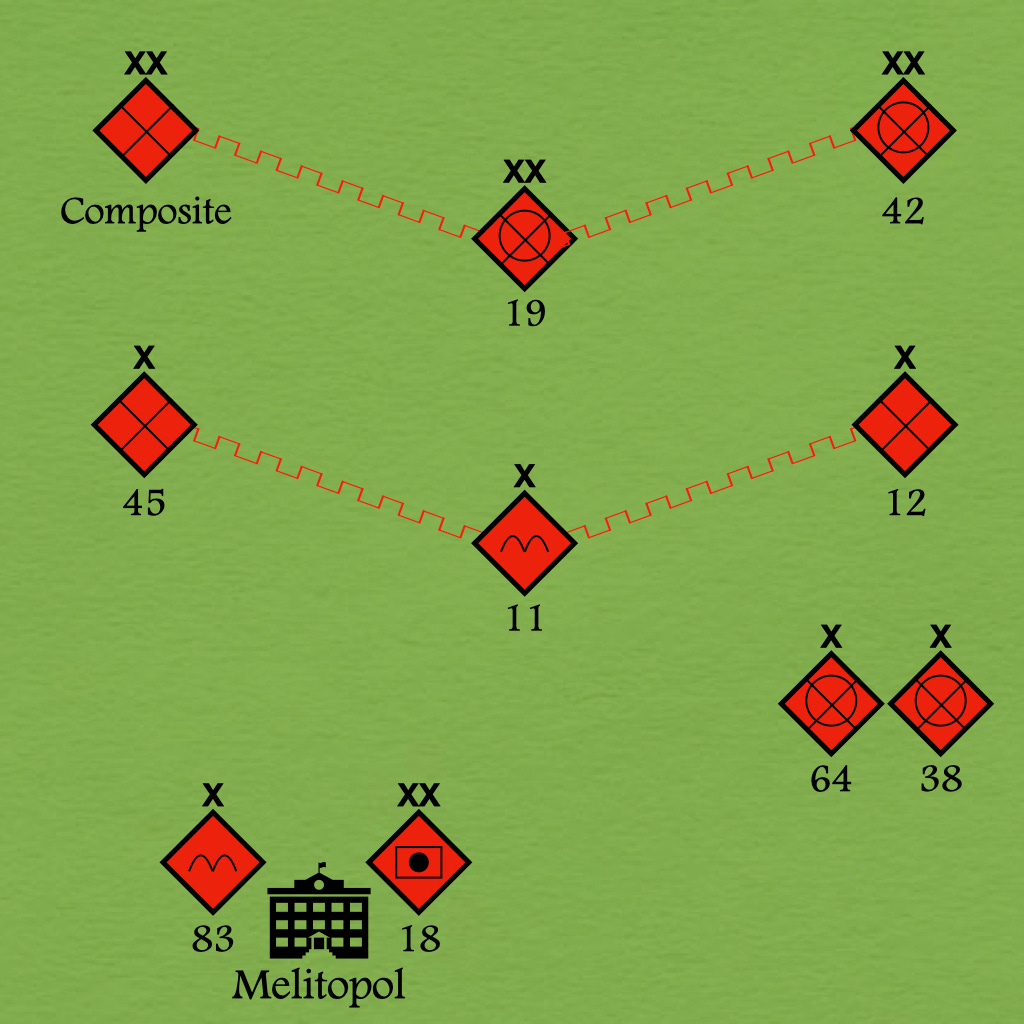

The Russian position in “Zapo” consists of a forward line of three divisions, a second line of three brigades, a reaction force, and the garrison of the city of Melitopol.

Two of the divisions, the 19th and 42nd Motorized Rifle Divisions, are regular formations of the Russian Army. The third, however, was created by combining elements of the Wagner Organization with units of the militia of the Donetsk People’s Republic.

Of the three brigades of the second line, two are special forces units that have been reconfigured to serve as infantry. The third is an airborne brigade.

The reaction force, under the command of the headquarters of the 35th Army, consists of two motorized rifle brigades.

The garrison of Melitopol, which was one of the first cities occupied by Russian forces at the start of the “special military operation”, consists of an airborne brigade and the one-of-a-kind 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division. Designed for the defense of the Kuril Islands, this all-professional formation is well supplied with field artillery, anti-aircraft artillery, and tanks. (You can find equipment lists and detailed orders of battle on the Russian and Ukrainian versions of the Wikipedia article on the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division.)

As imagined by Goya, a Ukrainian offensive in Zaporizhzhia would begin with long-range fires. Carried out by ground-attack aircraft, helicopters, missiles, drones, and long-range artillery units, these would be aimed at “bases, command posts, depots, the flow of supplies, et cetera” in order to “interdict, or, at least, hamper” the movement of Russian forces behind the front lines.

Goya entertained the possibility that raids conducted by commandos or partisans might play a role in the program of long-range fires. However, after considering the density of the Russian forces in Zaporizhzhia, the openness of much of the ground, and the situation faced by the civilian population, he came to the conclusion that the Ukrainian forces would conduct few, if any, operations of that sort.

As befits a scholar of the First World War, Goya imagined that the attack upon the front line would begin with a ferocious artillery bombardment. This, he explained, would serve to neutralize the defenders, destroy some of the obstacles, and prevent the movement of local reserves.

In the wake of this “storm of steel,” Ukrainian sappers would, slowly and systematically, clear paths in the obstacle belt. As they did this, other men on foot would feel their way forward, looking for routes that would allow them to pass between surviving strong points, which they would then attack from the rear. (Where such vehicles were available, these infiltrators would cooperate with the heaviest of the armored vehicles in the Ukrainian inventory.)

This process of “blast and burn, sneak and turn” would necessarily take a good deal of time. (Goya describes a rate of advance of one hundred meters an hour as “lightning-like.”) Thus, the Russians would have time to bring up some of the many units that they keep in reserve, whether to conduct counter-attacks or to take up new defensive positions behind the existing line. (The 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division would be well suited for both missions, especially when reinforced by the two motorized rifle brigades in reserve.)

Goya wraps up his thought experiment by laying out a number of possible outcomes. If the Ukrainians succeeded to tearing substantial holes in the first Russian line, they might liberate the towns of Vassylivka, Tokmat, and Pohlohy. If they broke through, they might take control of the nuclear power station at Enerhodar or reach the outskirts of Melitopol. Such victories, he concludes, would be impressive, but far from decisive.