Artillery in the Boer War (Part III)

Edwardian Armies

The British Empire won the Boer War. Perhaps because the war had not been the walkover that everyone had expected or perhaps because the war coincided with a flowering of British military professionalism, the British army soon embarked on a thorough reexamination of their way of doing business. For the infantry, this meant a dramatic increase in the emphasis placed on rifle marksmanship and field craft. For the artillery, there was a complete rearmament and a total revision of regulations.

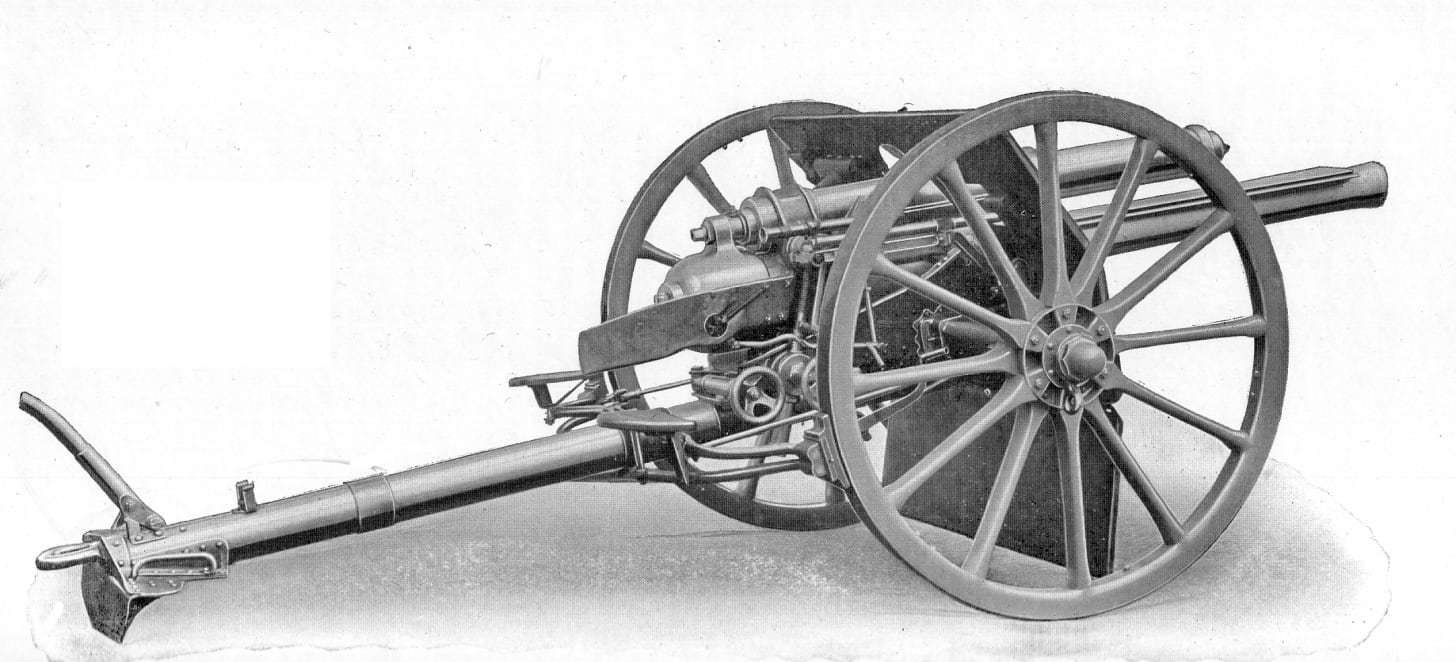

The artillery pieces adopted by the British Army in the decade following 1902 possessed characteristics that would have been of great value in South Africa. In particular, the shells fired by these guns and howitzers were much heavier than those used with their foreign counterparts. Thus, the most numerous weapon in the new British artillery park, the 18-pounder field gun, fired a shell that weighed 8.4 kilograms. This was much heavier than the second largest field gun projectile in front-line service at the time, the 7.24 kilogram shell fired by the Model 1897 75mm gun of the French Army.

The published doctrine of the British artillery, likewise, owed much to lessons gleaned from fighting the Boers. Regulations dealing with the defense flattered the Boers with almost complete imitation. If the enemy had a superiority of artillery, they advised, guns were to be dispersed along the infantry firing line as batteries (of six guns) or sections (of two guns). These guns should be so placed as to take advantage of opportunities for taking the attackers in the flank, to enfilade their advancing skirmish lines, or to place the attackers in a cross fire.

If, however, the British were the ones with the superior artillery, the field guns were to be massed. In the attack, these massed guns should concentrate their fire on that section of the enemy line where the infantry planned to attack. This fire should remain on that line until the infantry got so close that there was danger of their being hit by “friendly fire.” At that point, the fire should be shifted to the rear of the enemy position to prevent the enemy from reinforcing his line.

The enemy artillery was no longer the primary target of attacking guns. There was to be no “artillery duel” preceding the infantry attack. If, however, the enemy artillery posed a danger to the infantry attack, it was to be fired on. And if the enemy artillery fired on the British artillery, the British artillery was not to try to hide itself, rather it was to keep firing so as to keep the pressure of off the attacking infantry.

Sources:

John P. Wisser, The Second Boer War, 1899-1900 (Kansas City, Mo: Hudson- Kimberly Publishing Company, 1901)

E. S. May, Field Artillery with Other Arms (London: Samson, Low, Marston, and Company, 1898)

Prussia. General Staff. Historical Section. (W. H. H. Waters, translator), The War in South Africa (London: John Murray, 1907)

P. Van Berchem (William Lassiter translator), “Notes on the Artillery in the South African War” in War Department, General Staff, Selected Translations Pertaining to the Boer War, April 1, 1905 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1905)

Darrell D. Hall, “Guns in South Africa 1899-1902” Military History Journal, Volume 2 (1971), Numbers 1, 2, and 3

Great piece! Depite Wisser's prescient observations, the US Army was unmoved by the experience of artillery in the 2nd Boer War. Not until after the Russo-Japanese War did we start to rethink the problem.