A Visit from the Kaiser

22 December 1917

Shortly before the fourth Christmas of the First World War, Kaiser Wilhelm II celebrated the recent success of the counter-offensive at Cambrai with a formal visit to some of the formations that had won that victory.

On the next day, in bitter frost, cargo trucks took us to the base near Solesmes [some twenty kilometers east of Cambrai). When we came to a hill, we had to get out and push the trucks, and place blocks under the wheels with their iron tires, because the roads were covered with ice. Near the little town of Solesmes was a large airfield, where aircraft of Richthofen’s squadron, which had just taken to the skies, made circles in the air, and some twenty-five detachments, each drawn from a different division, were formed up in a large square. It was December 22, 1917.

Around 11:30 in the morning, the blasting of sirens announced the arrival of the Kaiser. We greeted him with a hurricane of hurrahs.

‘Ah … ten … SHUN!’

In icy silence, the men in the detachments stood perfectly still. A drum roll rumbled across the open field, competing with the rhythm of our steps, as we marched, clinking like silver, in front of the Kaiser. With roaring engines, aircraft, lined up in neat rows, swam into the skies above us.

We felt a shiver, a sense of our power, and a joyful recognition of German greatness. This is us … us! How long has it been since we felt this way! Then the music surges into the blood, the drumbeat straightens the rheumatic bones, bent crooked by front-line service, and lifts the weary, drooping heads so that the chest swells and new air fills our lungs.

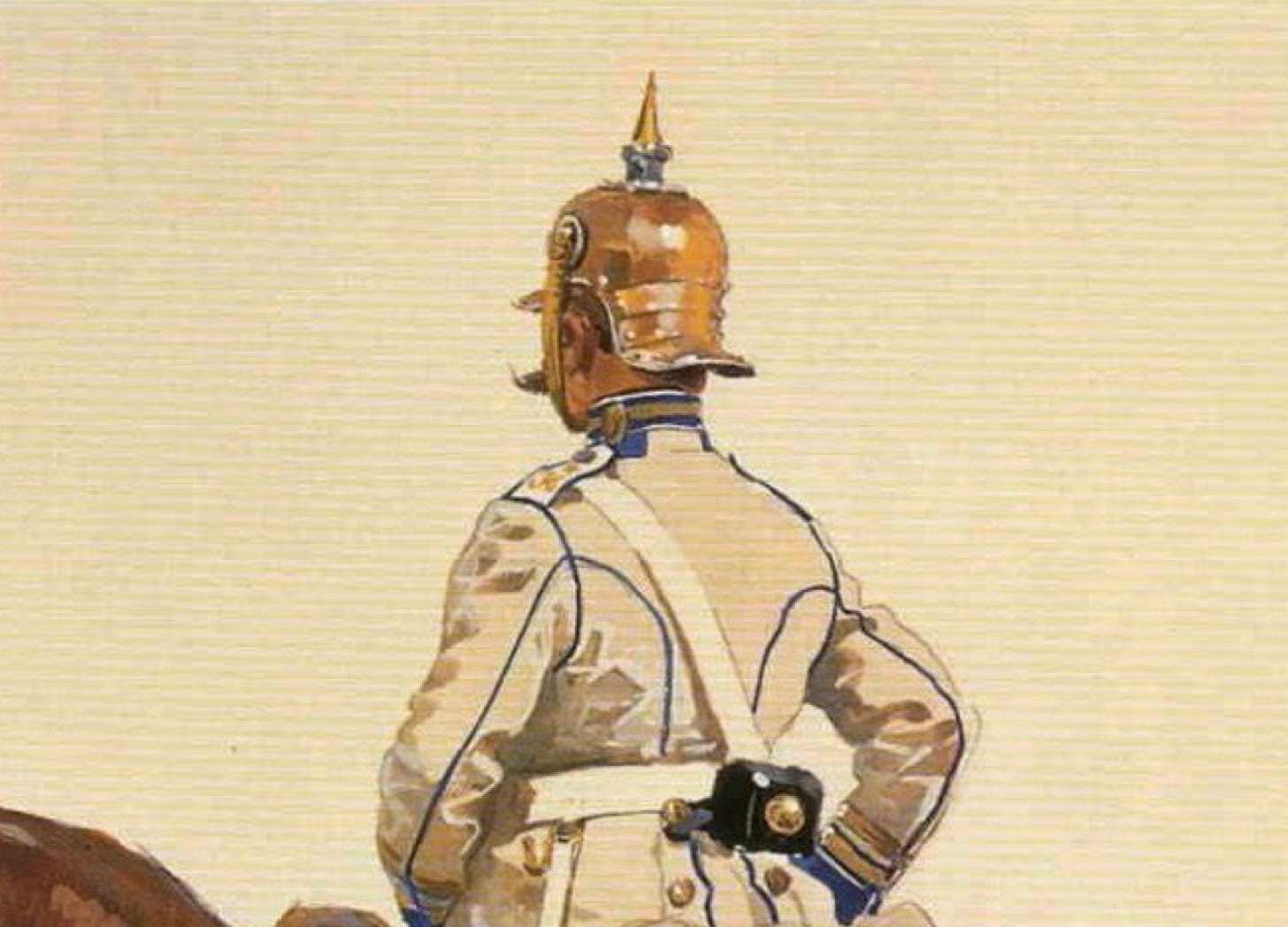

Surrounded by a cloud of medal-wearing generals and wearing his old-style Pickelhaube, the Kaiser walks along our ranks. The golden imperial standard flutters above their heads.

Time and again, the Kaiser greets his soldiers and a sharp, resounding cry can be heard above the sound of the music. Finally, he reaches us, as we stand in the middle of the vast formation.

‘Ninth! Ah … ten … SHUN! Eyes … RIGHT!’

He stands in front of us. We see his familiar face, deeply furrowed and pale, and his gray hair.

“Good morning, Comrades!”

“Good morning, Your Majesty!”

The sky-high cuirassier behind him, wearing an odd-looking helmet with a lobster-tail back-flap, waves the eagle standard.

The Kaiser speaks with General [George] von der Marwitz [commanding general of the Second Army) and our division commander. Then he walks along the front, with his finger touching the brim of his helmet. He moves on to the next detachment.

‘At … EASE!’

‘So that’s him’, my neighbor whispers in the ranks.

Yes, that was him! It was the only time in my life that I saw the Kaiser up close. I had seen him once before, at a big celebration in my home town. But I was a child at the time, and my memories were less than vivid.

‘He doesn’t look very well’, my neighbor says again.

‘It’s no wonder — with the things he’s got to worry about.’

‘I wouldn’t want to be the Kaiser.’

‘I wouldn’t want to be in his shoes either,”

I think of the dirtbag who knocked the Kaiser’s portrait off a wall in Flanders some time ago.

My neighbor continues, ‘they don’t have much left – the French and the English and whatever their allies are called. “We should drive him out, then there would be peace.” That’s what is says on the leaflets they dropped a few days ago. That would suit them perfectly, because they can’t manage it themselves. They must think we’re completely stupid, especially now, when we have the upper hand. We at the front already know it, but the rabble back home puts more faith in our enemies. That’s the Emperor’s weak point, that he doesn’t shut those people up back home, that’s what’s needed …’

‘You, in the ranks, shut your pie holes’, snarls a captain from the right flank.

“That’s how it should be back home, too,” I hiss, and my neighbor grins knowingly.

A creaking, disjointed voice echoes in the silent square.

The Kaiser speaks. We turn our attention towards him.

‘Thank you. Despite the enemy’s advantages in both numbers and matériel, you have repelled the enemy’s attacks, freed up the Eastern Front, forced the Russians to make peace. We need to get through the winter and then, next year, achieve decisive victory in the West. The folks at home are making more weapons than every before. With a clenched fist, we will compel the enemy to make peace. This coming Christmas will be the last one of the war. You will spend the following Christmas with your loved ones, at home and in peace.’

‘In company front … parade … March!’

The drums roll. The fifes play a cheerful tune. The shining trumpets ring out. We wait until, at last, we hear the command ‘forward … MARCH!’

Once again, we see the Kaiser, lost in thought, staring at the rows of kicking legs, spraying dirt from the clods of earth in their path. Then we head off to the next event. The parade has ended.

Sources

The text translates, verbatim, a passage from the memoir of Hans Zöberlein Glaube an Deutschland (Belief in Germany) (Munich: Franz Eher, 1943) pages 419-421

Along with lots of other paintings by Carl Becker, the illustration that shows a cuirassier wearing a lobster-tail helmet can be found in Charles Wooley The Kaiser’s Army in Color (Atglen: Schiffer, 2000) (Publisher’s Catalog)

The photo at the top of this page, which shows General von der Marwitz in conversation with the Kaiser, may well capture scenes from the event described in the passage. The film footage, which I found at the US National Archives, seems to show another visit of the same kind.