During the First World War, the Royal Garrison Artillery handled both the heaviest ordnance in the arsenal of the British Empire and the lightest pieces in that inventory. In the following excerpt from his thinly disguised memoir, Brigadier-General Williamson Oswald, who saw much active service while assigned to mountain batteries, recounts two encounters with the paragon of the latter class.1

The scene of the effort to obtain good and new mountain artillery guns now changes to Palestine. The XXI. Corps are struggling for Jerusalem; the time is near the end of November, 1917.

Oswald is acting as Brigadier-General, commanding the Royal Artillery of the Corps. He meets a friend near Kuryat-el-Enab, in the Judean Hills, a Sabbath day’s journey from Jerusalem, as the New Testament says; this is [Major] A. [M.] Colville, his old subaltern of 6 (Jacobs) Mountain Battery.

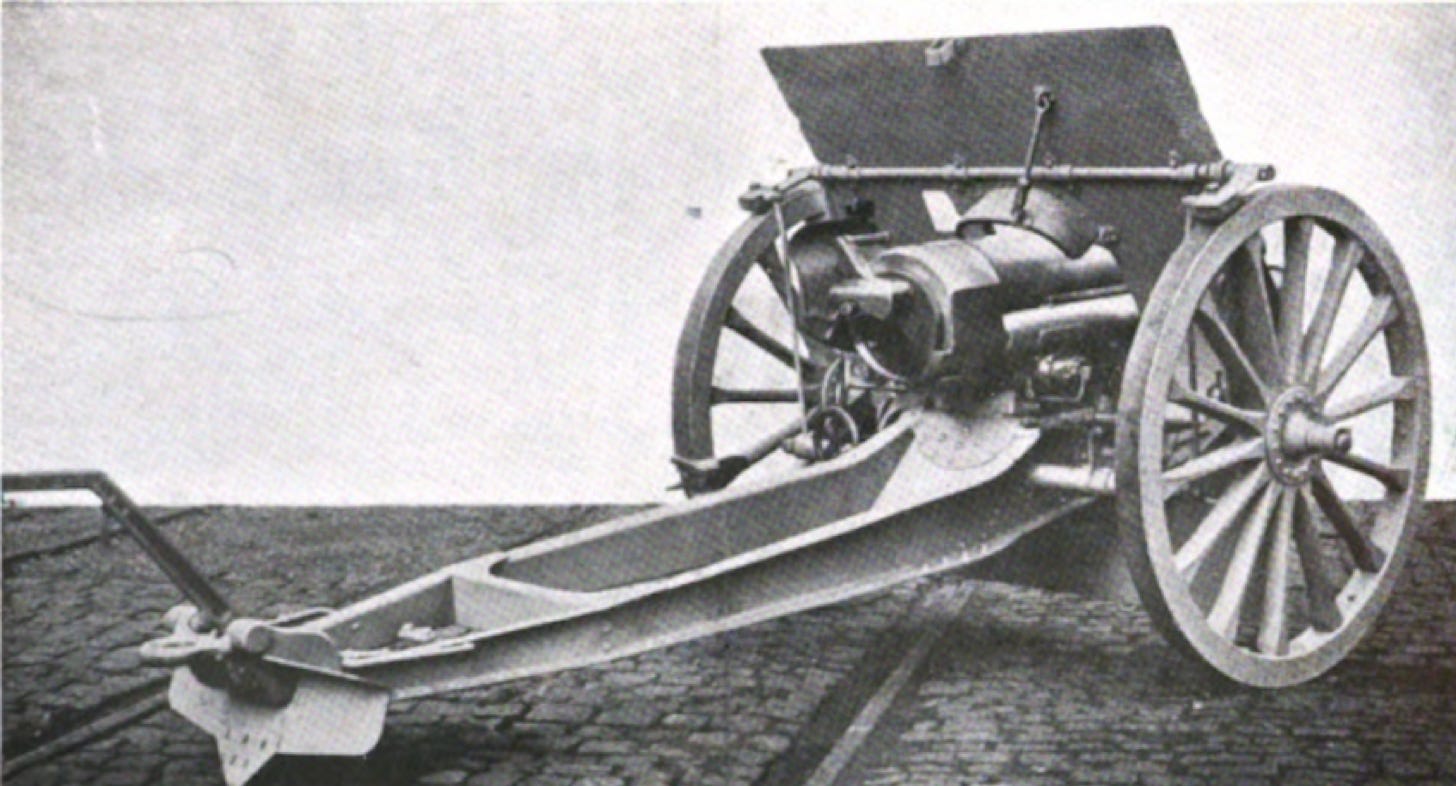

Colville is commanding a battery equipped with a weapon that has not yet fired in anger, but is to do great work in the struggle for Jerusalem, and to fire a hitherto unheard of shell both here and in many a fight up to the day of writing these words. This weapon is the 3.7-inch Mountain Howitzer, quick-firing, shielded, and firing a 20-pound shell loaded with high explosive to a range of 6,000 yards, or 3 1/2 miles.

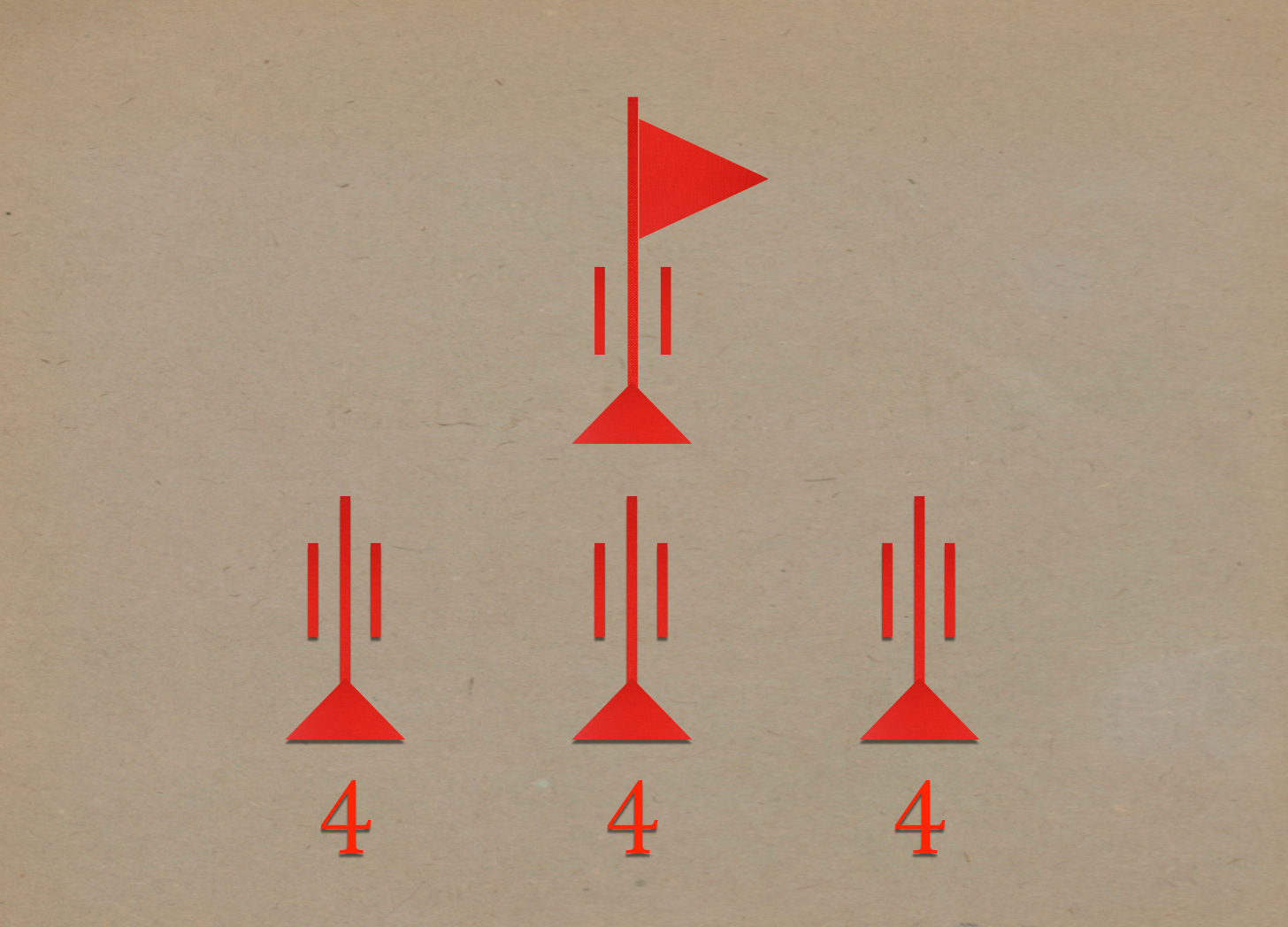

A Brigade [of Mountain Artillery] under [Lieutenant-Colonel Osborne Kendall] Tancock of three batteries or twelve howitzers is destined to help in the taking of Jerusalem, and ultimately the Turkish defeat of 1918, with its results which were, it is conjectured, felt on all fronts.

Oswald was very well pleased to meet these batteries, as their fire was going to reinforce the 18-pounder field guns round Nebi Samwill at the tomb of the Prophet Samuel, where the 52nd and 75th Divisions were having a bloody struggle for the crests of the Judean ridges north of Jerusalem.

Besides having a shell two pounds heavier than [that of] the 18-pounder [field gun], from the very construction of the equipment the mountain guns could be carried practically anywhere a man could climb, and as howitzers could squat behind any hill.

They were most powerful reinforcements in the fight, which subsequent reports showed was much helped by them. They gained a good name for both power and accuracy; also they were able to dispense with roads, and were in consequence popular with Australians, who later on were working in the country east of Jerusalem.

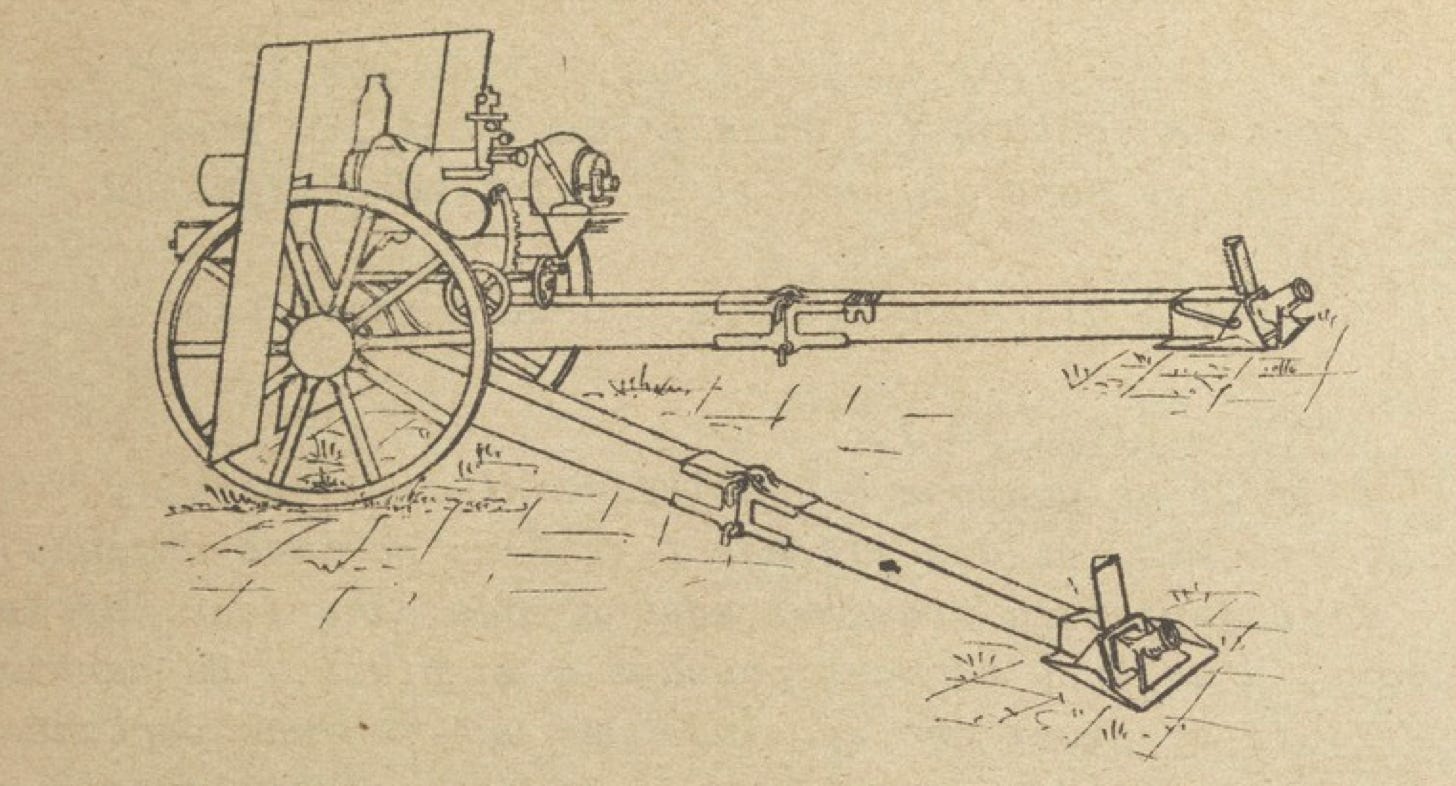

Oswald had another reason for pleasure in seeing these weapons used on a battle front. In 1909, when first he went on the Artillery Committee, these howitzers existed on paper and one had been made as an experiment. In its shooting trials, it showed exceptional accuracy for a howitzer, and its range of 6,000 yards was lengthy and reliable for so small a weapon. It was in two parts, which locked together with a quarter turn of a screw. All its equipment was experimental and fairly satisfactory, but its carriage was heavy and yet somewhat light for its work.

Oswald was prepared to accept this unsatisfactory carriage for the reasons that have been set forth previously as regards the immediate acceptance of the 2.75-inch mountain gun: that once a gun is in the service its minor defects will be eliminated by those who have to use it, provided the defects were minor. But in the case of this 3.7-inch howitzer, the carriage could not be called a minor defect. It was a serious one, and one which in experiment at Shoeburyness in 1911 or 1912 had a bad failure.

This failure came about rather as a surprise. Oswald had asked that the trail or ground end of the carriage should be rested against rock, instead of earth, a circumstance that happens in mountainous and other places, and is unavoidable for a mountain gun.

The gun was fired in this position, and its happened that the muzzle was raised - or elevated, as it is called - to such a height that the breech was lowered to a corresponding position. This position by a curious chance caused an important portion of the breech to be in line with a projection at the back end of the trail.2

The extra bit the gun recoiled or went back in its carriage, due to being against rock and not earth, made the breech hit the trail sufficiently hard to seriously damage the machinery and make repair necessary. This chance accident was fortunate; as Oswald said, ‘the luck of the British Army is to discover things in time.’

It was, however, obvious that the carriage as it stood would not do. The necessity for a series of further changes in the carriage was obvious, and the question was put to Oswald, as Associate Member for Mountain Artillery on the Artillery Committee, whether it was worth while to go on with the 3.7-inch howitzer at all. Oswald strongly advised going on, as the gun portion was so accurate in its shooting powers, and as it was not be expected that the 2.75 gun firing its 10-pounder shells was likely to remain a suitable weapon for ever.

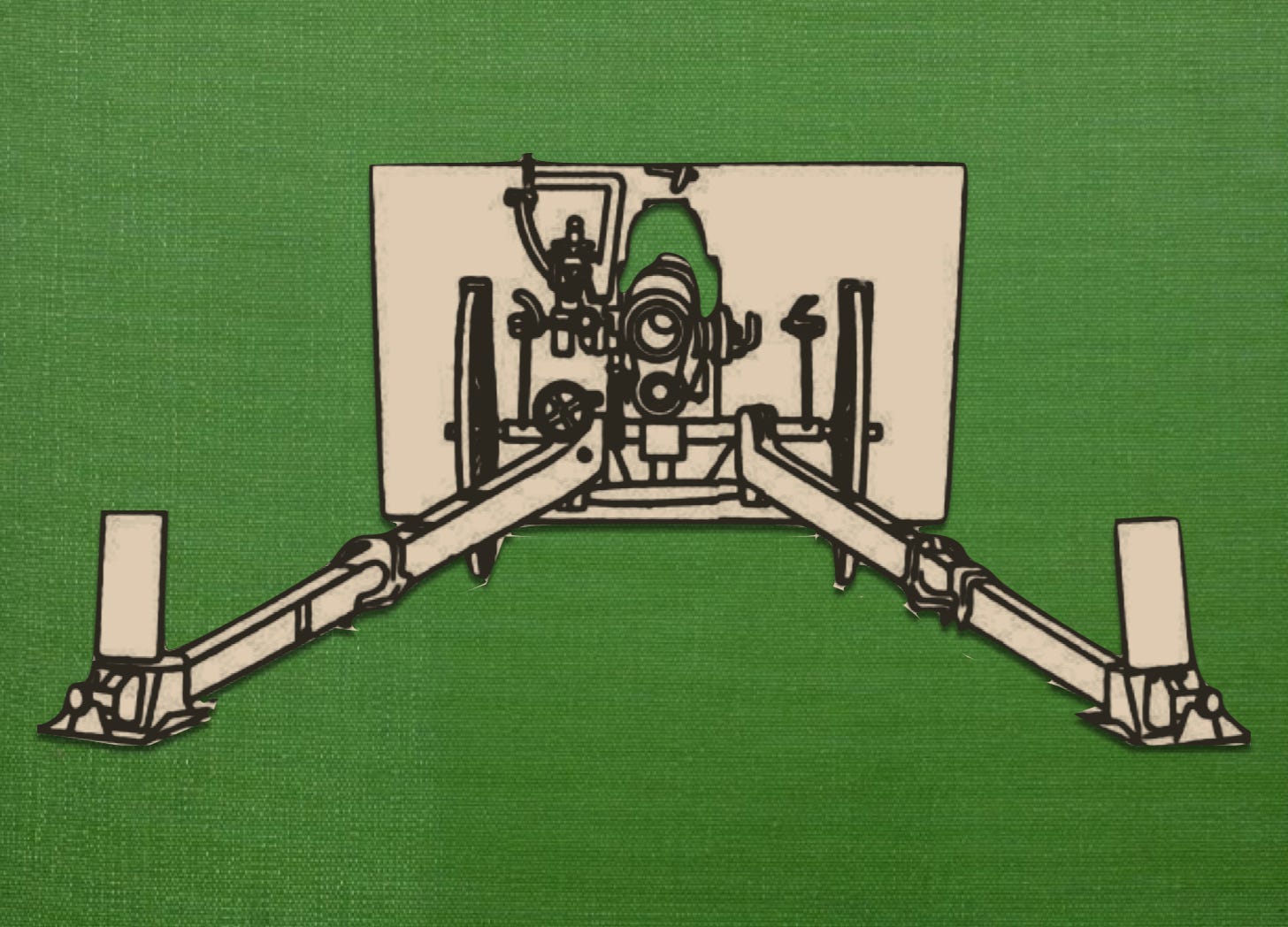

The result was a drastic change in the make and pattern of the gun carriage, which was split down the middle. This allowed the two pieces of the trail or hind supports to be placed as separate supports, which jointly supported the gun when fired, while permitting it - the gun part - to come back safely on firing between the two pieces of the trail.

A most convenient carriage resulted, which allowed fire to be brought to bear to a considerable extent to right and to left without moving the carriage round. This convenience, together with a very good shooting gun, made the 3.7-inch howitzer a weapon well in keeping with the desires of the mountain artillery up to even 1920. Oswald had in consequence some reason to be pleased on that day in 1917 when he first saw the 3.7-inch howitzer going into battle near Jerusalem.

Source for the Text

Oswald Charles Williamson Oswald 61, How Some Wheels Went Round: The 61st Heavy Artillery Group in the Great War. (London: Henry J. Drane, 1929) pages 95-99

Other Sources Consulted

C.A.L. Graham The History of the Indian Mountain Artillery (Aldershot: Gale and Polden, 1957)

Henry Arthur Bethell Modern Guns and Gunnery (Woolwich: Cattermole, 1910)

For Further Reading:

Like BH Liddell Hart, O.C. Williamson Oswald bore a two-barreled surname. While a few official publications place a hyphen between the two elements of this appellation, most omit it. The first given name of this gunner, moreover, duplicated the second element of his family name. Thus, the double appearance of ‘Oswald’ in the full name of our author cannot be blamed on a typographical error.

Though I have yet to find a photo, let alone a technical description, of the prototype described in this passage, I suspect that it possessed a box trail of a type used with many quick-firing howitzers developed in the first decade of the twentieth century.

This 3.7” QF may still be in service by Nepal.

“The extra bit the gun recoiled or went back in its carriage, due to being against rock and not earth, made the breech hit the trail sufficiently hard to seriously damage the machinery and make repair necessary. This chance accident was fortunate; as Oswald said, ‘the luck of the British Army is to discover things in time.’”

Using failure as an impetus to fix and improve. Makes me think of Sam Alaimo article about the use of failure. substack.com/@whatthen/p-149972967